In honor of my last day of teaching "Economic Inequality and Growth" at @UCBerkeley, some more graphs.

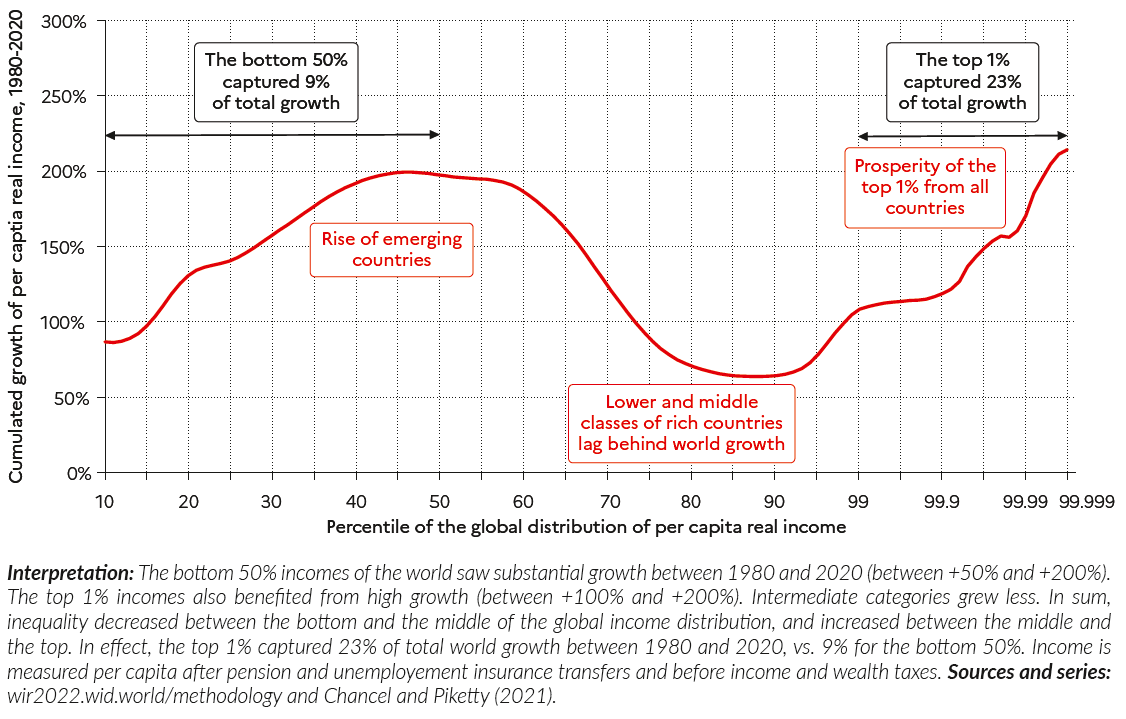

I'll start with the famous elephant curve popularized by @BrankoMilan. Between 1980-2020, most global growth was captured by either the global bottom 50% or the top 1%.

I'll start with the famous elephant curve popularized by @BrankoMilan. Between 1980-2020, most global growth was captured by either the global bottom 50% or the top 1%.

