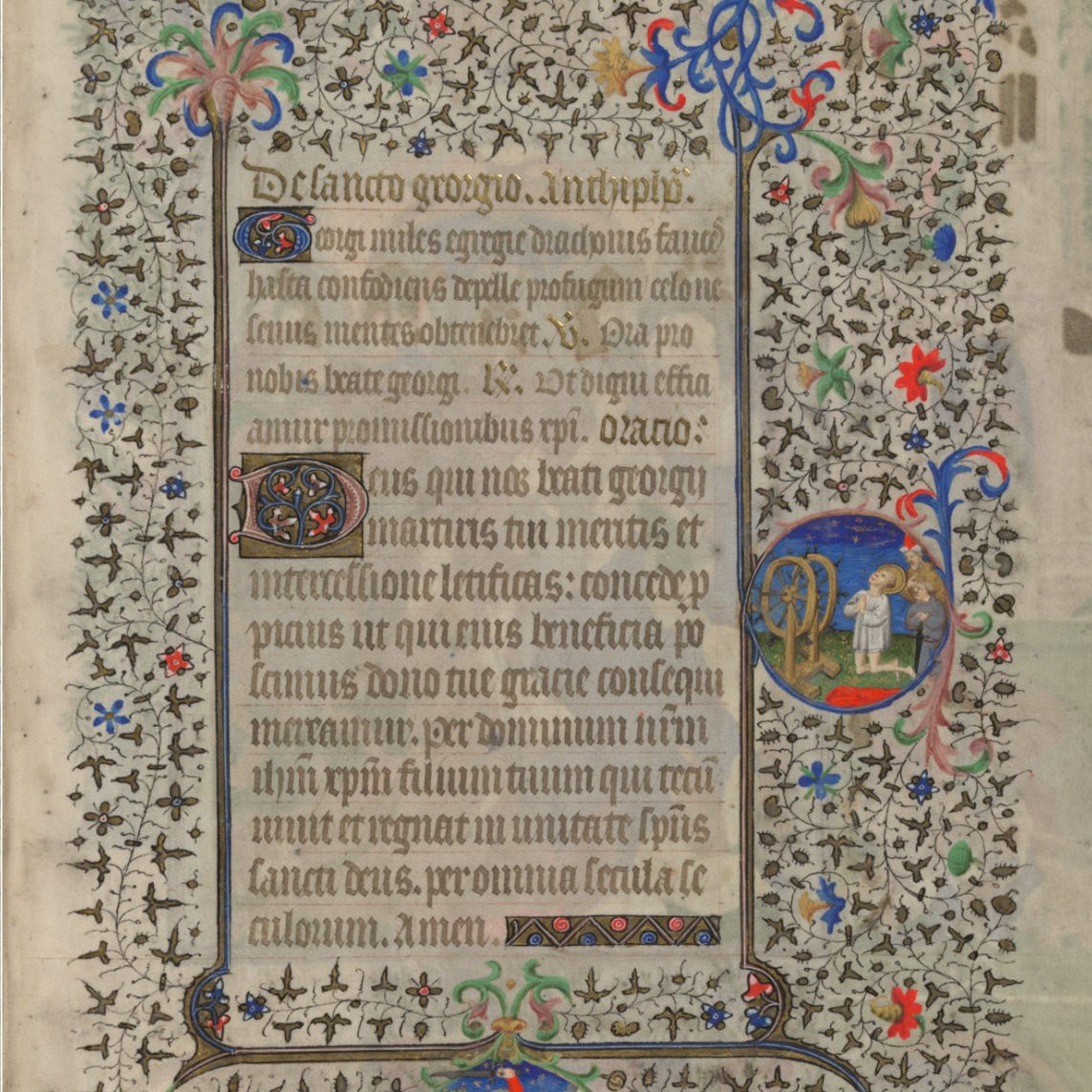

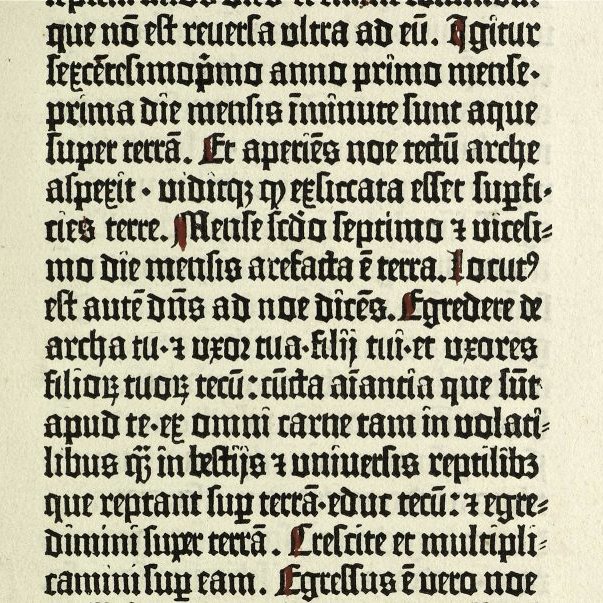

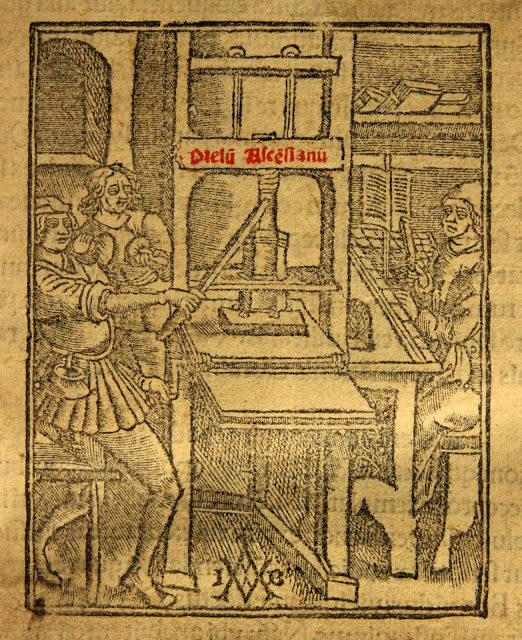

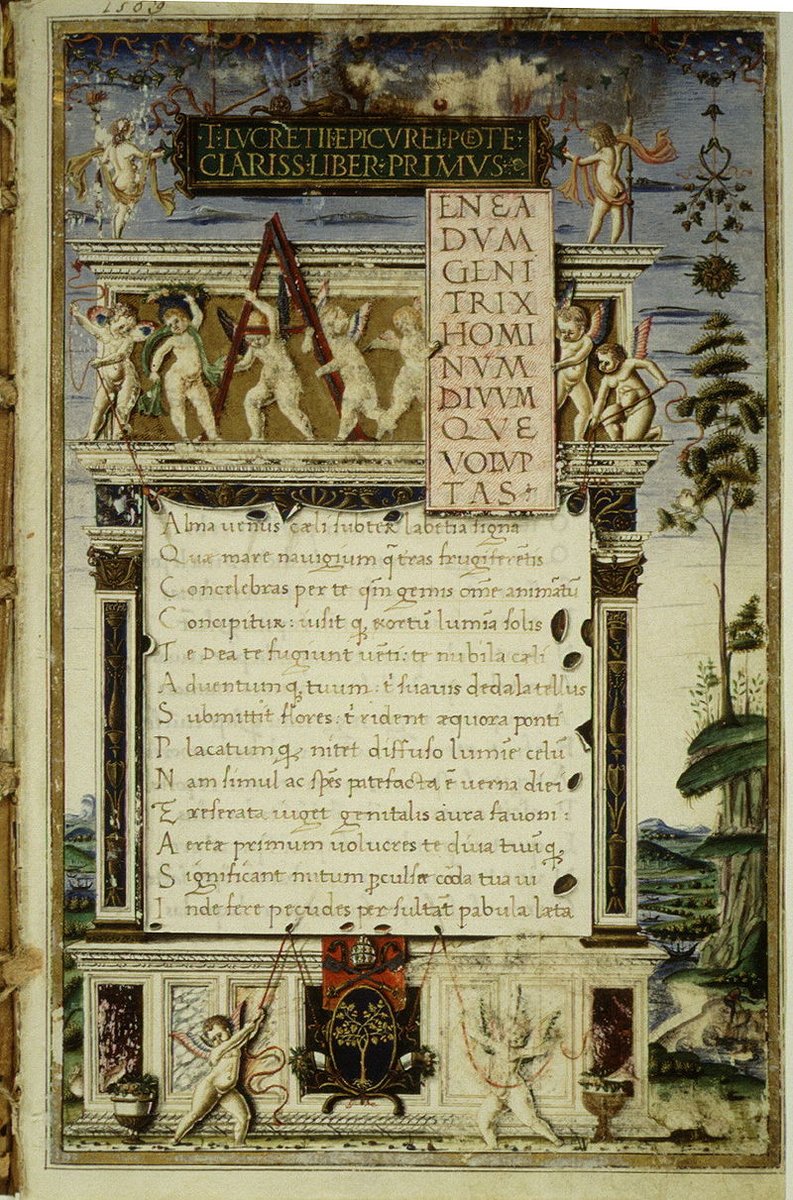

