Xenophon’s Anabasis: The legend of the 10.000

Is the cure to male loneliness an expedition deep into Asia with your 10.000 merc buddies to kill some barbarians and get paid for it? You’re GODDAMNED RIGHT IT IS! This is the story of an army of Greek super-chads who F**ed around and found out that you must ALWAYS read the fine print in your contract, especially if it’s about going to war, in a foreign land, to fight for a foreign dude against his brother, with their foreign armies (you can replace the “foreign” part with “barbarian” if you wanna be 100% lore-accurate).

On a more serious note, I always found this story extremely moving, on a personal level, even though we are talking about an army of dogs of war; Jocko Willink, and I, agree on the fact that War is a catalyst: it brings out the very worst and the very best in people. And this story is a crazy saga of war, camaraderie, brotherhood, betrayal, broken dreams and lost lives; an army that won all its battles, lost the war but still won the ultimate victory: the one of getting home alive. As someone who has served in Special Forces, I’ve felt the strong bond created among soldiers going through extreme hardships and I can only imagine the pain, suffering and emotions of those fellow-soldiers, despite the thousands of years that separate us. Follow me on this journey, narrated by the very man who took command of that army and lived to tell us the story: Xenophon of Athens.

Xenophon wrote multiple books to narrate the events but I’ll separate the journey in just 5 parts, using the protagonists as the main point of reference for each phase. It’s a huge story and I suggest to secure some peace and quiet to enjoy it; you can even bookmark it and break it in pieces if you prefer it so. I’ll talk to you about some men who no one can deny they were extremely badass and the epitome of a Warrior: Cyrus the Younger (the Persian), Clearchus (the Spartan) and Xenophon (the Athenian).

Is the cure to male loneliness an expedition deep into Asia with your 10.000 merc buddies to kill some barbarians and get paid for it? You’re GODDAMNED RIGHT IT IS! This is the story of an army of Greek super-chads who F**ed around and found out that you must ALWAYS read the fine print in your contract, especially if it’s about going to war, in a foreign land, to fight for a foreign dude against his brother, with their foreign armies (you can replace the “foreign” part with “barbarian” if you wanna be 100% lore-accurate).

On a more serious note, I always found this story extremely moving, on a personal level, even though we are talking about an army of dogs of war; Jocko Willink, and I, agree on the fact that War is a catalyst: it brings out the very worst and the very best in people. And this story is a crazy saga of war, camaraderie, brotherhood, betrayal, broken dreams and lost lives; an army that won all its battles, lost the war but still won the ultimate victory: the one of getting home alive. As someone who has served in Special Forces, I’ve felt the strong bond created among soldiers going through extreme hardships and I can only imagine the pain, suffering and emotions of those fellow-soldiers, despite the thousands of years that separate us. Follow me on this journey, narrated by the very man who took command of that army and lived to tell us the story: Xenophon of Athens.

Xenophon wrote multiple books to narrate the events but I’ll separate the journey in just 5 parts, using the protagonists as the main point of reference for each phase. It’s a huge story and I suggest to secure some peace and quiet to enjoy it; you can even bookmark it and break it in pieces if you prefer it so. I’ll talk to you about some men who no one can deny they were extremely badass and the epitome of a Warrior: Cyrus the Younger (the Persian), Clearchus (the Spartan) and Xenophon (the Athenian).

A world of Change & Chaos

The world was a very unstable and probably chaotic place; and Chaos is good for some lines of business, like mercenary work. The Greeks (or Hellenes as they call themselves) were with no doubt the best warriors the world had ever seen up until that point; their martial prowess (no doubt about that, since their favorite sport was killing each other) was undeniable, their technology (battle gear and alloys) superior and discipline (only during battle – keep that in mind) unquestionable. So, they used to sell their services to other regional powers when they were not busy killing each other or defending the nation; they sent mercenary armies to Egypt and Persia on an almost regular basis.

The epic tale of the “Ten Thousand” (or Myrioi – the Greek word for 10.000) begins around 401 BCE; Greece was just beginning to heal its wounds from the long and devastating Peloponnesian Civil War between Sparta and Athens (and all smaller cities that allied with them). Keep in mind that this was the war that ended the supremacy of Athens and Sparta within the Greek world and allowed for Macedonia (and later Epirus) to assume the leadership among the Greeks. Around the time when the Greek world was ending this bloody struggle, another one was about to begin in the East.

Following the death of king Darius II in 404 BCE, the Persian throne passed to his older son Artaxerxes II. However, his brother, Cyrus the Younger, also coveted the crown. The suspicion and distrust between the two started boiling and Cyrus began secretly building an army to overthrow his brother. He was smart enough to acknowledge that his power (and forces) was insufficient to confront the vast numbers the King could field, so he sent out his advisors to seek and enlist a superweapon: an army of Super-Chads, so badass that even their reputation would make any enemy tremble: the Greeks. Despite centuries of animosity and existential struggle between the Persians and the Greeks, Cyrus acknowledged the discipline and bravery of the battle-hardened Greek hoplites; so, he started with recruiting one tough son of a b*tch and then more than 10.000 followed.

The world was a very unstable and probably chaotic place; and Chaos is good for some lines of business, like mercenary work. The Greeks (or Hellenes as they call themselves) were with no doubt the best warriors the world had ever seen up until that point; their martial prowess (no doubt about that, since their favorite sport was killing each other) was undeniable, their technology (battle gear and alloys) superior and discipline (only during battle – keep that in mind) unquestionable. So, they used to sell their services to other regional powers when they were not busy killing each other or defending the nation; they sent mercenary armies to Egypt and Persia on an almost regular basis.

The epic tale of the “Ten Thousand” (or Myrioi – the Greek word for 10.000) begins around 401 BCE; Greece was just beginning to heal its wounds from the long and devastating Peloponnesian Civil War between Sparta and Athens (and all smaller cities that allied with them). Keep in mind that this was the war that ended the supremacy of Athens and Sparta within the Greek world and allowed for Macedonia (and later Epirus) to assume the leadership among the Greeks. Around the time when the Greek world was ending this bloody struggle, another one was about to begin in the East.

Following the death of king Darius II in 404 BCE, the Persian throne passed to his older son Artaxerxes II. However, his brother, Cyrus the Younger, also coveted the crown. The suspicion and distrust between the two started boiling and Cyrus began secretly building an army to overthrow his brother. He was smart enough to acknowledge that his power (and forces) was insufficient to confront the vast numbers the King could field, so he sent out his advisors to seek and enlist a superweapon: an army of Super-Chads, so badass that even their reputation would make any enemy tremble: the Greeks. Despite centuries of animosity and existential struggle between the Persians and the Greeks, Cyrus acknowledged the discipline and bravery of the battle-hardened Greek hoplites; so, he started with recruiting one tough son of a b*tch and then more than 10.000 followed.

Cyrus the Younger: the fratricide

It is said that Cyrus was the best one of the two brothers: noble, brave, battle hardened, generous, just and eloquent. Yet, he was the younger (pun intended) and therefore his older brother was next in line. He maintained an admiration of the Greek civilization and was even heard saying that he would like them with him, as allies, not only for their martial superiority but also the intellectual one; yet, being very eloquent himself when talking to Greeks to convince them, and our narrator being a Greek himself, it is kind of expected for Cyrus to be portrayed positively and as an admirer of the Greek “chadness”. But honestly, his actions – and not so much Xenophon’s words – prove the merit of these descriptions of Cyrus as you will see very soon.

Naturally, there was a total lack of trust between the two Persian Princes, for good reason, and they both watched each other’s moves very carefully; this is exactly why Cyrus, a satrap-Prince now, started recruiting and building an army in secrecy. The pretext was that he was trying to handle business within his region, dealing with unruly tribes; keep in mind that even if Persia was a powerful empire covering immense stretches of land, there were multiple nations and tribes within those stretches that were nominally submitting to the Great King of Kings (LOL, Leonidas, the Spartan, would beg to differ) or straight out ignoring Persian rule. This was a good pretext for Cyrus early on, while he gathered his own army and allied satraps.