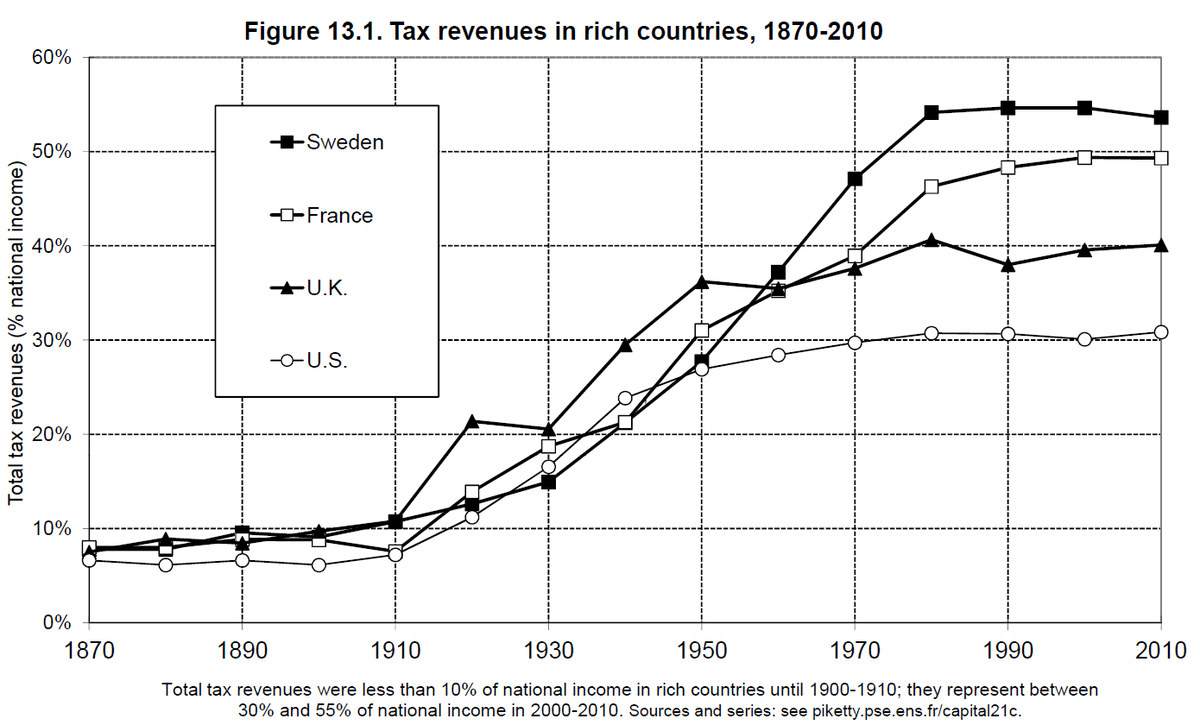

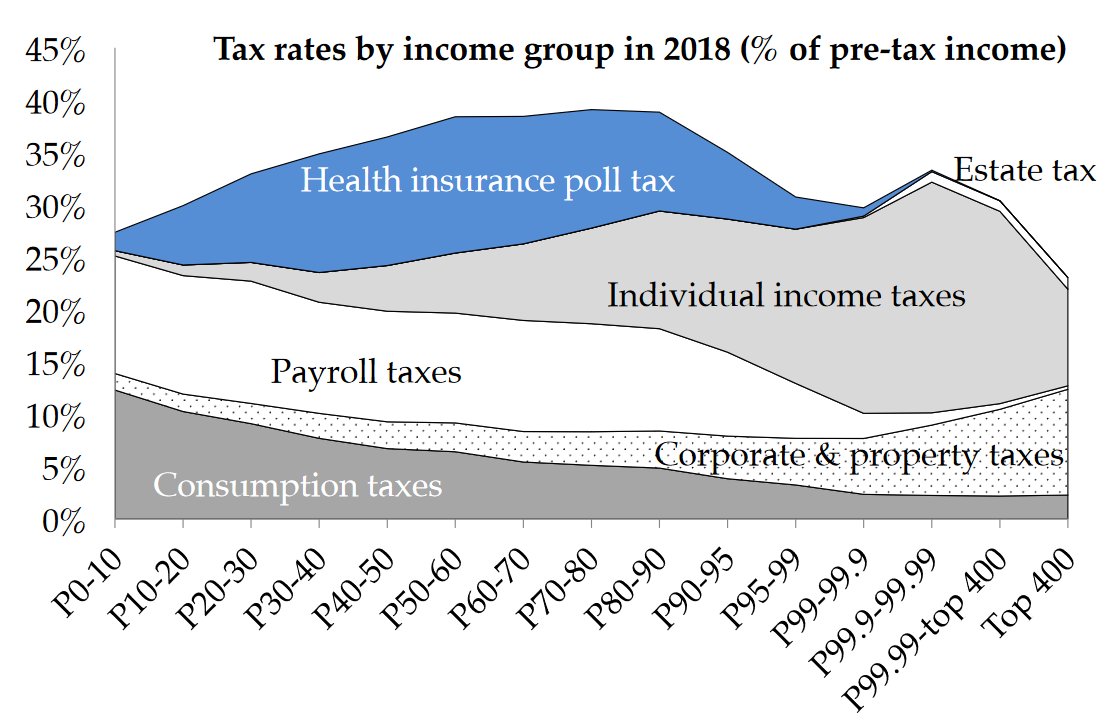

What's hidden in that graph is how tax composition has changed over time. Different taxes have different distributional impacts.

