Kwame Nkrumah believed in creating a United States of Africa with states that would serve each other with “all the necessary economic conditions of labour, of skills, of capital, of minerals, of energy reserves—to provide a self-contained economy”.

As a student in the US, Nkrumah had roamed and worked the streets of New York City. He knew America and applied lessons from its history, where thirteen colonies revolted and formed a union, culminating in the 50 states of the USA.

Nkrumah insisted that Ghana's independence was meaningless unless it was linked to the total liberation of the African continent. Liberation would stretch from north to south. “The Sahara no longer divides us. It unites us”, he said.

Even though his country achieved independence from British occupation in 1957, Nkrumah believed that the freedom struggle needed to incorporate all of Africa, including many areas where violence and colonial exploitation were still tolerated and unchecked.

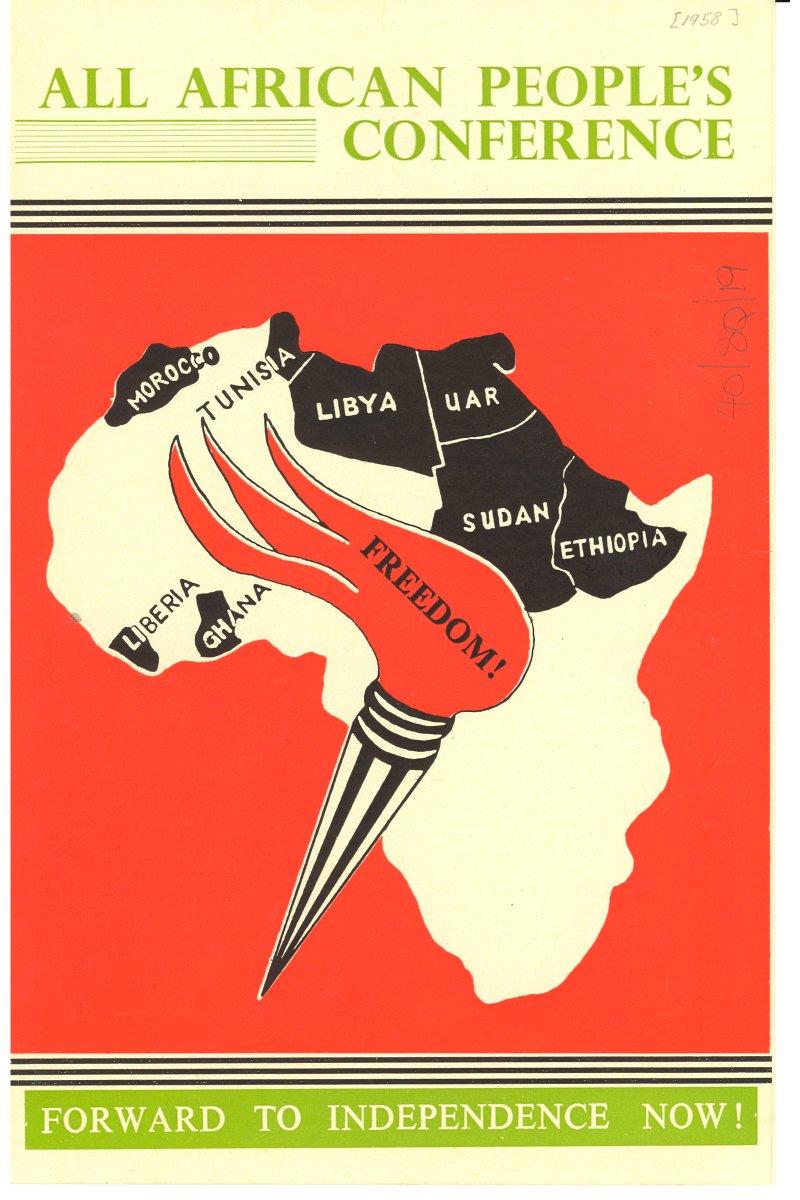

The theme of the first-ever pan-African Conference was “Hands Off Africa! Africa Must Be Free!" and was inspired by a speech Nkrumah gave eight months earlier, at the closing of the Conference of Independent African States, also held in Accra.