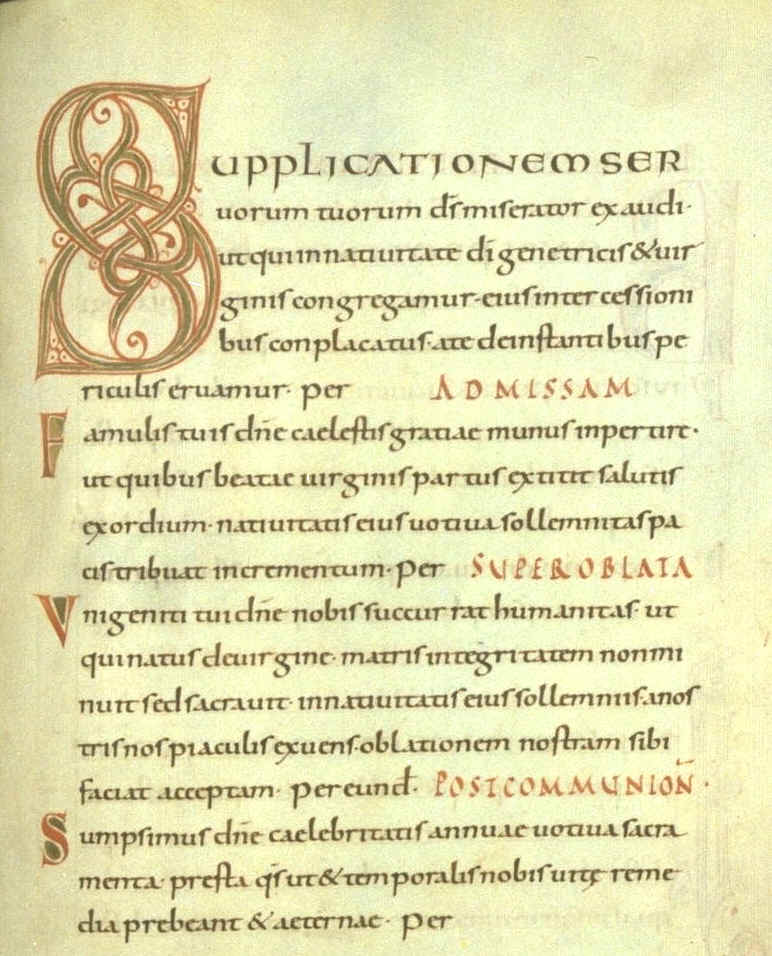

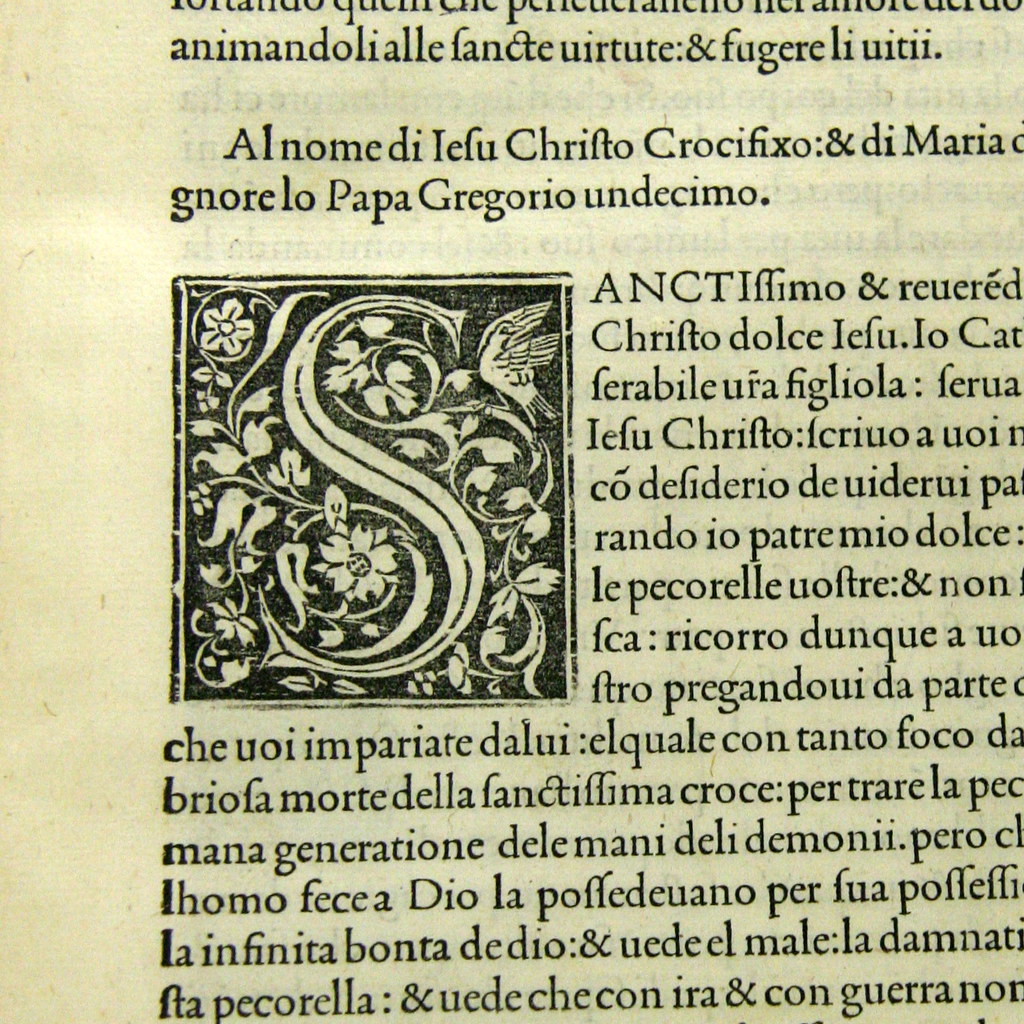

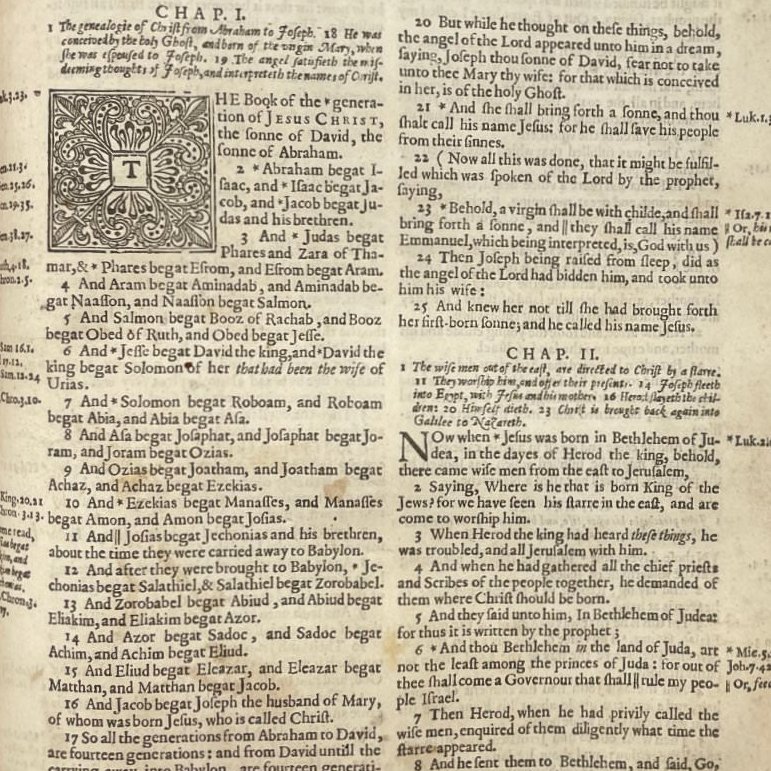

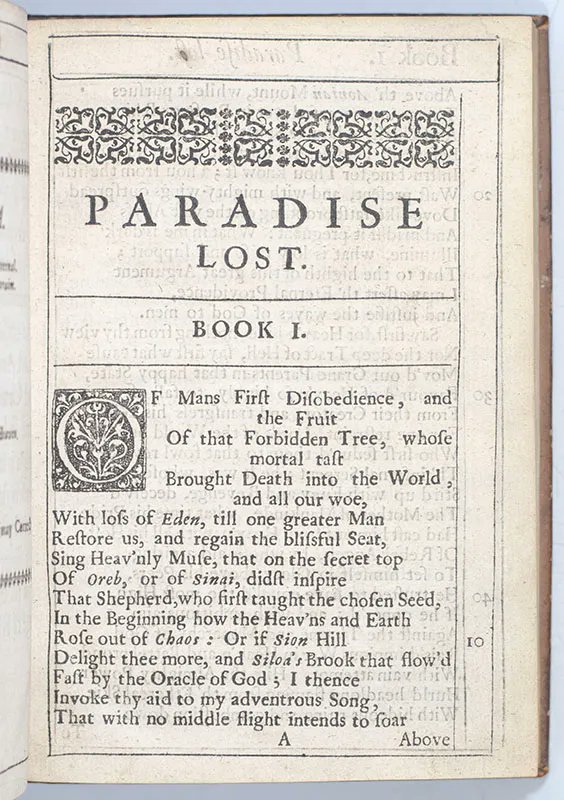

But... it wasn't obvious what font or typeface these new books should be printed in.

A helpsome clarification: "typeface" refers to an overall style of letter design, whereas "font" refers to specific varations on that style.

Roman is a typeface; Times New Roman is a font.

A helpsome clarification: "typeface" refers to an overall style of letter design, whereas "font" refers to specific varations on that style.