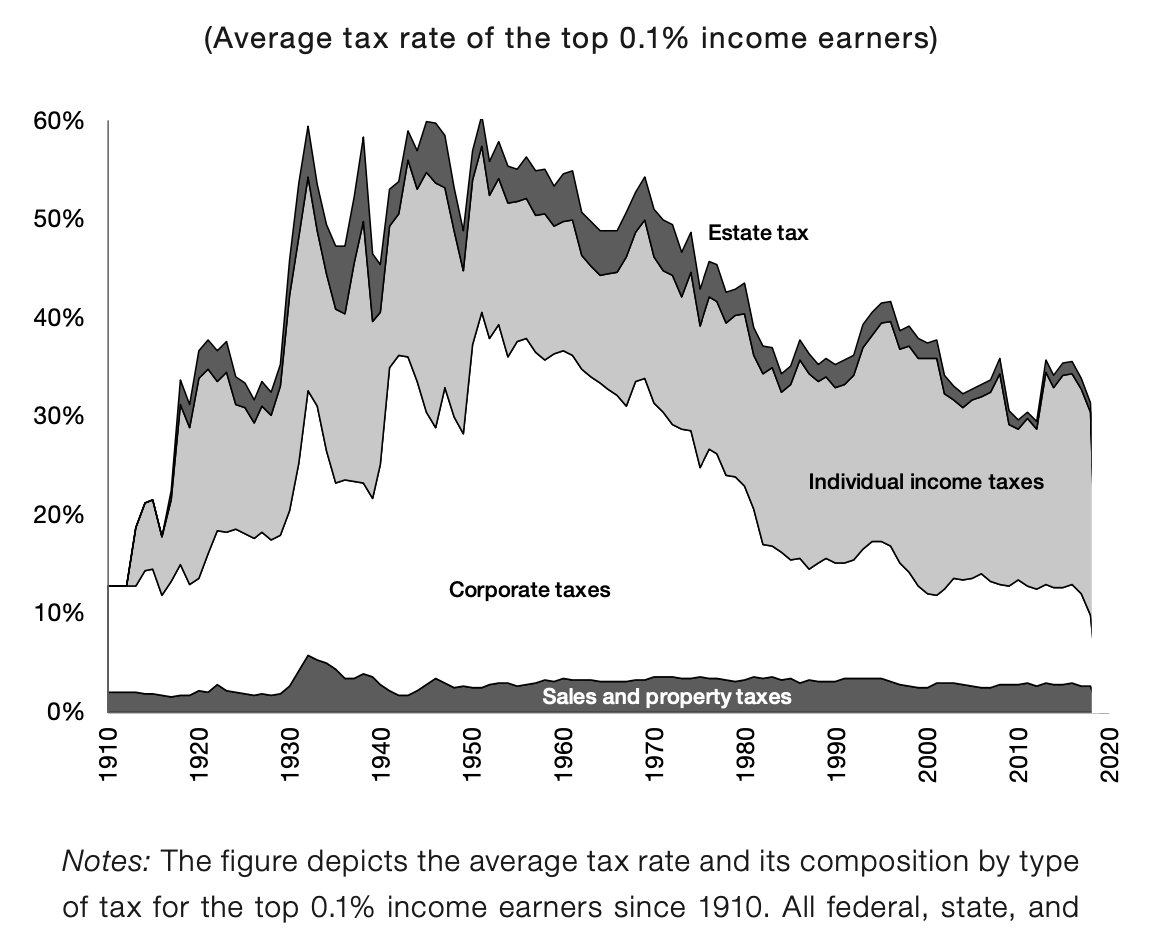

Here are the taxes paid by the top 0.1% in the U.S. from 1910-2020, assuming all corporate tax is paid by firm owners (Saez & @gabriel_zucman 2019).

Here are the taxes paid by the top 0.1% in the U.S. from 1910-2020, assuming all corporate tax is paid by firm owners (Saez & @gabriel_zucman 2019).