It is important to note, that he lured the Greeks with promises of “easy work”, promising them that he needed their help only to subdue local tribes, namely the Pisidians, not fight the King; that’s part of why he tried to rush their coming, asking for forced marches, in order to surprise his brother before the latter could anticipate it.

It is said that Cyrus was the best one of the two brothers: noble, brave, battle hardened, generous, just and eloquent. Yet, he was the younger (pun intended) and therefore his older brother was next in line. He maintained an admiration of the Greek civilization and was even heard saying that he would like them with him, as allies, not only for their martial superiority but also the intellectual one; yet, being very eloquent himself when talking to Greeks to convince them, and our narrator being a Greek himself, it is kind of expected for Cyrus to be portrayed positively and as an admirer of the Greek “chadness”. But honestly, his actions – and not so much Xenophon’s words – prove the merit of these descriptions of Cyrus as you will see very soon.

Naturally, there was a total lack of trust between the two Persian Princes, for good reason, and they both watched each other’s moves very carefully; this is exactly why Cyrus, a satrap-Prince now, started recruiting and building an army in secrecy. The pretext was that he was trying to handle business within his region, dealing with unruly tribes; keep in mind that even if Persia was a powerful empire covering immense stretches of land, there were multiple nations and tribes within those stretches that were nominally submitting to the Great King of Kings (LOL, Leonidas, the Spartan, would beg to differ) or straight out ignoring Persian rule. This was a good pretext for Cyrus early on, while he gathered his own army and allied satraps.

It is important to note, that he lured the Greeks with promises of “easy work”, promising them that he needed their help only to subdue local tribes, namely the Pisidians, not fight the King; that’s part of why he tried to rush their coming, asking for forced marches, in order to surprise his brother before the latter could anticipate it.

Clearchus: Spartan Plus Super-Chad

I hope you do remember my mention of the first tough son of a b*tch that this whole thing started with; he was Clearchus, a Spartan general so badass and cunning, that even the other Spartans could not handle. It is said that they sent him initially, as a general, with a Spartan detachment in Thrace to take over Byzantium (ring any bells? Yes, Byzantium, after which the later Byzantine Empire was named, was an ancient Greek colony); after kinda completing the mission, our boy took the liberty of striking deals, changing the narrative and generally engaging in.. entrepreneurial activities and side quests; Spartans, being Spartans, got quickly fed up with his sh*t and recalled him to report back and get punished. A true Spartan, always putting the interests of the city above his own, would have returned indeed but our boy was the enhanced edition: a Spartan with his own mind (Spartan +, limited edition); so he just said “No f*cking way” and went AWOL. News about a renegade Spartan army with freelance options soon reached the ears of Cyrus and he promptly sent envoys to Clearchus, with a hefty amount of money, to invite him over; it is not clear at this point if he did share the true purpose of the expedition with Clearchus or just talked about an easy mission against the Pisidian tribes. Either way, news about “easy money” spread across Greece and soon bands of freelancing hoplites from all cities started gathering on the coast of Asia Minor (where the Greek Ionian cities were). The army gathered numbered more than 10.000 men and consisted of separate bands with their city of origin being the sorting factor; several captains, through an informal council (since Greeks need to be talking EVERYTHING over), led the army with the most prevalent ones (due to their origin and reputation) being Clearhus and Cheirisofus from Sparta and Proxenos of Boiotia (who invited young Xenophon as a friend and guest on this journey), among others. Since Cyrus was in a rush, he urged the Greeks to move fast and meet him so they could together “attack the Pisidians”. It was not a peaceful journey or an easy one; think about marching more than 2000 miles into Asia, through plains, deserts and mountains; the army was plagued by in-fighting, desertions, and constant supply challenges. But they did make it through Anatolia and reached Babylonia. At this point, it wasn’t too hard for Artaxerxes, the king, to figure out that Cyrus didn’t call 10.000 Greek dudes to subdue “a local barbarian tribe” and started preparing for battle; It was on.

Meanwhile, the Greek boys started also figuring it out and since they do talk about everything started pushing back on Clearchus. Keep in mind, that is a key characteristic of Greeks and their armies from ancient times until today; they did have immense courage and discipline on the battlefield but they did not obey hierarchy in the strict fashion Romans or modern armies understand it; they needed to be convinced. Indicatively, from the Troyan War even to Alexander’s campaign, we see Greeks having councils and commanders putting things for vote, or simple soldiers being invited to share their opinions as equals. Therefore, you might understand why they fought like beasts (because they believed in the cause) but also why they love fighting each other so much (because they don’t believe in each other many times). So you can imagine leading 10.000 Greeks (with approximately 100 opinions each) in a forced march through deserts to fight; it can be kinda tiring. Either way, they started talking about it and at some point, Cyrus was brought to talk openly to all the Greek captains and explain that there was a “fine print” in the “contract”; of course, they gave 0 Fs and started saying they didn’t sign up for this shit. He sweettalked them, he ass-kissed them and generally promised them everything in order to make them stay; so what did our boys do? They thought: “since we did walk this far” and “since we can beat barbarian ass all day” and “since having the Persian king as a friend could be nice” they demanded a hefty salary increase and sealed the new deal with a handshake. It was on, indeed, and our boys were in for a treat.

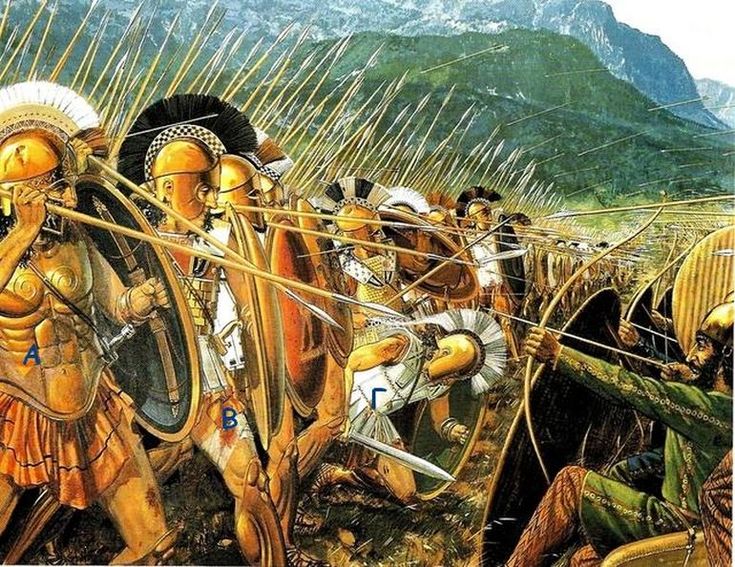

Everybody was super happy and started marching to meet the King’s army; Cyrus was so proud of his new army that he started exhibiting them to his friends and potential allies as a flex. Indicatively, he called some of his Persian allies and organized an exhibition of his army; he arranged for the Greeks to form as a phalanx on one side and all the rest of his Persian army on the other side opposing them; Clearchus and the boys, being super-chads, wanted to pull a little prank; so while Cyrus and his friends were talking they start hearing a deep hum: those weirdos, the Greeks started chanting their War-song (paian) and marching without an order towards the barbarian side. “Ok, nice one, but stop it” Cyrus and the Persians probably thought; but the Greeks didn’t stop, the phalanx actually started running with bronze helmets, breastplates, and bronze leg greaves, in a shoulder-to-shoulder formation with their spears and bronze shields in close formation blinding their counterparts and deafening them with their battle cry The Persians quickly crapped their pants, broke formation and started running back to their camp (have you seen the “300”? imagine this thing coming against you).. The Greeks stopped and broke formations laughing out loud; our super chads made their point and Cyrus was convinced the Throne was his.