Roman is a typeface; Times New Roman is a font.

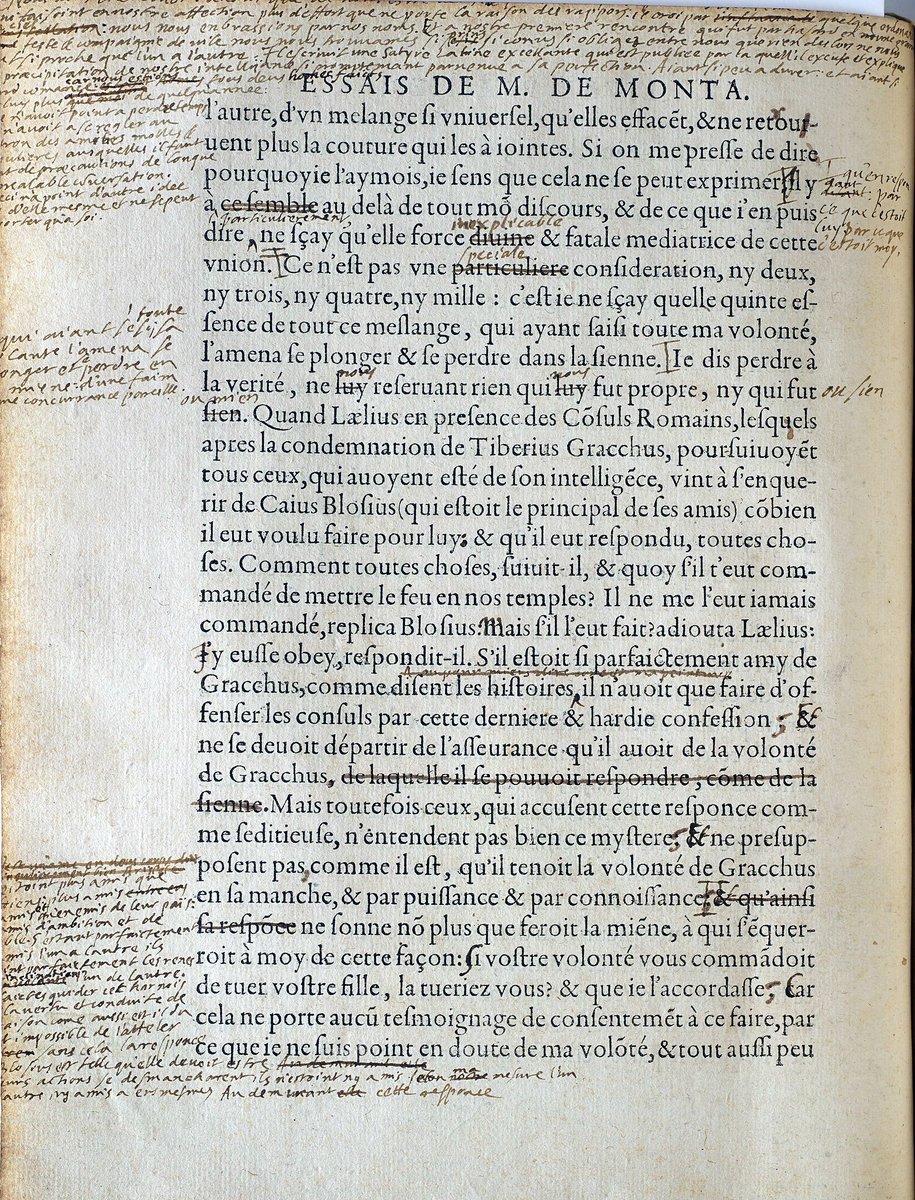

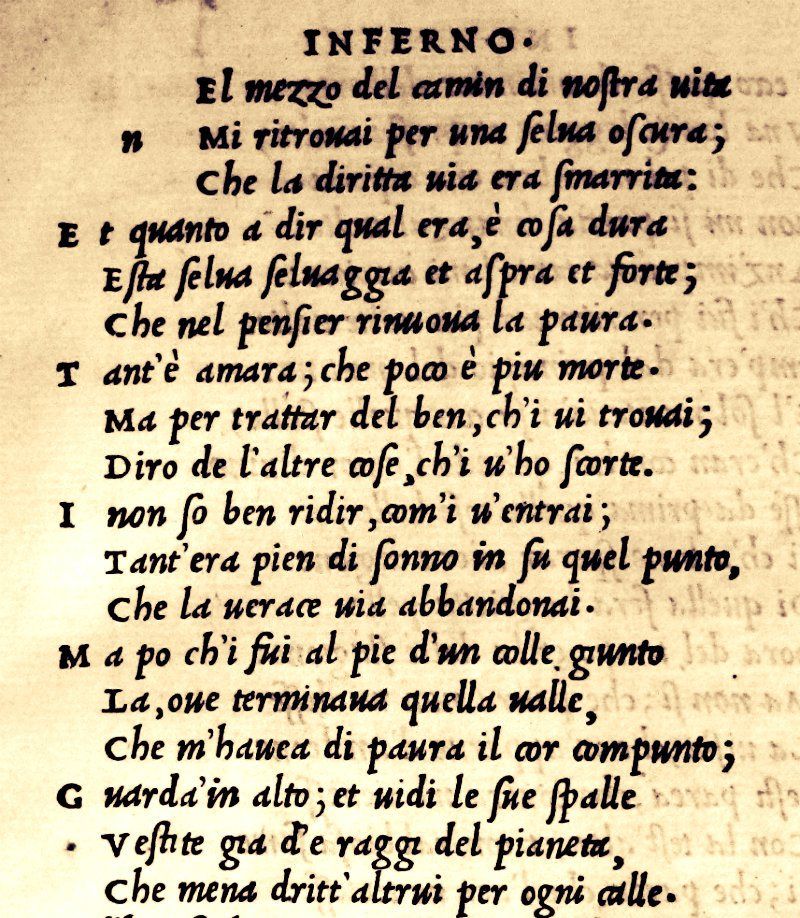

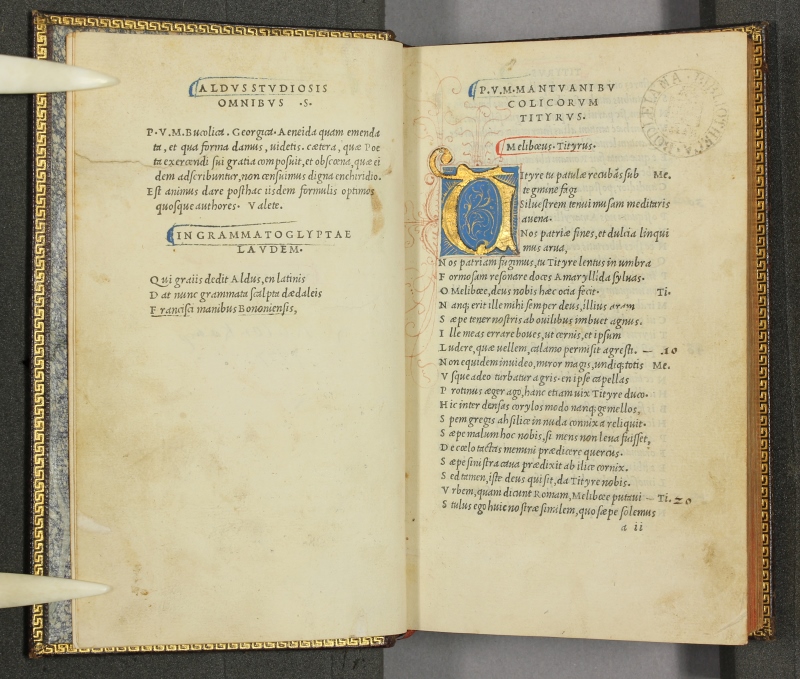

