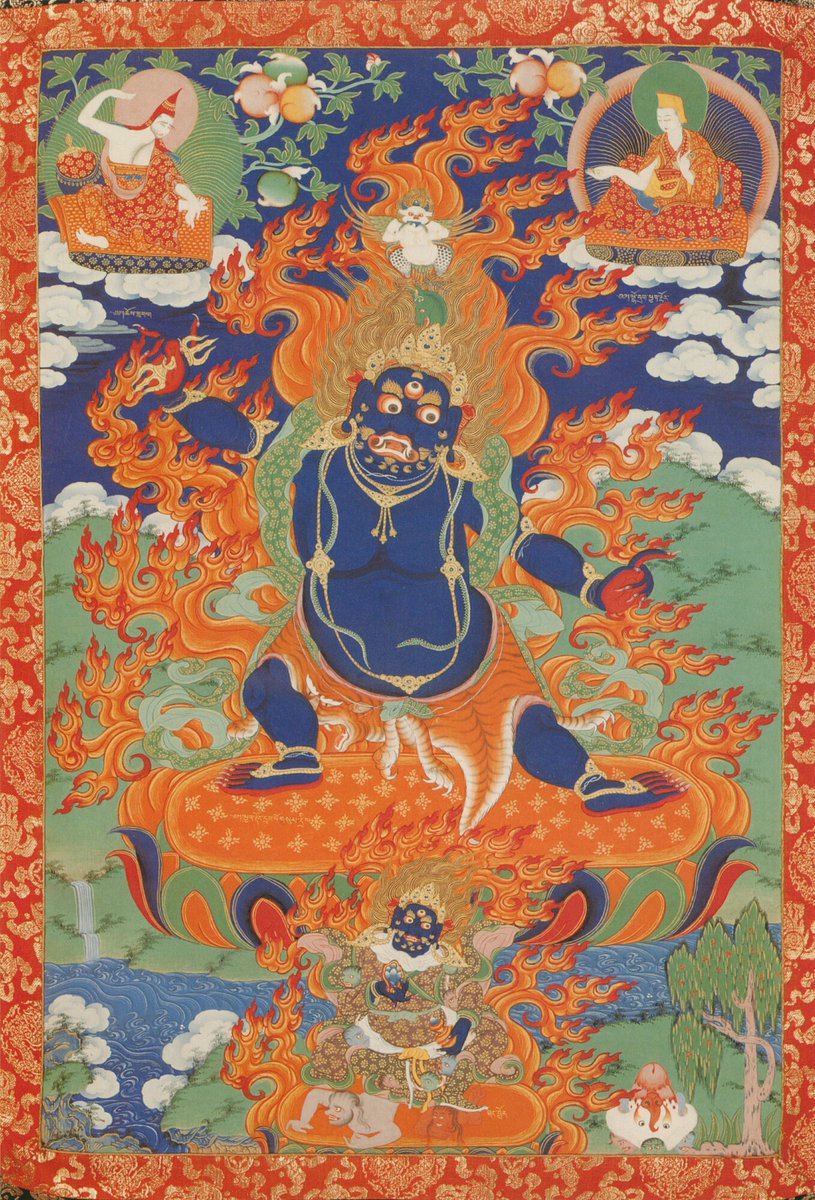

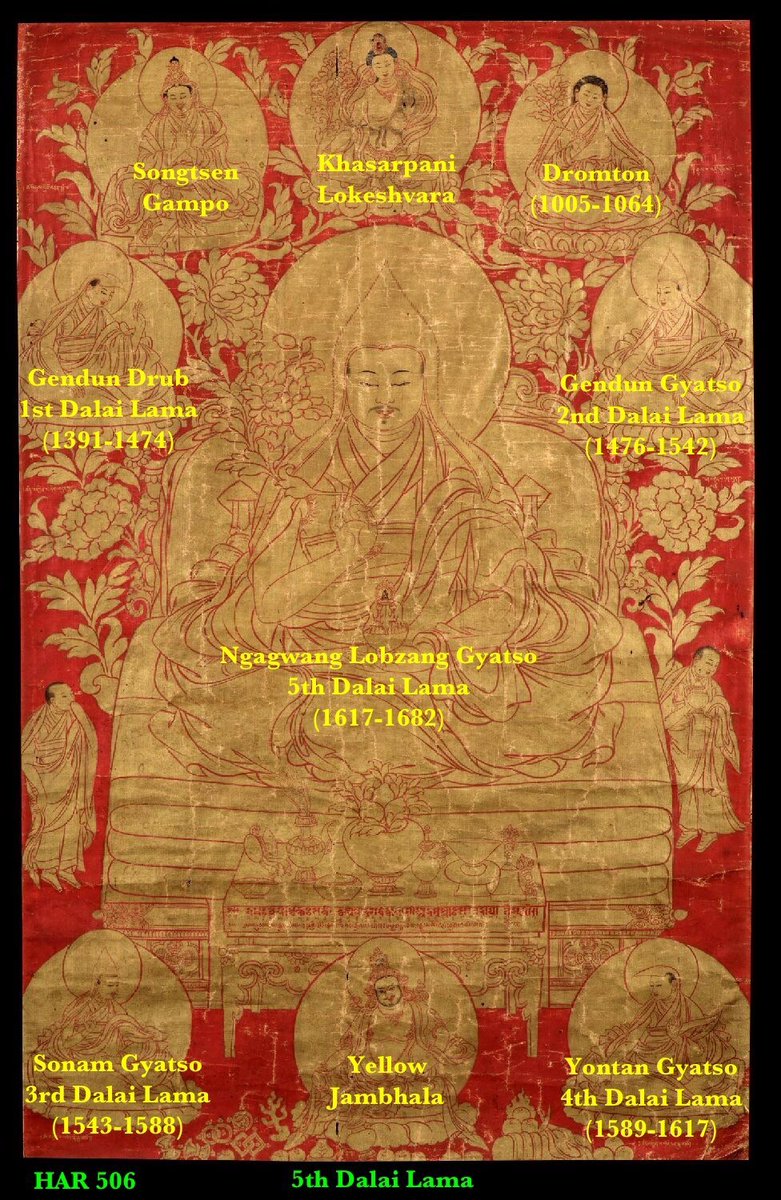

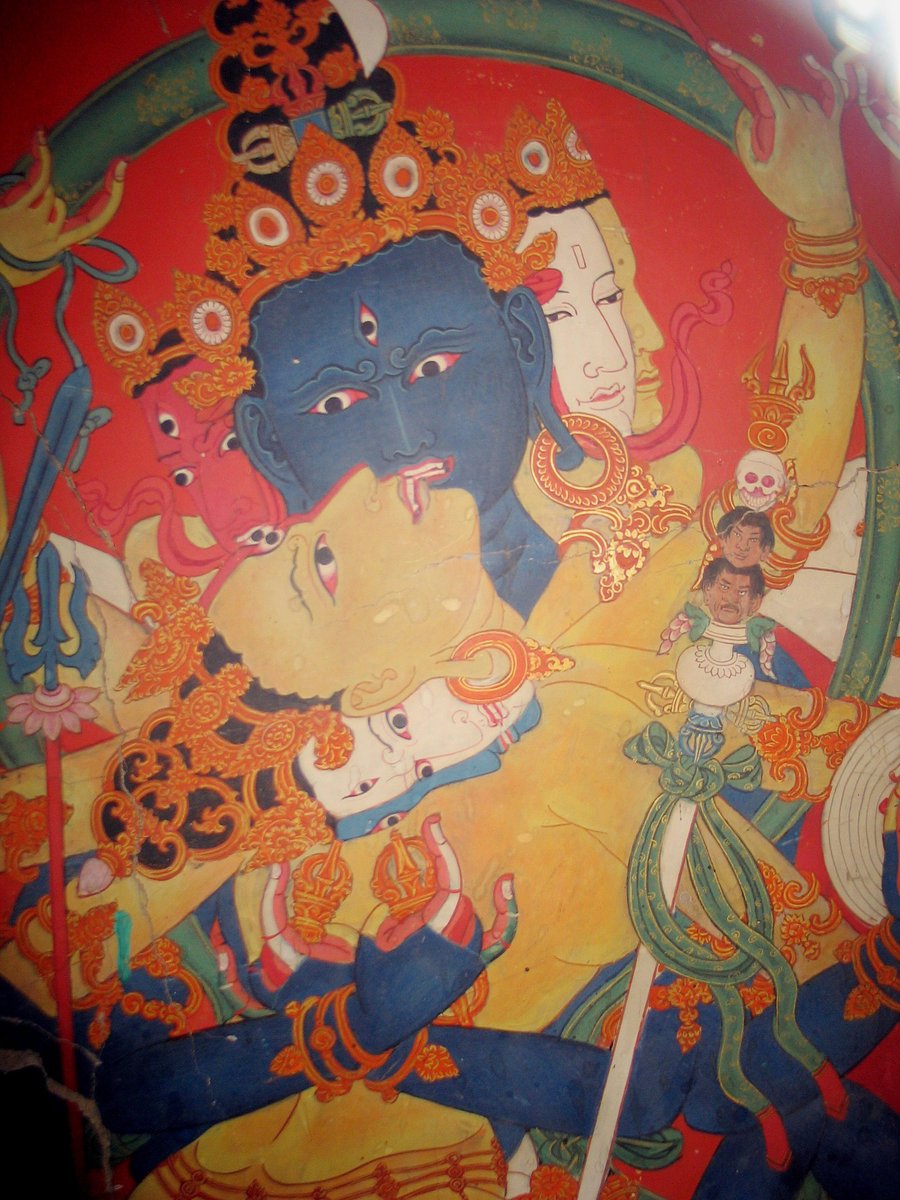

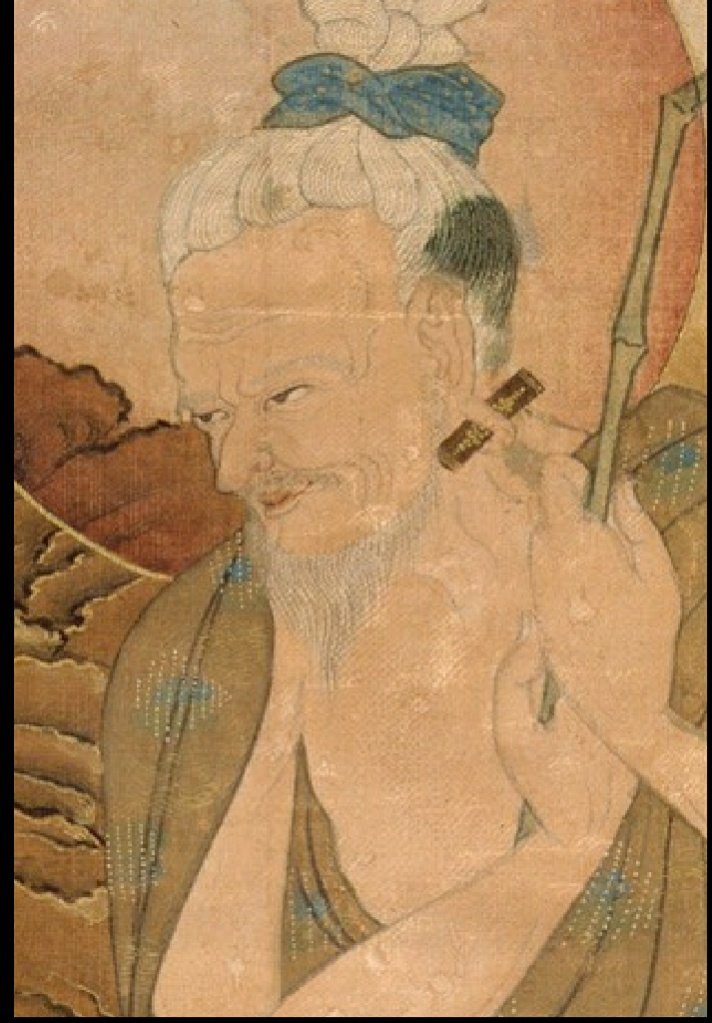