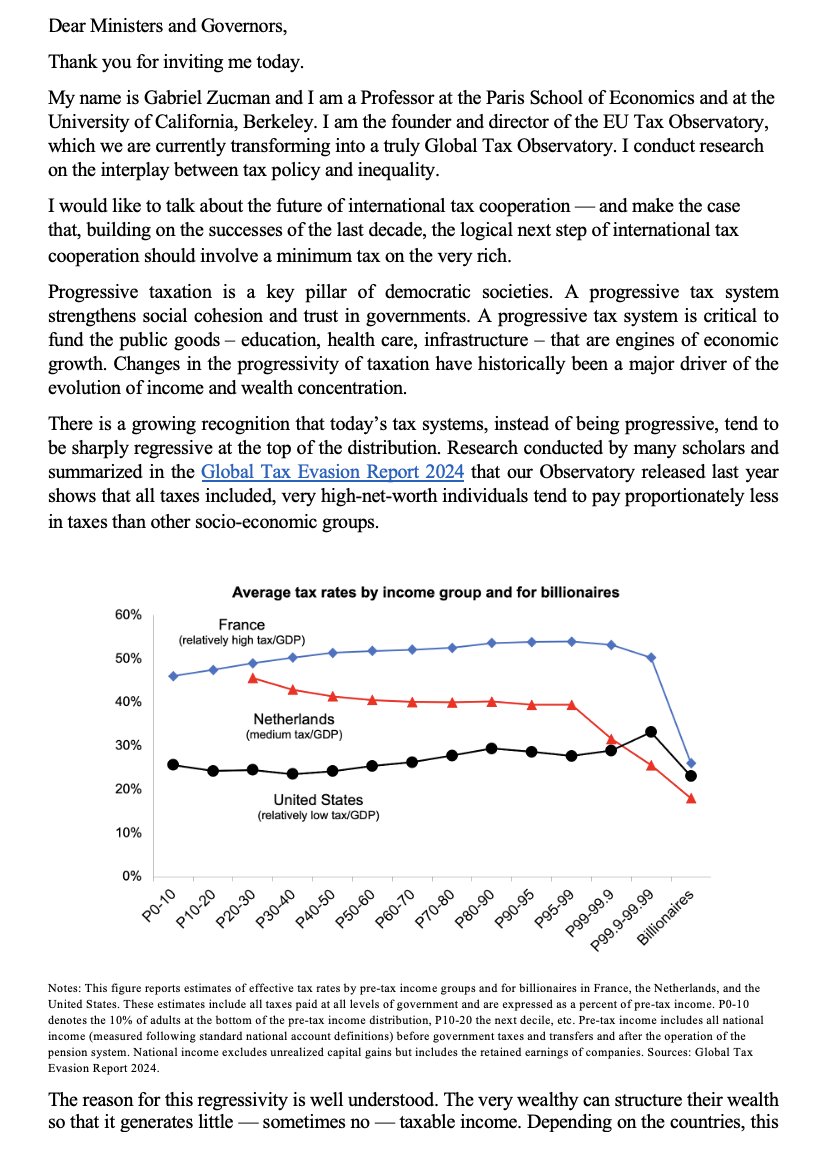

One notable point from the last two graphs is that capital taxes are generally paid by the wealthy.