The day of the battle came and the two armies met at Cunaxa; Cyrus and the Greeks faced Artaxerxes. The numbers vary according to the source; having read the original books, Xenophon talks about tens of thousands for the Persian army (probably around 50 thousand men), while Cyrus probably fielded our boys under Clearchus on the right and another equivalent force of Persians under Arieus (a Persian satrap) on the left, while he held the center with his 600 elite royal guard of horsemen. Artaxerxes’ army appeared around afternoon, lifting an enormous dust cloud that was stirred by the ceaseless tramp of thousands of feet. Occasionally, the choking swirls parted to reveal the sun-glinting tips of bronze spearheads. It was a spectacle that could chill the blood even in the torrid afternoon heat. Cyrus surveyed his army and heard again that familiar sound he heard back in the exhibition for the first time; he asked Xenophon, a low ranked captain at that point, to explain what the weirdos were chanting; “Zeus soter” (Zeus, savior) and “Nike” (Rings any bell? Yes, it means victory in Greek). His chad army was ready to kick ass; he gave instructions to Clearchus to attack the enemy center (where his brother would be). And the Greeks obeyed, as loyal subjects, destroyed the enemy, killed the King and everybody lived happily ever after. F*CK NO bro! Who the F did Cyrus think he was? Telling a Spartan what to do? And then what? Punch Zeus too?! Our boy, Clearchus, replied laconically (pun intended) something along the lines of “I got you, fam” and decided anyway do his own thing and attack directly to the opposite side (Artaxerxes’s left wing) having Cyrus on their left and Euprates (the river) on their right, to avoid being outflanked by cavalry.

When the opposing armies were no more than 500 yards apart, the Greeks began to advance with their crazy songs and battle cries in full swing. Each man carried a large shield on his left arm, while his right brandished an iron-tipped spear (hoplon, weapon in Greek). The aligned ranks moved with perfect precision, colorful horsehair plumes nodding over burnished bronze helmets in cadence with every step. They were an impenetrable wall of flesh, bronze, balls of steel and super-chad attitude; they stormed the enemy lines (who vastly outnumbered them) and massacred them, causing total collapse of the enemy left wing. Meanwhile, our boy Cyrus, (realizing that he did not have a big d*ck enough energy to manage the Greek maniacs) rushed bravely with his personal guard against his brother’s royal guard, to cover the Greek flanks (like they needed it, LOL!) and kill his brother; he wanted to personally kill him so noone could dispute him after. So just to recap how the battle developed, the Greeks on the right attacked directly the enemy left wing, and Cyrus attacked directly the enemy center; his left wing stayed behind. The two royal guards clashed extremely hard and in the midst of battle the brothers got close; Cyrus threw his spear against Artaxerxes and mortally wounded him in the chest but his joy was short-lived. Another spear got him in the eye, dropping him dead on the spot. Arieus, that coward satrap on the left wing, did not even engage and run when he saw the scene. Once Cyrus was dead, the “rebel” Persians broke and run, while the loyalists pursued them and moved to pillage the enemy camps, including the Greek one.

Meanwhile, our Greek boys, having massacred the enemy flank and after pursuing them for miles, turned back and saw more Persians on the battlefield waiting them in battle formation; I mean, who can tell one barbarian from another, right? They rushed again and drove those back as well. They won two great victories and now they remained in the area to rest and regroup with Cyrus; but Cyrus was nowhere to be found and their camp was pillaged.

They actually found out the next day when a messenger from Arieus (that coward satrap) brought the news; the news devastated them: even though they won two victories that day, the war was lost; their money was gone, their allies deserted them and they were in the middle of fricking nowhere. The day grew hot, and though the troops could quench their thirst in the Euphrates, food was scarce and the stench from the dead bodies was poisoning the air; negotiations with the King started soon after, as he could not beat them in battle but did not want such a powerful force within his kingdom. He demanded their complete surrender (LOL, and then what? Slap Ares too in the face?) and they promptly rejected it, stating that if they were not allowed to leave, they would destroy Persia (also LOL); but they were also desperate as well. They even offered Arieus to help him get the throne but he also refused, as he lacked support among the Persians; a loyalist satrap, Tissafernes, resumed negotiations with Clearchus. They agreed on a truce and he offered the Greeks supplies promising to escort them back home; the Greeks resumed their march back, fascinated by the new sights and wonders they encountered on the way back, keeping an eye out for Persian treachery; the crossed the Great Wall of Media, met the Tigris river and found something that could probably look like heaven, after so many weeks in hell: a small town with green trees flourished amid scenes of natural beauty; after many miles of marches, they reached Opis (where Greeks would be found again during Alexander’s campaign) and encountered a large Persian army. Clearchus, being a formidable and cunning general, formed his men in a column only two abreast. The long, snaking line of hoplites seemed two or three times their actual number. The Persians, feeling discretion is the better part of valor, let the Greeks move on without incident. At some point, Clearchus felt confident that the Persians really wanted to help them reach home (as was probably in their best interest) and wanted to squash the beef; he called for a council of the army telling them that he would approach Tissafernes and re-new the truce to improve their relationship; ironically, a young hoplite (a nobody) voiced his concern and distrust of the Persians, with most of the army agreeing. The thick-headed Spartan did not listen and arranged for a dinner with the Persian satrap in their camp; he took with him the army’s most prominent captains: Proxenus, Menon the Thessalian, Agias the Arcadian, and Socrates the Achaean. They were welcomed by the satrap, offered wine and enjoyed the feast until they didn’t; the “Rains of Castamere” music would be a fitting ambient here. The treacherous satrap rounded them up and executed them, hoping that this would break the Greek army and cause their immediate surrender; the army got the news by a soldier, who holding his intestines in his hands after being slashed during the massacre, run the distance from one camp to the other to alert them.. gruesome sight. That evening the Greeks shivered in their cloaks, so depressed that few kindled campfires and fewer still bothered to eat; our boys were left stranded for a second time without a leader and things were looking extremely bad.

I hope you do remember my mention of the first tough son of a b*tch that this whole thing started with; he was Clearchus, a Spartan general so badass and cunning, that even the other Spartans could not handle. It is said that they sent him initially, as a general, with a Spartan detachment in Thrace to take over Byzantium (ring any bells? Yes, Byzantium, after which the later Byzantine Empire was named, was an ancient Greek colony); after kinda completing the mission, our boy took the liberty of striking deals, changing the narrative and generally engaging in.. entrepreneurial activities and side quests; Spartans, being Spartans, got quickly fed up with his sh*t and recalled him to report back and get punished. A true Spartan, always putting the interests of the city above his own, would have returned indeed but our boy was the enhanced edition: a Spartan with his own mind (Spartan +, limited edition); so he just said “No f*cking way” and went AWOL. News about a renegade Spartan army with freelance options soon reached the ears of Cyrus and he promptly sent envoys to Clearchus, with a hefty amount of money, to invite him over; it is not clear at this point if he did share the true purpose of the expedition with Clearchus or just talked about an easy mission against the Pisidian tribes. Either way, news about “easy money” spread across Greece and soon bands of freelancing hoplites from all cities started gathering on the coast of Asia Minor (where the Greek Ionian cities were). The army gathered numbered more than 10.000 men and consisted of separate bands with their city of origin being the sorting factor; several captains, through an informal council (since Greeks need to be talking EVERYTHING over), led the army with the most prevalent ones (due to their origin and reputation) being Clearhus and Cheirisofus from Sparta and Proxenos of Boiotia (who invited young Xenophon as a friend and guest on this journey), among others. Since Cyrus was in a rush, he urged the Greeks to move fast and meet him so they could together “attack the Pisidians”. It was not a peaceful journey or an easy one; think about marching more than 2000 miles into Asia, through plains, deserts and mountains; the army was plagued by in-fighting, desertions, and constant supply challenges. But they did make it through Anatolia and reached Babylonia. At this point, it wasn’t too hard for Artaxerxes, the king, to figure out that Cyrus didn’t call 10.000 Greek dudes to subdue “a local barbarian tribe” and started preparing for battle; It was on.