The earlier conference was attended by the eight independent states of Africa—Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, and the United Arab Republic (Syria and Egypt). Here, they decided to hold a pan-African Conference “to put meat on the bones”.

Notices were sent out to call Africans to the conference: “Peoples of Africa, Unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains! You have a continent to regain! You have freedom and human dignity to attain!”

Over three hundred political and trade union leaders from 28 African territories responded. Delegates and fraternal observers from Canada, China, India, Indonesia, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, the USA, Britain and other European countries also came.

Delegates started to arrive in Accra on Friday, 5 December. “The atmosphere in our part of Africa was quite intoxicating”, wrote Cameron Duodu of Radio Ghana. Apart from Independence Day the year before, he could not recall a day that excited Ghanaians more.

Many of the delegates knew each other, at least by reputation. One man was unknown to most delegates—Patrice Emery Lumumba from the Belgian Congo. He was the president of the newly established Mouvement National Congolais (MNC).

When Nkrumah arrived, people lined the side of the road carrying placards bearing slogans such as “Ne Touchez Pas l’Afrique’ and “Welcome Africa’s freedom fighters”. On either side of the road were the flags of the nine independent African countries.

Tom Mboya, a 28-year-old Kenyan trade unionist and the Conference chairman, spoke first: “This is a historic occasion. I am sure that all who are here will recognise the significance of it”. He said he had “no doubt” that the two hundred million people of Africa were represented.

Mboya contrasted this conference and a conference 74 years earlier in Europe: the Berlin Conference, where Europeans met to partition Africa. That meeting was known as the “scramble for Africa’. But today, Mboya declared, Europeans “will now decide to scram from Africa”.

In his address, Nkrumah remarked that the gathering marked “the opening of a new epoch”. Never before had it been possible for African freedom fighters to assemble in a free, independent African state to “plan for a final assault upon imperialism and colonialism”, he said.

Nkrumah set out his vision of the liberation and unity of the African continent: “This coming together will evolve eventually into a Union of African States just as the original thirteen American Colonies have now developed into the 49 states constituting the American community”

