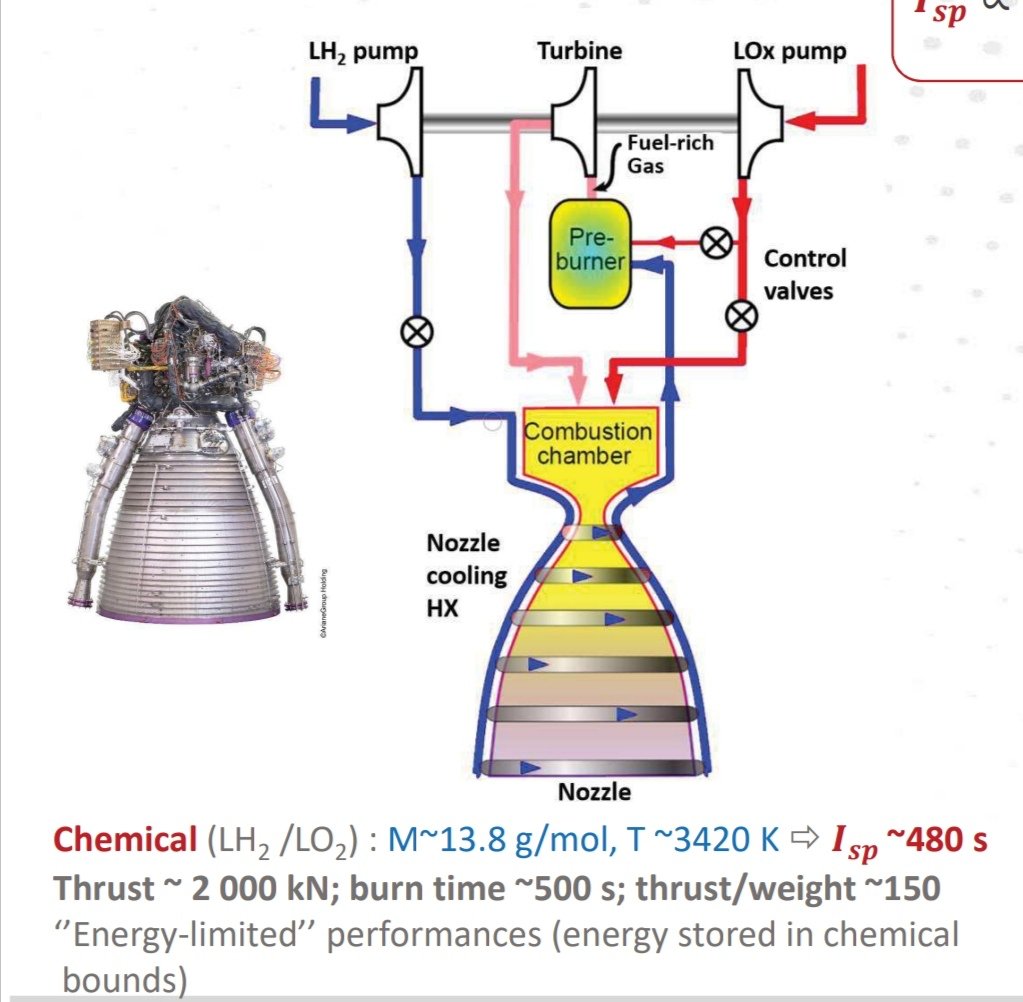

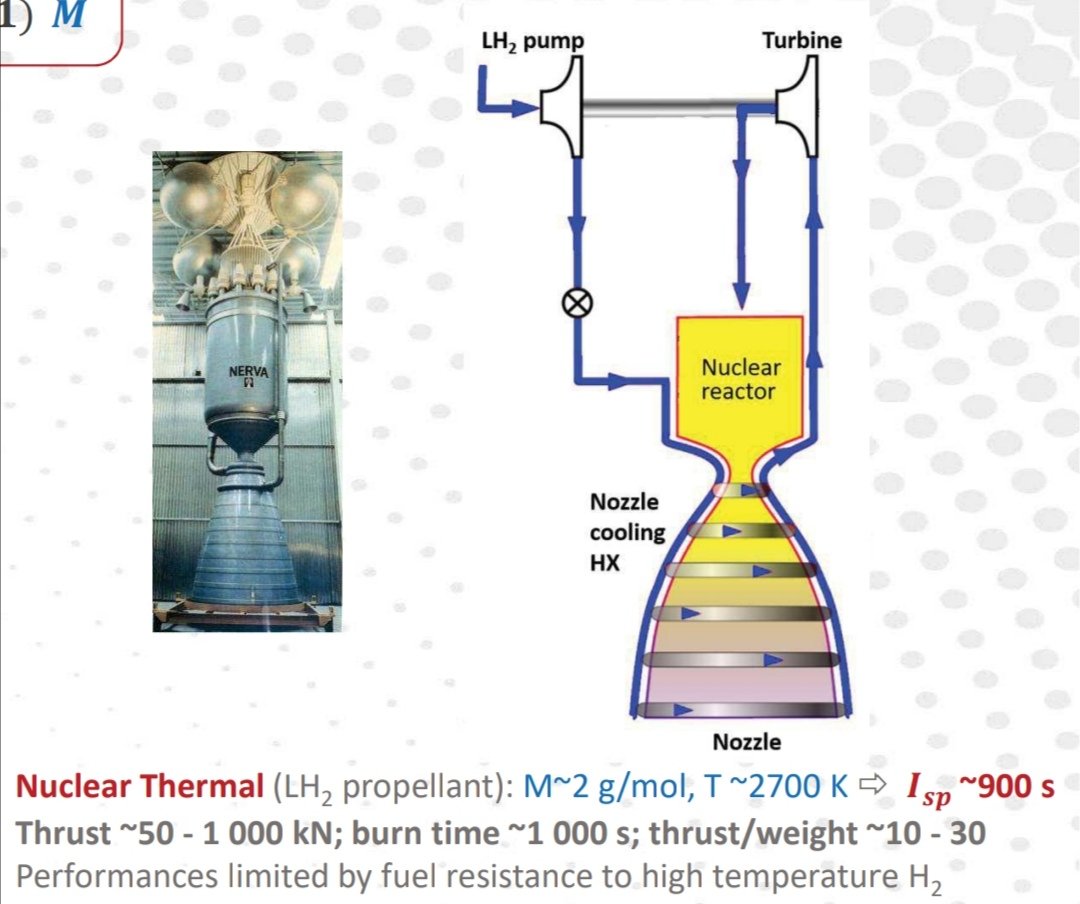

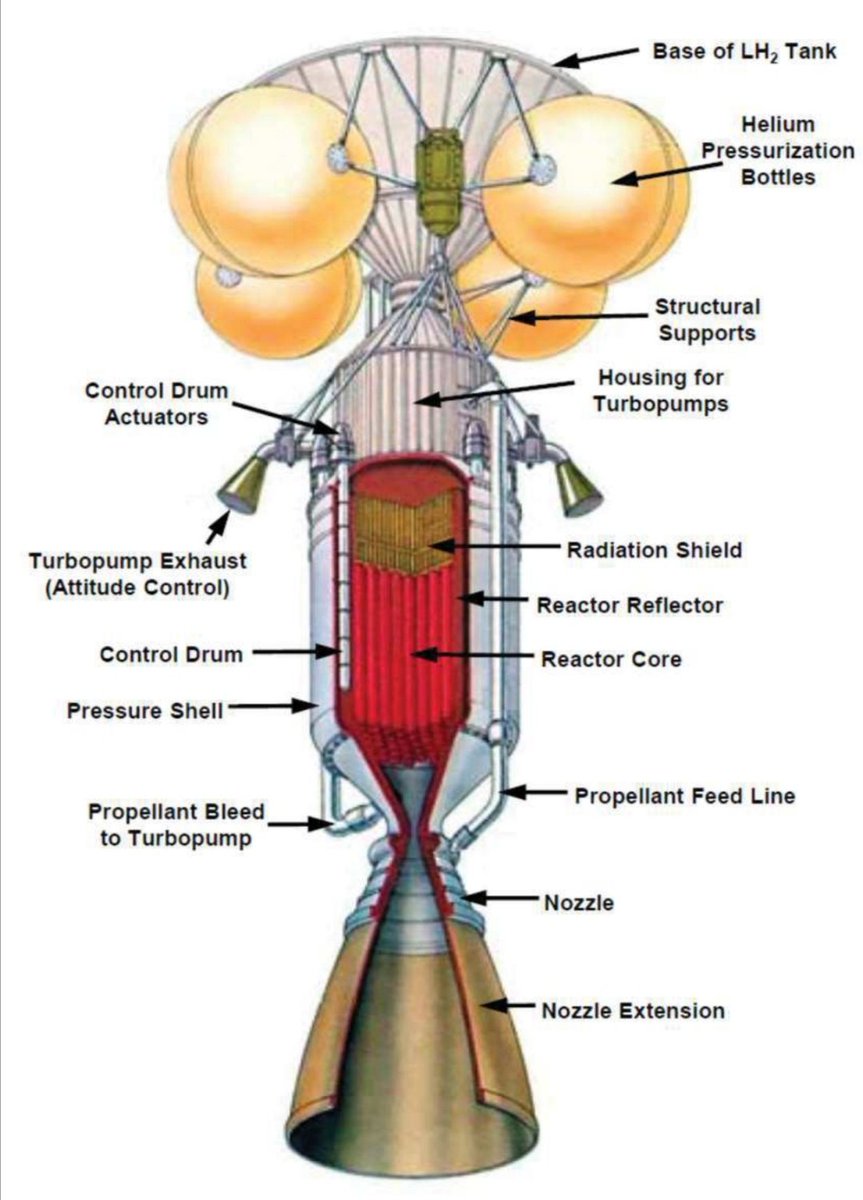