Meanwhile, the Greek boys started also figuring it out and since they do talk about everything started pushing back on Clearchus. Keep in mind, that is a key characteristic of Greeks and their armies from ancient times until today; they did have immense courage and discipline on the battlefield but they did not obey hierarchy in the strict fashion Romans or modern armies understand it; they needed to be convinced. Indicatively, from the Troyan War even to Alexander’s campaign, we see Greeks having councils and commanders putting things for vote, or simple soldiers being invited to share their opinions as equals. Therefore, you might understand why they fought like beasts (because they believed in the cause) but also why they love fighting each other so much (because they don’t believe in each other many times). So you can imagine leading 10.000 Greeks (with approximately 100 opinions each) in a forced march through deserts to fight; it can be kinda tiring. Either way, they started talking about it and at some point, Cyrus was brought to talk openly to all the Greek captains and explain that there was a “fine print” in the “contract”; of course, they gave 0 Fs and started saying they didn’t sign up for this shit. He sweettalked them, he ass-kissed them and generally promised them everything in order to make them stay; so what did our boys do? They thought: “since we did walk this far” and “since we can beat barbarian ass all day” and “since having the Persian king as a friend could be nice” they demanded a hefty salary increase and sealed the new deal with a handshake. It was on, indeed, and our boys were in for a treat.

Everybody was super happy and started marching to meet the King’s army; Cyrus was so proud of his new army that he started exhibiting them to his friends and potential allies as a flex. Indicatively, he called some of his Persian allies and organized an exhibition of his army; he arranged for the Greeks to form as a phalanx on one side and all the rest of his Persian army on the other side opposing them; Clearchus and the boys, being super-chads, wanted to pull a little prank; so while Cyrus and his friends were talking they start hearing a deep hum: those weirdos, the Greeks started chanting their War-song (paian) and marching without an order towards the barbarian side. “Ok, nice one, but stop it” Cyrus and the Persians probably thought; but the Greeks didn’t stop, the phalanx actually started running with bronze helmets, breastplates, and bronze leg greaves, in a shoulder-to-shoulder formation with their spears and bronze shields in close formation blinding their counterparts and deafening them with their battle cry The Persians quickly crapped their pants, broke formation and started running back to their camp (have you seen the “300”? imagine this thing coming against you).. The Greeks stopped and broke formations laughing out loud; our super chads made their point and Cyrus was convinced the Throne was his.

The day of the battle came and the two armies met at Cunaxa; Cyrus and the Greeks faced Artaxerxes. The numbers vary according to the source; having read the original books, Xenophon talks about tens of thousands for the Persian army (probably around 50 thousand men), while Cyrus probably fielded our boys under Clearchus on the right and another equivalent force of Persians under Arieus (a Persian satrap) on the left, while he held the center with his 600 elite royal guard of horsemen. Artaxerxes’ army appeared around afternoon, lifting an enormous dust cloud that was stirred by the ceaseless tramp of thousands of feet. Occasionally, the choking swirls parted to reveal the sun-glinting tips of bronze spearheads. It was a spectacle that could chill the blood even in the torrid afternoon heat. Cyrus surveyed his army and heard again that familiar sound he heard back in the exhibition for the first time; he asked Xenophon, a low ranked captain at that point, to explain what the weirdos were chanting; “Zeus soter” (Zeus, savior) and “Nike” (Rings any bell? Yes, it means victory in Greek). His chad army was ready to kick ass; he gave instructions to Clearchus to attack the enemy center (where his brother would be). And the Greeks obeyed, as loyal subjects, destroyed the enemy, killed the King and everybody lived happily ever after. F*CK NO bro! Who the F did Cyrus think he was? Telling a Spartan what to do? And then what? Punch Zeus too?! Our boy, Clearchus, replied laconically (pun intended) something along the lines of “I got you, fam” and decided anyway do his own thing and attack directly to the opposite side (Artaxerxes’s left wing) having Cyrus on their left and Euprates (the river) on their right, to avoid being outflanked by cavalry.

When the opposing armies were no more than 500 yards apart, the Greeks began to advance with their crazy songs and battle cries in full swing. Each man carried a large shield on his left arm, while his right brandished an iron-tipped spear (hoplon, weapon in Greek). The aligned ranks moved with perfect precision, colorful horsehair plumes nodding over burnished bronze helmets in cadence with every step. They were an impenetrable wall of flesh, bronze, balls of steel and super-chad attitude; they stormed the enemy lines (who vastly outnumbered them) and massacred them, causing total collapse of the enemy left wing. Meanwhile, our boy Cyrus, (realizing that he did not have a big d*ck enough energy to manage the Greek maniacs) rushed bravely with his personal guard against his brother’s royal guard, to cover the Greek flanks (like they needed it, LOL!) and kill his brother; he wanted to personally kill him so noone could dispute him after. So just to recap how the battle developed, the Greeks on the right attacked directly the enemy left wing, and Cyrus attacked directly the enemy center; his left wing stayed behind. The two royal guards clashed extremely hard and in the midst of battle the brothers got close; Cyrus threw his spear against Artaxerxes and mortally wounded him in the chest but his joy was short-lived. Another spear got him in the eye, dropping him dead on the spot. Arieus, that coward satrap on the left wing, did not even engage and run when he saw the scene. Once Cyrus was dead, the “rebel” Persians broke and run, while the loyalists pursued them and moved to pillage the enemy camps, including the Greek one.

Meanwhile, our Greek boys, having massacred the enemy flank and after pursuing them for miles, turned back and saw more Persians on the battlefield waiting them in battle formation; I mean, who can tell one barbarian from another, right? They rushed again and drove those back as well. They won two great victories and now they remained in the area to rest and regroup with Cyrus; but Cyrus was nowhere to be found and their camp was pillaged.

They actually found out the next day when a messenger from Arieus (that coward satrap) brought the news; the news devastated them: even though they won two victories that day, the war was lost; their money was gone, their allies deserted them and they were in the middle of fricking nowhere. The day grew hot, and though the troops could quench their thirst in the Euphrates, food was scarce and the stench from the dead bodies was poisoning the air; negotiations with the King started soon after, as he could not beat them in battle but did not want such a powerful force within his kingdom. He demanded their complete surrender (LOL, and then what? Slap Ares too in the face?) and they promptly rejected it, stating that if they were not allowed to leave, they would destroy Persia (also LOL); but they were also desperate as well. They even offered Arieus to help him get the throne but he also refused, as he lacked support among the Persians; a loyalist satrap, Tissafernes, resumed negotiations with Clearchus. They agreed on a truce and he offered the Greeks supplies promising to escort them back home; the Greeks resumed their march back, fascinated by the new sights and wonders they encountered on the way back, keeping an eye out for Persian treachery; the crossed the Great Wall of Media, met the Tigris river and found something that could probably look like heaven, after so many weeks in hell: a small town with green trees flourished amid scenes of natural beauty; after many miles of marches, they reached Opis (where Greeks would be found again during Alexander’s campaign) and encountered a large Persian army. Clearchus, being a formidable and cunning general, formed his men in a column only two abreast. The long, snaking line of hoplites seemed two or three times their actual number. The Persians, feeling discretion is the better part of valor, let the Greeks move on without incident. At some point, Clearchus felt confident that the Persians really wanted to help them reach home (as was probably in their best interest) and wanted to squash the beef; he called for a council of the army telling them that he would approach Tissafernes and re-new the truce to improve their relationship; ironically, a young hoplite (a nobody) voiced his concern and distrust of the Persians, with most of the army agreeing. The thick-headed Spartan did not listen and arranged for a dinner with the Persian satrap in their camp; he took with him the army’s most prominent captains: Proxenus, Menon the Thessalian, Agias the Arcadian, and Socrates the Achaean. They were welcomed by the satrap, offered wine and enjoyed the feast until they didn’t; the “Rains of Castamere” music would be a fitting ambient here. The treacherous satrap rounded them up and executed them, hoping that this would break the Greek army and cause their immediate surrender; the army got the news by a soldier, who holding his intestines in his hands after being slashed during the massacre, run the distance from one camp to the other to alert them.. gruesome sight. That evening the Greeks shivered in their cloaks, so depressed that few kindled campfires and fewer still bothered to eat; our boys were left stranded for a second time without a leader and things were looking extremely bad.