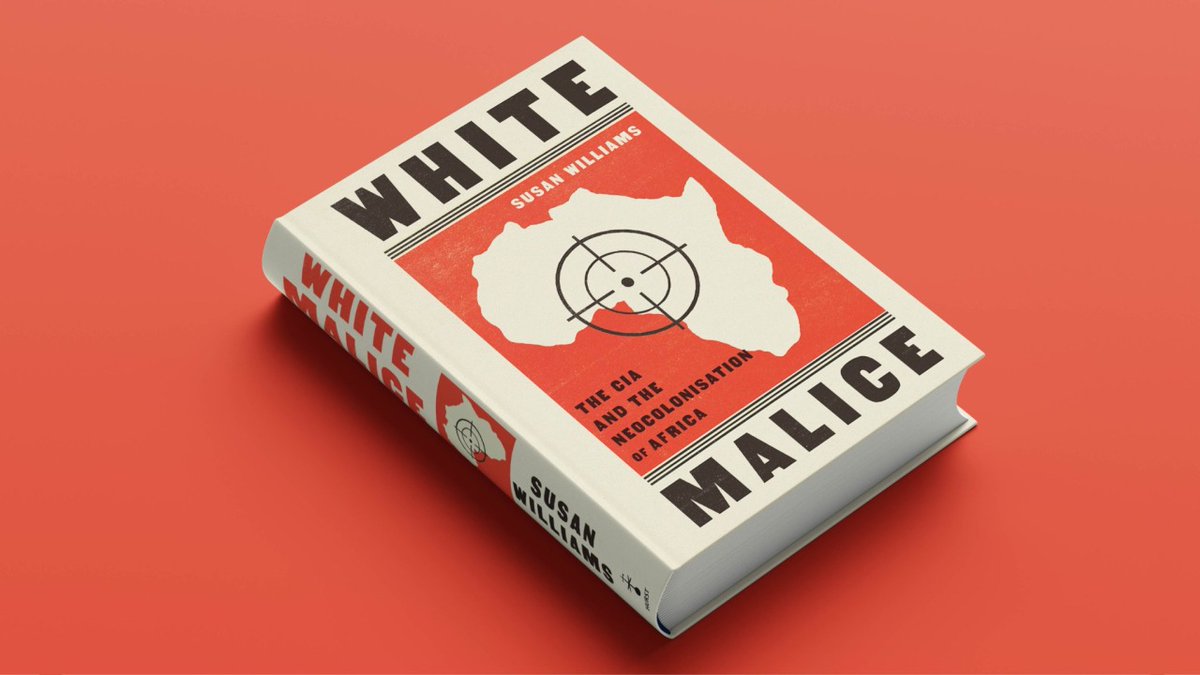

But Nkrumah added a warning: “Do not let us also forget that colonialism and imperialism may come to us yet in a different guise—not necessarily from Europe”. Many understood this to be about the US, while Americans and Britons insisted it was about the Soviets or the Chinese.

Nkrumah ended his address emphatically: “All Africa shall be free in this, our lifetime. This decade is the decade of African independence. Forward then to independence. To Independence Now. Tomorrow, the United States of Africa. I salute you!”.

To underline Nkrumah's point, messages were received from the USSR, China, E. Germany, Bulgaria, N. Korea, Yugoslavia & N. Vietnam. But no greeting arrived from the US. This disappointed some who expected American support because the US itself had supposedly fought colonial rule.

Joshua Nkomo, a freedom fighter from Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), was profoundly moved. Nkrumah, he said, was “one of the most inspiring orators” he had ever heard.

E'skia Mphahlele, a South African who had been forced into exile and was a lecturer at the University College, Ibadan in Nigeria noted that Nkrumah spoke “with restrained impetuosity” as he warned the imperialists “to pack up voluntarily rather than be forced out”.

In the months before the conference the British in Ghana had been communicating with the British colonial administrations in Africa, concerned about potential “embarrassing political and security consequences" that might result from the “subversive” conference.

Many of the delegates faced obstacles getting to the conference. Some were there with a price on their head and snuck out of their countries. Still, Africans from the east, west, north, and south were meeting for the first time.

Numerous delegates had culture shock. They were so different from other Africans in terms of approach, in terms of their language, in terms of attitudes. But the common denominator was that they were meeting in an independent African country.

Some people had been invited, but many just came. They arrived from Nyasaland (Malawi) via the Congo. The police would call the organisers to tell them that some people had arrived saying “We’ve got no documents, this is our land. What’s all this about needing a passport?”

The organisers needed enlightened policemen who would know not to enforce the regulations too strictly. T Ras Makonnen remarked, “The message of independence had gone out. The call had gone to near and far, and the various groups had just set out to come to ‘Rome’”.

For West Africans, it was easy to find their way to Accra. However, the southern African delegations needed help. Couriers had to go to places like Lesotho and Zambia [then the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia] to help with passports.

Among the delegates were prominent freedom fighters including Kenneth Kaunda of Northern Rhodesia, who went on to become the founding president of independent Zambia in 1964; Hastings Banda of Nyasaland, who became the premier of independent Malawi in the same year.

Other freedom fighters included Dr Félix-Roland Moumié of French-ruled Cameroon, A R Mohamed Babu from British-occupied Zanzibar and Frantz Omar Fanon, who led a delegation of the National Liberation Front, which was fighting a bloody war for freedom in Algeria against France.