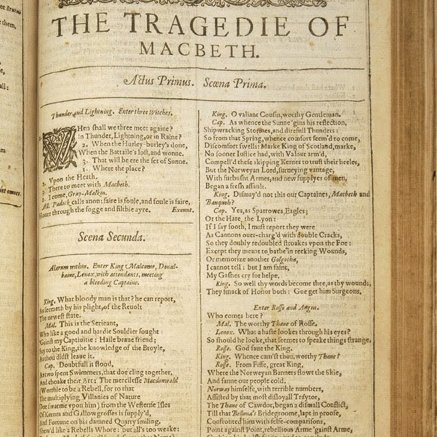

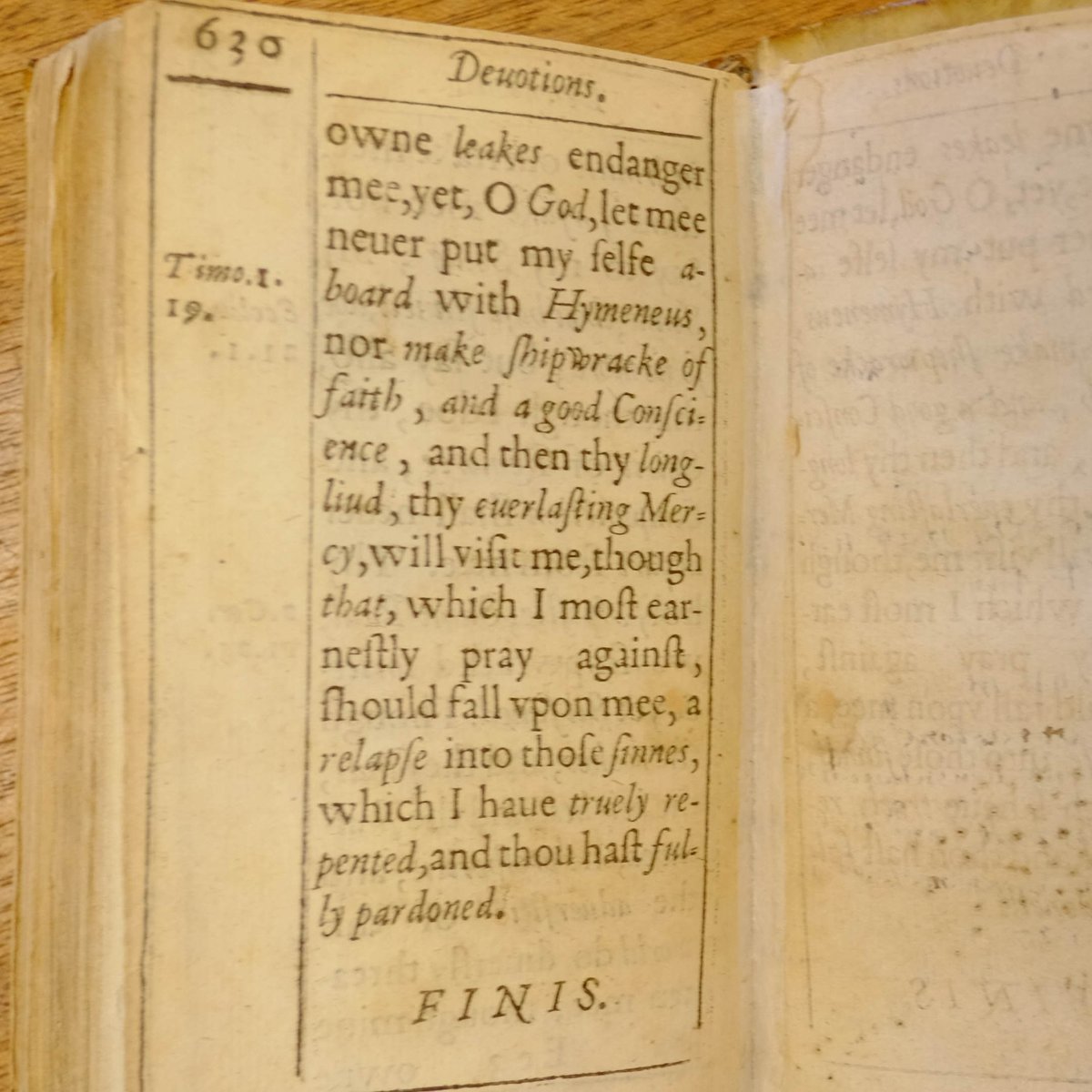

And thus, slowly but surely, our modern usage of italics was formed: to emphasise a word, to indicate names (e.g. of a film), to indicate a different purpose (e.g. stage directions), or to indicate a different voice, such as internal monologue or flashback, in novels.