Xenophon: a reluctant Hero

Seeing the army in such a bad state and realizing they would be soon overrun by the Persians, our young captain, Xenophon, called for an army council. He gave a greatly inspiring speech, dismissing promptly some minor sissy-talk about surrender; instead of a quick surrender, the Greeks elected new leaders, including Xenophon along with Cheirisophus, the old Spartan. It was Xenophon, who proposed to the war council to drop all their loot, leave anything but the weapons behind and immediately set off northwards, towards the Black Sea in search of friendly territories. Xenophon’s fiery speech bolstered the army’s morale and its determination to embark on the perilous march home. They agreed for Cheirisofus, with his elite Spartans, to lead the army from the front and for Xenophon to assume the heavy burden of leading the rear guard, where they expected the Persians to be attacking them during the march.

They agreed to march in a square formation with women, children (yes, many brought their families, lovers, hookers and slaves) and the baggage trains in the middle, protected. Soon the Persians came and started harassing the army, shooting arrows while riding their horses, killing and mutilating anyone who they managed to isolate; it was an extremely perilous situation as the heavy hoplites could not chase on foot the Persian cavalry. After many skirmishes and seeing the futility of their efforts, Xenophon came up with a plan: they needed missile infantry and more mobility. He quickly formed a corps of bowmen (Cretans were extremely good with the bow) and slingers (Rhodians were excellent slingers – “peltastes”, among others) which proved to be life-saving as they could now counter the barbarians; they also rounded all their horses and mules and formed up a 50-men strong cavalry detachment so they could actually chase away the enemy.

The Persian forces got cocky and over the next days they gave battle; they attacked with 5000 men and this gave the opportunity to the Hellenes to give them a surprise they would not forget; first, they unleashed the archers and superior slingers and then the horsemen rode down the startled enemy before they even knew what hit them. Many Persians died and a few were captured; the Greeks could now avenge their fallen brothers. The forced march continued and soon the countryside began to change, and at times the road led them through narrow ridges and rolling hills causing the “phalanx square” to lose cohesion and sometimes they paid for it, as Persians kept pursuing and killing stragglers. Our boys finally reached the headwaters of the Tigris River, but found to their dismay the strong current and bone-chilling waters were too deep to cross. Greek ingenuity was employed and it was suggested to cross the river with a line of inflated animal skin floats fastened together like buoys, a tactic that Alexander would also use much later; but Persian cavalry was waiting on the other side so the plan was rejected; their only way was through the mountains of Kurdistan; and the unruly Kurds (Carduchians) even though they hated the Persians, would not welcome the Greeks either. The Persians knew it and abandoned chase, for now.

The Hellenes soon started reaching the first Kurdish villages finding them abandoned; they were careful not to pillage (as they wanted to ally with these people) but they soon realized this was not going to happen; the Kurds fell on the rear guard and caused losses that same evening. Xenophon’s rear seemed to get the worst of it, and he got so heavily engaged that he sent messages to Cheirisophus, in the front, asking him to halt and wait for the rear to catch up. The Spartan old general (who usually complied) ignored the plea and started running with his elite soldiers forward. A large gap now separated the van and the rear guard, and there was a distinct possibility that Xenophon would be cut off and annihilated.

Xenophon’s men conducted a fighting retreat and managed to link up with the vanguard, where the young Athenian reproached the old Spartan (also keep in mind the dynamics, like the fact that back home their cities almost annihilated each other, and Sparta won); “take a look at the mountains,” said the old Spartan, “and observe how impassable all of them are. The only road is the one there now you can see them blocking it with a great force”; the Spartan continued, “That’s the reason why I did not wait for you, for I hoped to reach the pass and occupy it before they did.” But they lost that race and now they seemed trapped between mountains; they brought up a couple of local prisoners and one revealed another passage. They fought their way through it with bitter cold and losses wearing them down day and night. They eventually managed to go through the mountains and started descending on another valley where their route was blocked by eastern Tigris; on the opposite shore, they saw Persians and mercenaries waiting to kill them, while huge masses of Carduchians were consolidating on the mountains they just came down from. No way forward, no way back.

Our boys despaired once again, including Xenophon; that night he saw a dream about breaking chains and this was interpreted as a good omen. Soon, some scouts came back with news that they found a passage in the river so they could cross it. They did cross it and managed to find an abandoned villa/palace where they encamped; it was now November and heavy snow started engulfing them. A bitter north wind blew directly into their faces, chilling the Greeks as they plodded through the snow-drifts. Snowdrifts reached heights of six feet, and men and animals began to perish from exposure (keep in mind that this kind of conditions killed Napoleon’s and Hitler’s modern armies). The Greeks are not accustomed to heavy cold and were unprepared for cold weather. Much of the campaign had been on the sunbaked valleys of Mesopotamia, and the Greeks had dressed accordingly. Flimsy wool tunics were inadequate, and even heavy military cloaks did little to keep out the freezing cold. They struggled on, breath misting in great clouds of smokey vapor as they trudged through the snowdrifts. Sandals and boots left feet exposed to the elements, and many lost toes to frostbite. Hunger started gnawing on them, many drifting behind and just freezing to death during the constant marches. Most men had lost all hope at some point; even the instinct for self-preservation was gone. Some begged Xenophon to kill them; even death was preferable to the abject misery of the march. He refused, and many times he started beating them to go on, sending able-bodied men back to retrieve them. They kept going through the mountains of Armenia, many succumbing on the way, week after week; their misery and problems were endless with the march through the mountains proving deadly.

They kept going through the mountains until a moment that Xenophon, from the rear, started hearing yelling and clashes of shields while seeing disorder on the front; he thought the vanguard was battling with someone and rushed to see what was going on the top of the summit. He reached the top and saw a spectacle he never thought he could see again: the Sea. The men were yelling “Thalatta! Thalatta!” (the Sea, the Sea) and hugging each other like madmen; they had made it to their beloved sea… this phrase still gives me the chills.

Seeing the army in such a bad state and realizing they would be soon overrun by the Persians, our young captain, Xenophon, called for an army council. He gave a greatly inspiring speech, dismissing promptly some minor sissy-talk about surrender; instead of a quick surrender, the Greeks elected new leaders, including Xenophon along with Cheirisophus, the old Spartan. It was Xenophon, who proposed to the war council to drop all their loot, leave anything but the weapons behind and immediately set off northwards, towards the Black Sea in search of friendly territories. Xenophon’s fiery speech bolstered the army’s morale and its determination to embark on the perilous march home. They agreed for Cheirisofus, with his elite Spartans, to lead the army from the front and for Xenophon to assume the heavy burden of leading the rear guard, where they expected the Persians to be attacking them during the march.

They agreed to march in a square formation with women, children (yes, many brought their families, lovers, hookers and slaves) and the baggage trains in the middle, protected. Soon the Persians came and started harassing the army, shooting arrows while riding their horses, killing and mutilating anyone who they managed to isolate; it was an extremely perilous situation as the heavy hoplites could not chase on foot the Persian cavalry. After many skirmishes and seeing the futility of their efforts, Xenophon came up with a plan: they needed missile infantry and more mobility. He quickly formed a corps of bowmen (Cretans were extremely good with the bow) and slingers (Rhodians were excellent slingers – “peltastes”, among others) which proved to be life-saving as they could now counter the barbarians; they also rounded all their horses and mules and formed up a 50-men strong cavalry detachment so they could actually chase away the enemy.

