Another long post on the economics of agriculture in India (with inputs from my buddy Frank)

Frank made a profoundly insightful observation. He posited that even with the elimination of all land ceiling laws in India and a significant increase in subsidies, no Indian state (as a matter of fact, no other country in the world) can hope to compete with Russia and Argentina in the international grains market, especially in Central Asia and gulf. Upon conducting a thorough analysis, I was astounded by the clarity and significance of his insight.

While India procures wheat at a Minimum Support Price (MSP) of Rs. 2275 per quintal, Argentina and Russia export wheat at significantly lower prices of Rs. 1994.40 and Rs. 1869.75 per quintal respectively. Furthermore, the spot price of wheat on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) stands at Rs. 1809.92 per quintal in the international market. How can anyone even think about competing in the international market at this rate?

Consider this: the European Union (EU) boasts some of the most generous agricultural subsidies globally, investing substantial resources in this sector. However, despite this significant financial support, European farmers, including those from countries like Poland, find themselves unable to effectively compete with their counterparts from Russia and Ukraine in the grain market. This reality is nothing short of bewildering!

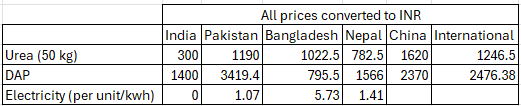

Coming to the subsidies, In India, agricultural subsidies rank among the highest in the region (See the chart below). A comparison of key inputs such as UREA, DAP, and electricity retail prices underscores this reality. Additionally, the government heavily subsidizes capital, with agricultural loans starting at an interest rate as low as 4%. I wanted to compare the cost of capital too with other neighbouring countries but couldn't find sufficient data.

In essence, the debate around #FarmersProtest2024 can be distilled into two pivotal points that individuals on both extremes across the spectrum need to understand:

1) Agriculture, as an industry, inherently relies on significant Government subsidies to remain financially viable. While farm subsidies in India may undergo structural changes over time, they will never vanish entirely. This isn't solely a matter of political expediency; it's a critical issue of national security. Given India's hostile geopolitical landscape, the country cannot afford to rely on imported food, particularly during prolonged conflicts. Consider the recent surge in inflation across the EU and globally, stemming from the supply chain disruptions caused by the Russo-Ukrainian war as a pertinent example.

2) The way things stand, agriculture in India survives due to extensive support from the government. The government of India serves as the primary purchaser of agricultural output and heavily subsidizes virtually every input essential to agriculture — fertilizers, power, capital, machinery, etc.

Frank made a profoundly insightful observation. He posited that even with the elimination of all land ceiling laws in India and a significant increase in subsidies, no Indian state (as a matter of fact, no other country in the world) can hope to compete with Russia and Argentina in the international grains market, especially in Central Asia and gulf. Upon conducting a thorough analysis, I was astounded by the clarity and significance of his insight.

While India procures wheat at a Minimum Support Price (MSP) of Rs. 2275 per quintal, Argentina and Russia export wheat at significantly lower prices of Rs. 1994.40 and Rs. 1869.75 per quintal respectively. Furthermore, the spot price of wheat on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) stands at Rs. 1809.92 per quintal in the international market. How can anyone even think about competing in the international market at this rate?

Consider this: the European Union (EU) boasts some of the most generous agricultural subsidies globally, investing substantial resources in this sector. However, despite this significant financial support, European farmers, including those from countries like Poland, find themselves unable to effectively compete with their counterparts from Russia and Ukraine in the grain market. This reality is nothing short of bewildering!

Coming to the subsidies, In India, agricultural subsidies rank among the highest in the region (See the chart below). A comparison of key inputs such as UREA, DAP, and electricity retail prices underscores this reality. Additionally, the government heavily subsidizes capital, with agricultural loans starting at an interest rate as low as 4%. I wanted to compare the cost of capital too with other neighbouring countries but couldn't find sufficient data.

In essence, the debate around #FarmersProtest2024 can be distilled into two pivotal points that individuals on both extremes across the spectrum need to understand:

1) Agriculture, as an industry, inherently relies on significant Government subsidies to remain financially viable. While farm subsidies in India may undergo structural changes over time, they will never vanish entirely. This isn't solely a matter of political expediency; it's a critical issue of national security. Given India's hostile geopolitical landscape, the country cannot afford to rely on imported food, particularly during prolonged conflicts. Consider the recent surge in inflation across the EU and globally, stemming from the supply chain disruptions caused by the Russo-Ukrainian war as a pertinent example.

2) The way things stand, agriculture in India survives due to extensive support from the government. The government of India serves as the primary purchaser of agricultural output and heavily subsidizes virtually every input essential to agriculture — fertilizers, power, capital, machinery, etc.

Loading suggestions...