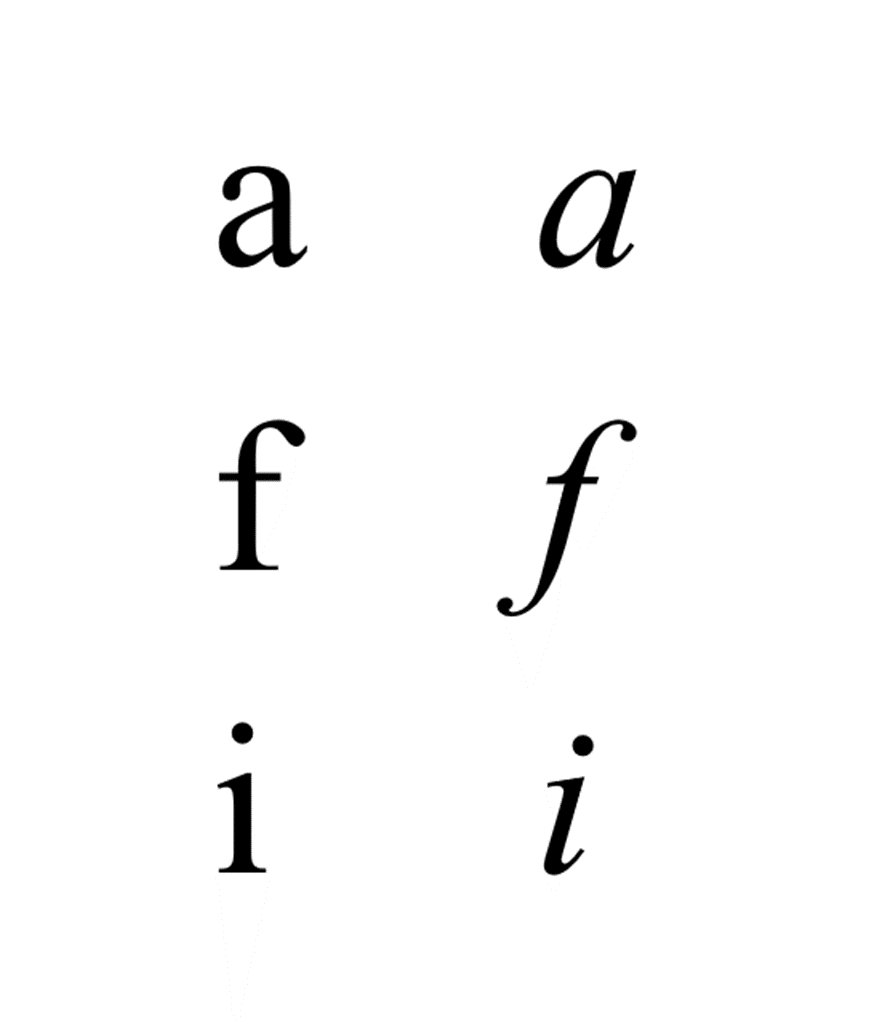

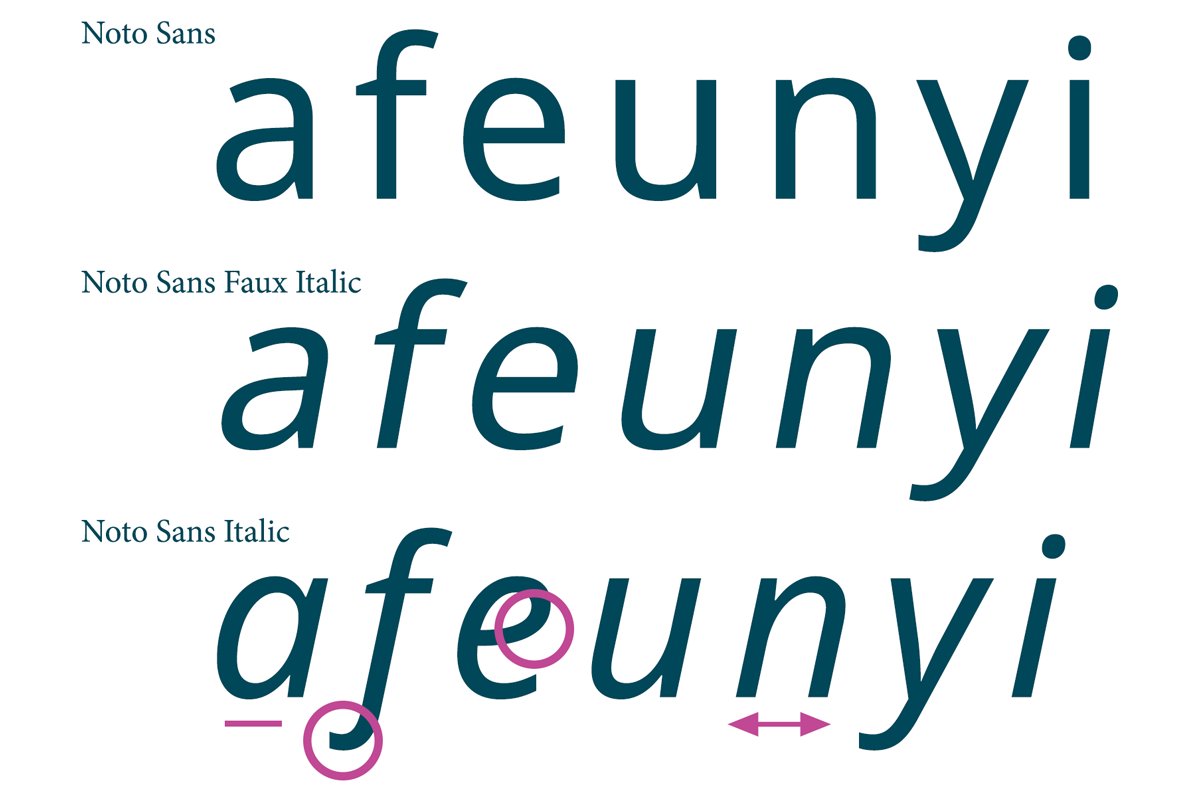

Now here's the typographic catch — not all italics are "true italics".

Griffo didn't just take Roman letters and slant them; he redesigned and reshaped them in a way suited to their new inclination.

Proper italics are always different from the "normal" version of that font.

Griffo didn't just take Roman letters and slant them; he redesigned and reshaped them in a way suited to their new inclination.

Proper italics are always different from the "normal" version of that font.

Loading suggestions...