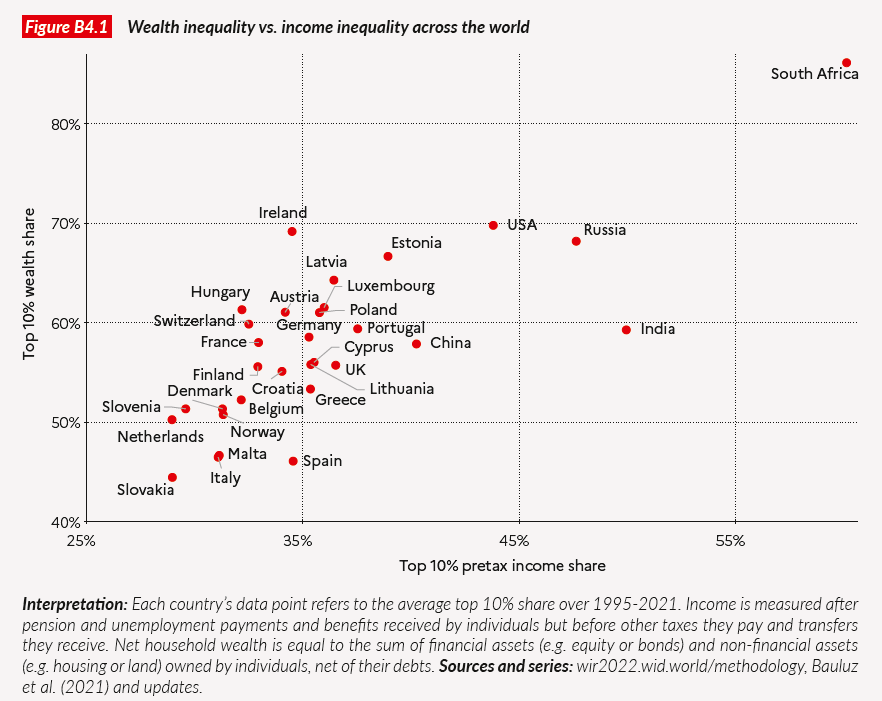

This is intuitive. Capital (wealth) is _always_ more unequally distributed than labor income. Always. Note the axes numbers. @WIL_inequality

This is intuitive. Capital (wealth) is _always_ more unequally distributed than labor income. Always. Note the axes numbers. @WIL_inequality