The Persian forces got cocky and over the next days they gave battle; they attacked with 5000 men and this gave the opportunity to the Hellenes to give them a surprise they would not forget; first, they unleashed the archers and superior slingers and then the horsemen rode down the startled enemy before they even knew what hit them. Many Persians died and a few were captured; the Greeks could now avenge their fallen brothers. The forced march continued and soon the countryside began to change, and at times the road led them through narrow ridges and rolling hills causing the “phalanx square” to lose cohesion and sometimes they paid for it, as Persians kept pursuing and killing stragglers. Our boys finally reached the headwaters of the Tigris River, but found to their dismay the strong current and bone-chilling waters were too deep to cross. Greek ingenuity was employed and it was suggested to cross the river with a line of inflated animal skin floats fastened together like buoys, a tactic that Alexander would also use much later; but Persian cavalry was waiting on the other side so the plan was rejected; their only way was through the mountains of Kurdistan; and the unruly Kurds (Carduchians) even though they hated the Persians, would not welcome the Greeks either. The Persians knew it and abandoned chase, for now.

The Hellenes soon started reaching the first Kurdish villages finding them abandoned; they were careful not to pillage (as they wanted to ally with these people) but they soon realized this was not going to happen; the Kurds fell on the rear guard and caused losses that same evening. Xenophon’s rear seemed to get the worst of it, and he got so heavily engaged that he sent messages to Cheirisophus, in the front, asking him to halt and wait for the rear to catch up. The Spartan old general (who usually complied) ignored the plea and started running with his elite soldiers forward. A large gap now separated the van and the rear guard, and there was a distinct possibility that Xenophon would be cut off and annihilated.

Xenophon’s men conducted a fighting retreat and managed to link up with the vanguard, where the young Athenian reproached the old Spartan (also keep in mind the dynamics, like the fact that back home their cities almost annihilated each other, and Sparta won); “take a look at the mountains,” said the old Spartan, “and observe how impassable all of them are. The only road is the one there now you can see them blocking it with a great force”; the Spartan continued, “That’s the reason why I did not wait for you, for I hoped to reach the pass and occupy it before they did.” But they lost that race and now they seemed trapped between mountains; they brought up a couple of local prisoners and one revealed another passage. They fought their way through it with bitter cold and losses wearing them down day and night. They eventually managed to go through the mountains and started descending on another valley where their route was blocked by eastern Tigris; on the opposite shore, they saw Persians and mercenaries waiting to kill them, while huge masses of Carduchians were consolidating on the mountains they just came down from. No way forward, no way back.

Our boys despaired once again, including Xenophon; that night he saw a dream about breaking chains and this was interpreted as a good omen. Soon, some scouts came back with news that they found a passage in the river so they could cross it. They did cross it and managed to find an abandoned villa/palace where they encamped; it was now November and heavy snow started engulfing them. A bitter north wind blew directly into their faces, chilling the Greeks as they plodded through the snow-drifts. Snowdrifts reached heights of six feet, and men and animals began to perish from exposure (keep in mind that this kind of conditions killed Napoleon’s and Hitler’s modern armies). The Greeks are not accustomed to heavy cold and were unprepared for cold weather. Much of the campaign had been on the sunbaked valleys of Mesopotamia, and the Greeks had dressed accordingly. Flimsy wool tunics were inadequate, and even heavy military cloaks did little to keep out the freezing cold. They struggled on, breath misting in great clouds of smokey vapor as they trudged through the snowdrifts. Sandals and boots left feet exposed to the elements, and many lost toes to frostbite. Hunger started gnawing on them, many drifting behind and just freezing to death during the constant marches. Most men had lost all hope at some point; even the instinct for self-preservation was gone. Some begged Xenophon to kill them; even death was preferable to the abject misery of the march. He refused, and many times he started beating them to go on, sending able-bodied men back to retrieve them. They kept going through the mountains of Armenia, many succumbing on the way, week after week; their misery and problems were endless with the march through the mountains proving deadly.

They kept going through the mountains until a moment that Xenophon, from the rear, started hearing yelling and clashes of shields while seeing disorder on the front; he thought the vanguard was battling with someone and rushed to see what was going on the top of the summit. He reached the top and saw a spectacle he never thought he could see again: the Sea. The men were yelling “Thalatta! Thalatta!” (the Sea, the Sea) and hugging each other like madmen; they had made it to their beloved sea… this phrase still gives me the chills.

Xenophon: Catavasis – The long way back

Our boys had reached the southern shores of the Black Sea, where a multitude of Greek colonies and cities were established; the first major Greek city they encountered was Trapezus where they were welcomed by fellow Greeks. They rested and soon organized athletic games and dances to celebrate. But their struggles were far from over.

Even though battered down and tired, they still remained probably the most formidable force in the known world at that point, and they knew it; the local cities engulfed them in their regional politics to avenge their enemies or extort payments from their neighbors. Of course, our chad boys knew it and were ok with it; they even played the card of “we can be friends and destroy your enemies, or we can be enemies and destroy you”. Another major challenge was that discipline started loosening and many lesser bands started taking initiative and pillaging whatever they could lay their hands on; this of course caused casualties and complications with the locals who were not too happy to share their property with the eager chad mercs. In one of the war councils, the generals agreed that Cheirisofus should take one of the ships they were provided by the locals and travel back to a Spartan-controlled city to request help and more ships to take them all back home. After he left, Xenophon also procured more ships and sent back to Hellas, via sea, the women, children, and those men who are sick or over the age of forty.

Meanwhile, the army continued their march Westwards; they leveraged their strength and allied with cities on the way. One of those local tribes was the Mossynoecians, whose enemies the Greeks annihilated easily. Their target was to reach one of the greatest colonies nearby, Sinope, which possessed a great harbor and a naval force capable of transporting them towards the Hellespont, next to continental Hellas. Despite some initial distrust, they convinced the ambassadors of Sinope that they had friendly intentions and established good relationships; they now agreed that travelling through the sea would be the best way home but soon realized that this option had some technical challenges: they didn’t have enough ships. And even though they could “procure” some, through piracy or “leasing”, they were not enough for everyone; they knew their strength was in unity and refused to leave men behind. This is when the Greeks, being Greeks, started voicing their (too many) opinions and some started accusing Xenophon of being a tyrant; these charges were dismissed easily but dissent was making its appearance in the army.

Soon, Cheirisofus returned with bad news: he could not secure support from the Spartans and a whole fleet to take them home. He did agree with Cleandrus, a Spartan regional overlord, to try and send a fleet to go collect them soon. The army, even though they could see that only united they could make it and many started voicing their support for Xenophon to continue being the only leader, in order to manage their return, strife conquered them. Xenophon, maybe tired from the burden of leading and dealing with all their sh*t, refused to take over and supported Cheirisophus to lead; unsurprisingly, now that the worst was behind and there was no common enemy, the Greek army started fighting. The Arcadians and Achaeans (almost half the army) disagreed with having a Spartan and an Athenian as leaders and soon broke off; ironically, they disagreed because they wanted to extort those nearby Greek cities and pillage them, just because they could. Soon after, the army broke in three detachments (led by Xenophon, Cheirisofus and the Peloponnesians – Arcadians and Achaeans) and followed different routes towards mainland Greece. The Peloponnesians started attacking towns in eastern Thrace while Xenophon and Cheirisophus continued their march home; soon, the Peloponnesians got in trouble, as they got encircled and isolated on a hill surrounded by thousands of Thracians (considered barbarians by the Greeks) with no water, no food, no shelter and no hope of escape, being decimated by arrows and javelins. The news spread in the region, that a Greek army was being decimated and soon Xenophon, while leading his detachment, heard about it; he made a fiery speech and galvanized his men rushing to save the others. When the barbarians saw the chad-boys coming to save their brothers, they scattered. The Greeks hugged each other crying, realized how f**king stupid they have been and reunited, vowing death to anyone with such stupid ideas from that point on; after spending some time to bury their dead with honor, they continued their march. Meanwhile, Cheirisofus, the Spartan leader, died of sickness and old age; that old warrior did not have the glorious death a Spartan would wish for, but shall be remembered as a man of great honor nevertheless. Keep in mind that our boys were still so close and yet so far; they were still in Asia, not having crossed the Hellespont to European soil. They camped nearby, where no friendly Greek cities were, and with no provisions; therefore, having heard that they could buy stuff from nearby villages, sent out 2000 men with no arms to buy food. But the gods were not in their favor that day; soon, the local tribes ambushed and started attacking them, with the Persian cavalry who had followed them all the way from Babylonia. They knew the Greeks were exhausted and had come to finish them. Our boys could get no break; many died there and some others fortified themselves on a hill, completely surrounded and besieged. Things were looking extremely bad for the boys.