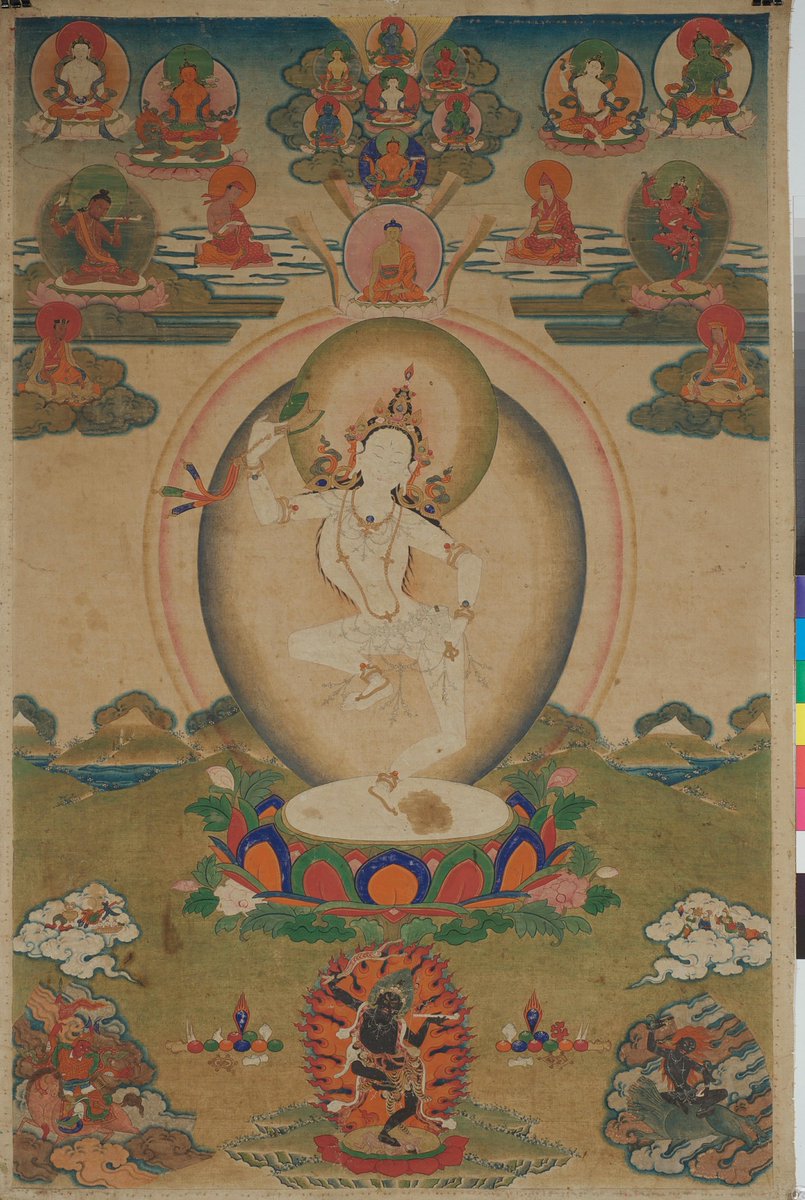

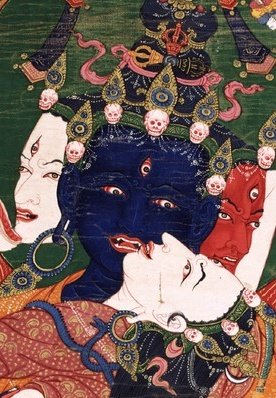

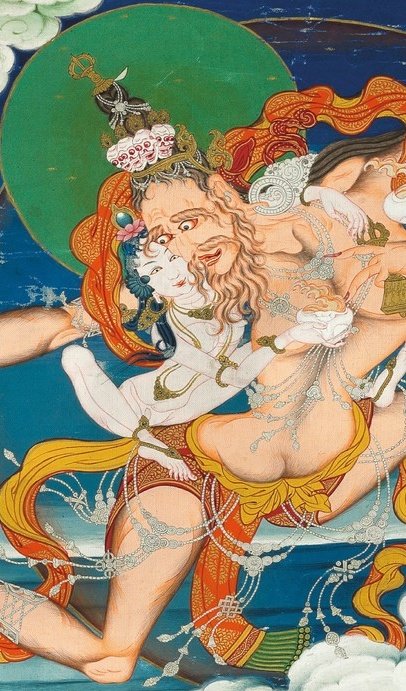

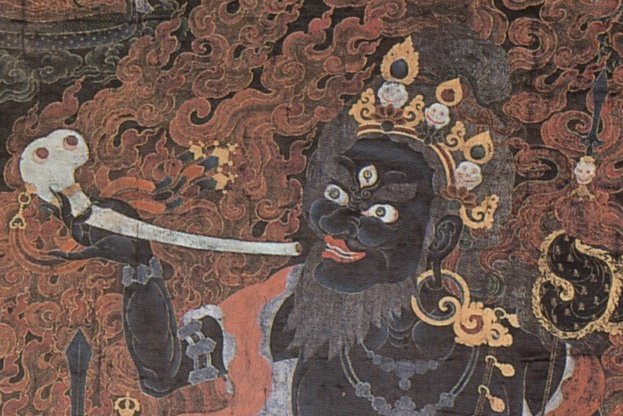

As monasteries developed in Tibet, regional styles evolved to cater to the tastes of the local monastery. While Western Tibet was influenced earlier on by Indian and Nepali art, Eastern and later Tibetan art was influenced by the Chinese.

Loading suggestions...