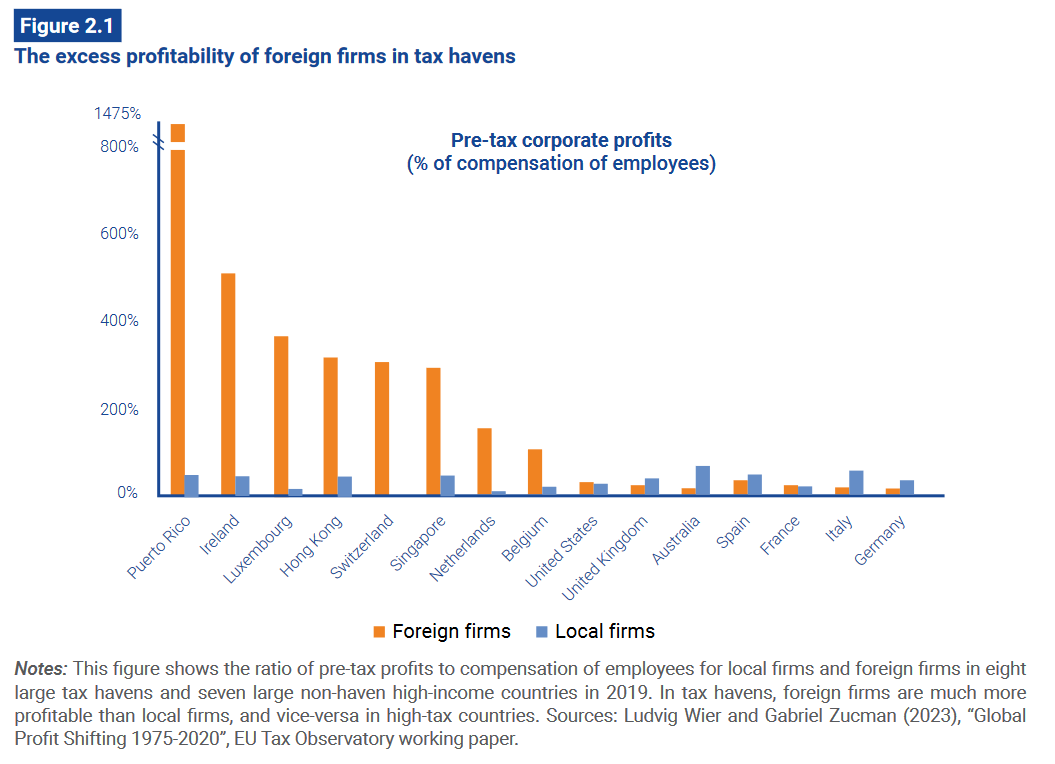

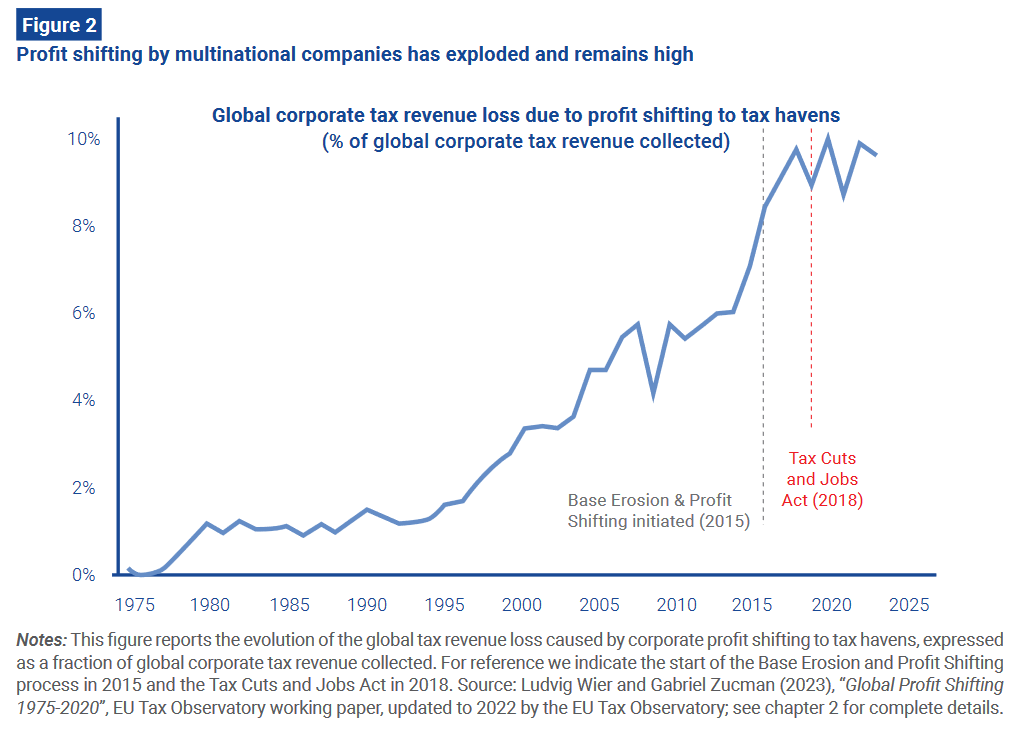

Capital taxation is important, but complicated. Lacking state enforcement and global cooperation has created glaring loopholes.