News reached the army back in camp; Xenophon mustered the troops, made sacrifices to the gods and fortified the location. They needed to go and rescue the others from the Persians; they decided to leave a detachment of men guarding the camp but could find no one willing to stay back: the boys were furious and bloodthirsty: only death would settle this score with the Persians. They sallied out to meet the Persian army and make their last stand against an empire who wanted them dead; once again, as so many times in History, a few Hellenes stood against a multitude of barbarians. They realized the Persians were waiting them on a hilly, wooded area. Xenophon having the army lined up for battle in Phalanx formation walked back and forth shouting: “You men have stood against those Persians so many times and beaten them; remember your victories, remember who WE ARE, REMEMBER WE ARE AT THE GATES OF GREECE, REMEMBER OUR ANCESTORS, REMEMBER HERCULES! REMEMBER YOUR NAMES! A sound started coming from the army.. a deep murmur that became a battle cry was being chanted in total sync from thousands of men.. you know very GODDAMNED WELL what’s coming next. After a short engagement between the ranged detachments, the phalanx started rushing the hill upwards singing their war chants. They massacred the Persians who scattered and regrouped with the local tribes on a nearby hill; our boys rushed them again and annihilated them, while the Persian army remnants scattered in the woods. The day was theirs!

After that point, things got better; much better. Since our boys had proven again who’s the top dog in the region, friendly cities started supplying them and hostile ones started sending envoys to ask what they had to do to become friends of the Greeks. There were also rumors that they would probably establish a new city there and dominate the region. Meanwhile, a Spartan embassy from Byzantium arrived, led by Cleandrus; keep in mind that the Greek world was now dominated by Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian war, so they were the ones to manage all Greek matters, on paper, including the one of the return of 10.000 men from deep Persia. After some initial misunderstandings, and with Xenophon’s shrewd diplomacy, an agreement was reached between the Spartans and our boys, that they would be welcomed back in Europe, in Byzantium. It is mentioned though that even Cleandrus, a spartan general renowned in the Greek world, was impressed by the martial prowess and organization of the Greek mercenary army and even volunteered to lead them back home himself. The Persian local satrap, whose army was beaten decisively in the previous battle, was terribly afraid of them and sent envoys to the Spartan commanders to hurry the crossing of the army to Europe; ironically, the Spartans were in great terms with the Persians (at that point), since the latter had financed them during the Peloponnesian war (Greeks being Greeks…). Salaries were promised to our boys, to sweeten the deal (also necessary for them, so they could procure food from markets), and they crossed with the ships of the Spartan admiral Anaxibius; they reached Byzantium where the Spartans treated them badly despite the deals; he did not allow them to enter but told them to keep marching to the next city, where they would get their salaries; our boys were beaten, hungry and double-crossed. One word brought another, since the Spartans were not known generally for their kind attitude, and chaos erupted; the boys stormed the city and took it, ready to pillage and destroy it. The citizens run to their houses, the spartan guard fortified itself in the acropolis and their captains run away; they didn’t look so tough now. Xenophon, always the cool headed, jumped in front of the boys, to save them from doing something stupid against fellow-Greeks; they complied and the situation calmed down. A lot of miscommunications and miscoordination ensued, together with the coming of new Spartan commanders – to replace the old ones in the region, and soon, the Spartans started arresting whoever they would find foraging away from the army; it is said that they arrested and sold them as slaves, more than 400 of our dudes.

Their misfortunes were endless; they were now in Europe and their fellow Greeks were not just refusing to help them but attacked them. An opportunity came soon through an invitation of a local Thracian warlord who wanted to hire them to reclaim his crown; he promised them refuge, land and money; they had no alternative. After two months and minor battles in the midst of winter against barbarians, the warlord had not paid their salaries in full, asking them to wait some more; mutiny was now a real possibility and just when they were ready to fight against their allies, Spartan envoys came and announced that now Sparta had declared war to the Persians and their services were needed. They ferried them (again) back in Asia and reunited them with the rest of the Greek regulars; they marched together united under Hellenic Spartan banners and this is when another bad hombre and one of the greatest warrior kings Greece has produced, Agesilaus, comes into the story (check my other piece on him in my highlights). The Greeks, united now, campaigned together and devastated the Persians before coming back home together; our boys disbanded and continued on their own towards their home cities. Their legend would live on and their story would be told for the next thousands of years. The next time Persia would encounter a united Greek army would be under Alexander, and this was destined to be their End.

Our boys had reached the southern shores of the Black Sea, where a multitude of Greek colonies and cities were established; the first major Greek city they encountered was Trapezus where they were welcomed by fellow Greeks. They rested and soon organized athletic games and dances to celebrate. But their struggles were far from over.

Even though battered down and tired, they still remained probably the most formidable force in the known world at that point, and they knew it; the local cities engulfed them in their regional politics to avenge their enemies or extort payments from their neighbors. Of course, our chad boys knew it and were ok with it; they even played the card of “we can be friends and destroy your enemies, or we can be enemies and destroy you”. Another major challenge was that discipline started loosening and many lesser bands started taking initiative and pillaging whatever they could lay their hands on; this of course caused casualties and complications with the locals who were not too happy to share their property with the eager chad mercs. In one of the war councils, the generals agreed that Cheirisofus should take one of the ships they were provided by the locals and travel back to a Spartan-controlled city to request help and more ships to take them all back home. After he left, Xenophon also procured more ships and sent back to Hellas, via sea, the women, children, and those men who are sick or over the age of forty.

Meanwhile, the army continued their march Westwards; they leveraged their strength and allied with cities on the way. One of those local tribes was the Mossynoecians, whose enemies the Greeks annihilated easily. Their target was to reach one of the greatest colonies nearby, Sinope, which possessed a great harbor and a naval force capable of transporting them towards the Hellespont, next to continental Hellas. Despite some initial distrust, they convinced the ambassadors of Sinope that they had friendly intentions and established good relationships; they now agreed that travelling through the sea would be the best way home but soon realized that this option had some technical challenges: they didn’t have enough ships. And even though they could “procure” some, through piracy or “leasing”, they were not enough for everyone; they knew their strength was in unity and refused to leave men behind. This is when the Greeks, being Greeks, started voicing their (too many) opinions and some started accusing Xenophon of being a tyrant; these charges were dismissed easily but dissent was making its appearance in the army.