For Patrice Lumumba, the Conference was a previously undreamed-of opportunity to meet thinkers from all over Africa. He was frequently in the company of the medical doctors Fanon and Moumié. Many were impressed by his energy and enthusiasm for Pan-Africanism.

Frantz Fanon used his speech as an opportunity, for the very first time in public, to make the case for using violence to resist colonialism. This would challenge the commitment to Gandhian nonviolence, which so far had been the hallmark of the conference.

However regrettable the use of violence, Fanon insisted it had to remain an option. He gave a disturbing account of the atrocities carried out against Algerians by the French, arguing that freedom fighters in Africa could not rely on peaceful negotiations alone.

About Fanon's speech, E'skia Mphahlele mused: “He does not mince words. What FLN man can afford the luxury anyway? Algerians have no other recourse but fight back, he says, and the FLN means to go through with it”.

Fanon’s speech took the Conference by storm: he got the loudest and longest ovation of all the speakers. One delegate noted that Fanon succeeded in changing the Conference’s theme from “non-violent” liberation struggle to struggle “by any means”.

After Fanon's speech, Tom Mboya, the chairman, told journalists that there were scenarios in which it was necessary to retaliate. “African leaders at this Conference are not pledged to any pacific policies. They are not pacifists. If you hit them, they might hit back”.

On the same day as Fanon's speech, there was another dramatic development. Alfred Hutchinson of the African National Congress of South Africa suddenly—and unexpectedly—showed up. He had been one of the accused of high treason by the Apartheid state in the Treason Trial.

When charges against him were dropped Hutchinson left South Africa immediately, without a passport to Ghana. He assumed the identity of a migrant mineworker travelling home. After a two-month harrowing journey, he finally arrived in Accra.

The delegates were overjoyed. Hutchinson walked in, “just like one of those outlaws on the screen who come to tame and civilise a noisy, lawless town of the Wild West”, wrote Mphahlele, who was on the platform and had rushed down to embrace the surprise guest.

Kenyan academic Julius Gikonyo Kiano went up to the stage. As he walked, many in the audience lifted banners: “Free Kenyatta now!” Kiano demanded the immediate release of anticolonial leader Jomo Kenyatta. After Kiano's speech, the audience rose to its feet with cries of support.

It was Nigerian Anthony Enahoro who changed the tone, the first real sign of a blemish. It would not be realistic, he said, to expect support for a United States of Africa from every African nation. The Liberians, speaking in a strong American accent, agreed.

When Lumumba addressed the conference, he said it had revealed that despite the borders and ethnic differences, Africans had “the same awareness, the same soul plunged day and night in anguish, the same anxious desire to make this African continent a free and happy continent”.

“To all those who resort to non-violence and civil disobedience, as well as to all those who are compelled to retaliate against violence to attain freedom. The Conference condemns all legislations which consider those who fight for their freedom as ordinary criminals”.

Cameron Duodu wrote years later, “Fanon’s victory in Accra had been total. He had liberated the minds of all African freedom fighters who had previously entertained qualms about the use of violence to liberate their countries”.

On the last day of the Conference, the resolutions were read out. One of the main ones addressed the use of violence brought to the table by Frantz Fanon. It took a pragmatic approach, declaring its full support to all fighters for independence and freedom in Africa:

A key resolution was to form a permanent secretariat based in Accra. This office would endorse nonalignment and positive neutrality: “We are not inclined to the East nor the West. Africa must be friendly but always maintaining and safeguarding her independence”, said Mboya.

Nkrumah gave the final talk. To Africans from the Diaspora, he expressed appreciation: “We must never forget that they are part of us. These sons and daughters of Africa were taken away from our shores...many have made no small contribution to the struggle for African freedom”.

One of the organisers asked the audience to sing “Nkosi Sikelel’ i’Afrika” and “Morena Boloka Sechaba”. Pointing to the map of Africa on the wall, he asked them to respond “Mayibuye!”.

Loading suggestions...