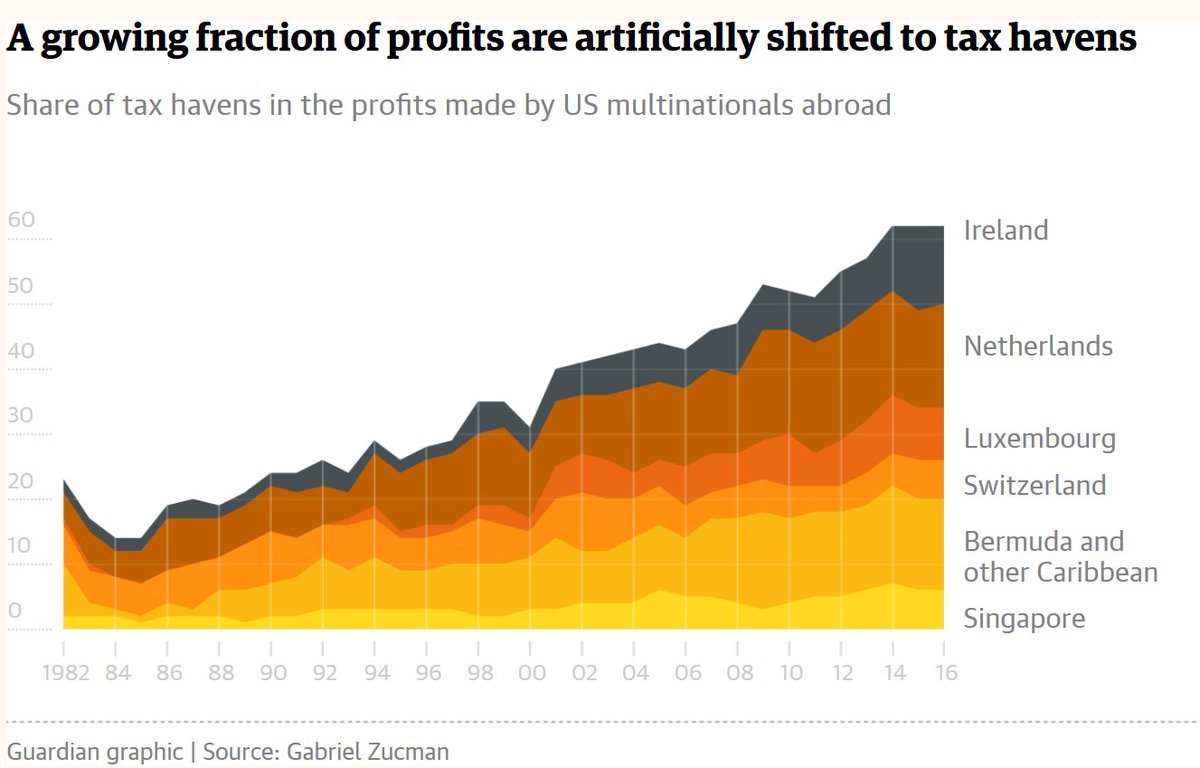

An increasing fraction of US profits are artificially shifted to tax havens. In 2016, the share was ~60% (@gabriel_zucman)

An increasing fraction of US profits are artificially shifted to tax havens. In 2016, the share was ~60% (@gabriel_zucman)

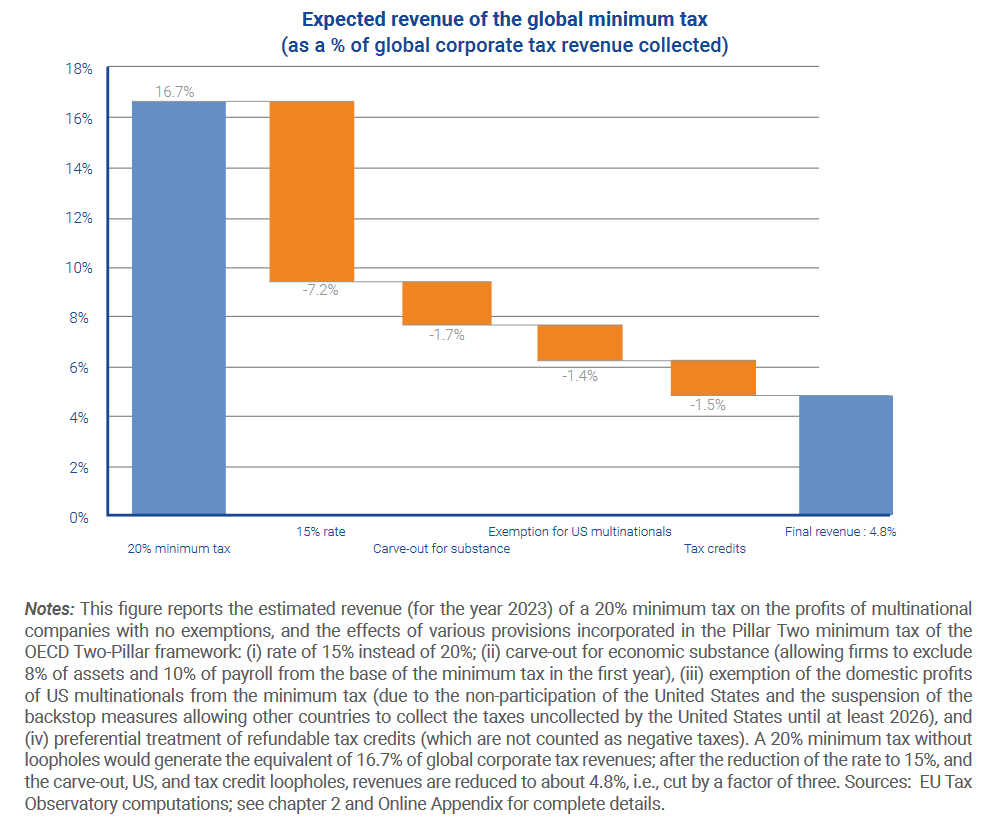

This might change, though. A 15% global minimum corporate income tax was recently agreed upon by 141 @OECD countries.

It could be higher, and exemptions could be reduced, but it's a good start.

It could be higher, and exemptions could be reduced, but it's a good start.

Loading suggestions...