Soon, Cheirisofus returned with bad news: he could not secure support from the Spartans and a whole fleet to take them home. He did agree with Cleandrus, a Spartan regional overlord, to try and send a fleet to go collect them soon. The army, even though they could see that only united they could make it and many started voicing their support for Xenophon to continue being the only leader, in order to manage their return, strife conquered them. Xenophon, maybe tired from the burden of leading and dealing with all their sh*t, refused to take over and supported Cheirisophus to lead; unsurprisingly, now that the worst was behind and there was no common enemy, the Greek army started fighting. The Arcadians and Achaeans (almost half the army) disagreed with having a Spartan and an Athenian as leaders and soon broke off; ironically, they disagreed because they wanted to extort those nearby Greek cities and pillage them, just because they could. Soon after, the army broke in three detachments (led by Xenophon, Cheirisofus and the Peloponnesians – Arcadians and Achaeans) and followed different routes towards mainland Greece. The Peloponnesians started attacking towns in eastern Thrace while Xenophon and Cheirisophus continued their march home; soon, the Peloponnesians got in trouble, as they got encircled and isolated on a hill surrounded by thousands of Thracians (considered barbarians by the Greeks) with no water, no food, no shelter and no hope of escape, being decimated by arrows and javelins. The news spread in the region, that a Greek army was being decimated and soon Xenophon, while leading his detachment, heard about it; he made a fiery speech and galvanized his men rushing to save the others. When the barbarians saw the chad-boys coming to save their brothers, they scattered. The Greeks hugged each other crying, realized how f**king stupid they have been and reunited, vowing death to anyone with such stupid ideas from that point on; after spending some time to bury their dead with honor, they continued their march. Meanwhile, Cheirisofus, the Spartan leader, died of sickness and old age; that old warrior did not have the glorious death a Spartan would wish for, but shall be remembered as a man of great honor nevertheless. Keep in mind that our boys were still so close and yet so far; they were still in Asia, not having crossed the Hellespont to European soil. They camped nearby, where no friendly Greek cities were, and with no provisions; therefore, having heard that they could buy stuff from nearby villages, sent out 2000 men with no arms to buy food. But the gods were not in their favor that day; soon, the local tribes ambushed and started attacking them, with the Persian cavalry who had followed them all the way from Babylonia. They knew the Greeks were exhausted and had come to finish them. Our boys could get no break; many died there and some others fortified themselves on a hill, completely surrounded and besieged. Things were looking extremely bad for the boys.

News reached the army back in camp; Xenophon mustered the troops, made sacrifices to the gods and fortified the location. They needed to go and rescue the others from the Persians; they decided to leave a detachment of men guarding the camp but could find no one willing to stay back: the boys were furious and bloodthirsty: only death would settle this score with the Persians. They sallied out to meet the Persian army and make their last stand against an empire who wanted them dead; once again, as so many times in History, a few Hellenes stood against a multitude of barbarians. They realized the Persians were waiting them on a hilly, wooded area. Xenophon having the army lined up for battle in Phalanx formation walked back and forth shouting: “You men have stood against those Persians so many times and beaten them; remember your victories, remember who WE ARE, REMEMBER WE ARE AT THE GATES OF GREECE, REMEMBER OUR ANCESTORS, REMEMBER HERCULES! REMEMBER YOUR NAMES! A sound started coming from the army.. a deep murmur that became a battle cry was being chanted in total sync from thousands of men.. you know very GODDAMNED WELL what’s coming next. After a short engagement between the ranged detachments, the phalanx started rushing the hill upwards singing their war chants. They massacred the Persians who scattered and regrouped with the local tribes on a nearby hill; our boys rushed them again and annihilated them, while the Persian army remnants scattered in the woods. The day was theirs!

After that point, things got better; much better. Since our boys had proven again who’s the top dog in the region, friendly cities started supplying them and hostile ones started sending envoys to ask what they had to do to become friends of the Greeks. There were also rumors that they would probably establish a new city there and dominate the region. Meanwhile, a Spartan embassy from Byzantium arrived, led by Cleandrus; keep in mind that the Greek world was now dominated by Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian war, so they were the ones to manage all Greek matters, on paper, including the one of the return of 10.000 men from deep Persia. After some initial misunderstandings, and with Xenophon’s shrewd diplomacy, an agreement was reached between the Spartans and our boys, that they would be welcomed back in Europe, in Byzantium. It is mentioned though that even Cleandrus, a spartan general renowned in the Greek world, was impressed by the martial prowess and organization of the Greek mercenary army and even volunteered to lead them back home himself. The Persian local satrap, whose army was beaten decisively in the previous battle, was terribly afraid of them and sent envoys to the Spartan commanders to hurry the crossing of the army to Europe; ironically, the Spartans were in great terms with the Persians (at that point), since the latter had financed them during the Peloponnesian war (Greeks being Greeks…). Salaries were promised to our boys, to sweeten the deal (also necessary for them, so they could procure food from markets), and they crossed with the ships of the Spartan admiral Anaxibius; they reached Byzantium where the Spartans treated them badly despite the deals; he did not allow them to enter but told them to keep marching to the next city, where they would get their salaries; our boys were beaten, hungry and double-crossed. One word brought another, since the Spartans were not known generally for their kind attitude, and chaos erupted; the boys stormed the city and took it, ready to pillage and destroy it. The citizens run to their houses, the spartan guard fortified itself in the acropolis and their captains run away; they didn’t look so tough now. Xenophon, always the cool headed, jumped in front of the boys, to save them from doing something stupid against fellow-Greeks; they complied and the situation calmed down. A lot of miscommunications and miscoordination ensued, together with the coming of new Spartan commanders – to replace the old ones in the region, and soon, the Spartans started arresting whoever they would find foraging away from the army; it is said that they arrested and sold them as slaves, more than 400 of our dudes.

Their misfortunes were endless; they were now in Europe and their fellow Greeks were not just refusing to help them but attacked them. An opportunity came soon through an invitation of a local Thracian warlord who wanted to hire them to reclaim his crown; he promised them refuge, land and money; they had no alternative. After two months and minor battles in the midst of winter against barbarians, the warlord had not paid their salaries in full, asking them to wait some more; mutiny was now a real possibility and just when they were ready to fight against their allies, Spartan envoys came and announced that now Sparta had declared war to the Persians and their services were needed. They ferried them (again) back in Asia and reunited them with the rest of the Greek regulars; they marched together united under Hellenic Spartan banners and this is when another bad hombre and one of the greatest warrior kings Greece has produced, Agesilaus, comes into the story (check my other piece on him in my highlights). The Greeks, united now, campaigned together and devastated the Persians before coming back home together; our boys disbanded and continued on their own towards their home cities. Their legend would live on and their story would be told for the next thousands of years. The next time Persia would encounter a united Greek army would be under Alexander, and this was destined to be their End.

Aftermath and Thoughts:

I guess this is the part of the movie that informs you what happened to the main characters after the end; well, Xenophon survived and became a true friend to Agesilaus and Cleandrus; he admired Spartan discipline and their laconic philosophy, to the point that he joined them in a battle against his own city, Athens. He was exiled by the Athenians but the Spartans gave him some good land in the Peloponnese, close to Olympia; he erected temples to Artemis and lived there for many good years with his wife and sons. He wrote there his numerous historic works and memoirs.

This is how an Epic Saga looks like ladies and gentlemen; a legendary band of brothers, a truly dysfunctional large family of adventurers that went asking and found out that when you live by the sword, it is most probable that you will die by it. They spent 15 whole months, marched more than 5000 miles, lost thousands of their comrades, fought against countless enemies and tribes didn’t know existed and grinded through valleys and mountains, deserts and forests, snow and heat, pain and glory. They saw their brothers die, lost limbs, hopes and dreams but they gained eternal glory, as their journey has been immortalized and shall be remembered throughout eternity; this is the story of the 10.000.

I guess this is the part of the movie that informs you what happened to the main characters after the end; well, Xenophon survived and became a true friend to Agesilaus and Cleandrus; he admired Spartan discipline and their laconic philosophy, to the point that he joined them in a battle against his own city, Athens. He was exiled by the Athenians but the Spartans gave him some good land in the Peloponnese, close to Olympia; he erected temples to Artemis and lived there for many good years with his wife and sons. He wrote there his numerous historic works and memoirs.

This is how an Epic Saga looks like ladies and gentlemen; a legendary band of brothers, a truly dysfunctional large family of adventurers that went asking and found out that when you live by the sword, it is most probable that you will die by it. They spent 15 whole months, marched more than 5000 miles, lost thousands of their comrades, fought against countless enemies and tribes didn’t know existed and grinded through valleys and mountains, deserts and forests, snow and heat, pain and glory. They saw their brothers die, lost limbs, hopes and dreams but they gained eternal glory, as their journey has been immortalized and shall be remembered throughout eternity; this is the story of the 10.000.

Loading suggestions...