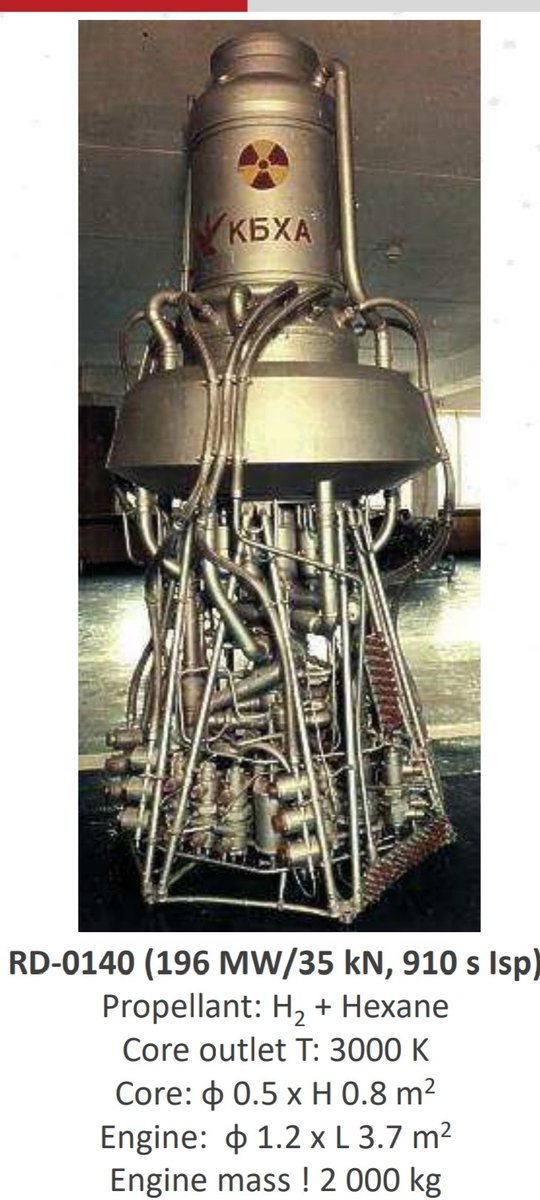

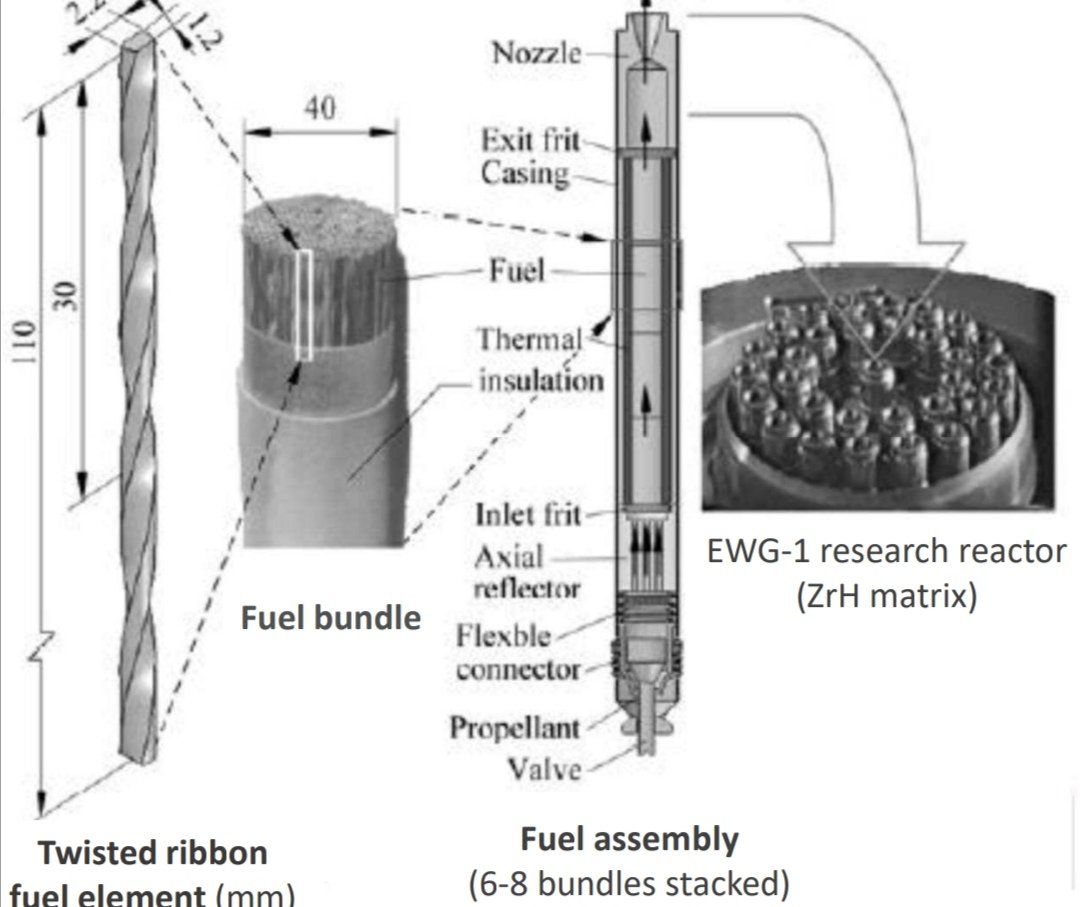

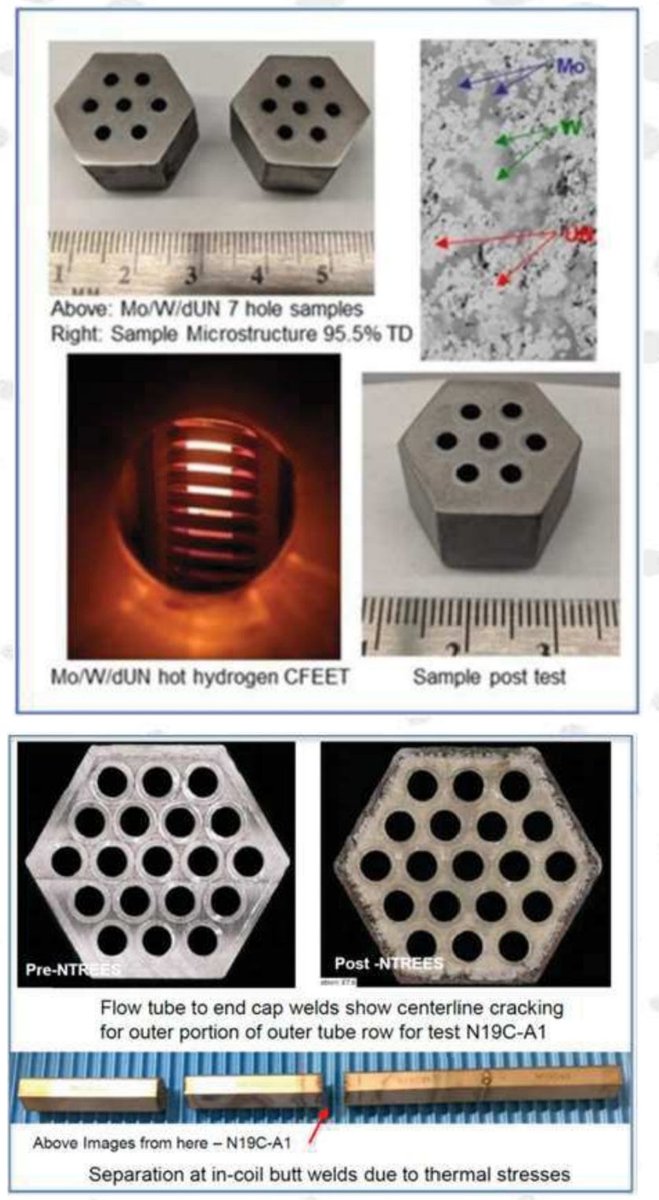

Thirdly, temperature: Chemical combustion reaches max temperatures away from the walls of the combustor (see aerospace combustion thread below) so it can run hotter. In an NTR, the fuel bundle itself is the hottest bit.

Loading suggestions...