INFLATION & THE PERILS OF PRICE-DEPENDENT GROWTH

Digesting this recent set of news on consumer price push-back in situations like $MCD, $SBUX and $MDLZ has had me thinking about a very basic & critical construct when it comes to analyzing businesses: how much of the growth is coming from volume and how much is coming from price?

This is a very basic distinction, but one that has serious implications for stock selection. Let's discuss.

Surprisingly, disaggregation of revenue growth is a dynamic that the market often seems to misunderstand, in my opinion, and a dimension that the sell-side tends to under-emphasize (despite this criticality of this distinction).

Let me give you an example.

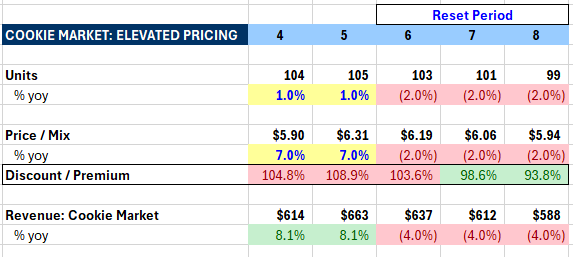

Say I have a cookie market. In equilibrium, volumes grow 1% and price/mix grows 3% to drive 4% mature market-level growth.

Now let's say I have an individual player in that market who is starting at the enviable position of being a quality player at a discount to market level pricing.

This management team sees an opportunity to raise prices (scapegoating broader inflation...), and starts to take price/mix from $4.50 to $6.31 over 5 years. The market loves this, as the market sees elevated revenue growth and likely margin expansion (as 1% of pricing flows through directly to margins).

The market does it's extrapolation dance, applying a peak multiple on peak margins, implicitly assuming that this growth will continue.

In my experience, P/E multiples tend to be influenced by current fundamentals (business momentum, estimate revisions, perception of fundamental growth algorithm). So as the pricing cycle happens, fundamentals accelerate, the company beats & raises estimates, the stock works and everyone is happy. Management gets a pat on the back for "all time record profits".

The reality, however, is that pricing driven growth is inherently less durable than volume driven growth. Pulling the pricing lever in a business is a dangerous game, and one that can backfire (as it seems we are seeing in some certain instances right now).

Without knowing the specifics of these companies, it is easy to see that the COVID-era inflation shock has been a meaningful boon to a group of inflation-exposed consumer goods companies ($KR, $MCD, $MDLZ, $SBUX, $CMG). On average, FCF dollars are up 78% from 2019 to 2023.

While the headlines in many of these companies is "inflation made me do it", we can easily observe that these companies actually benefitted quite materially from the inflation shock we have seen, in some cases not only enhancing $ margin but also % margin.

This risk comes when you violate the pricing umbrella in an industry, however, and push the envelope too far. Specifically, the WSJ reported today that fast food prices in March were 33% higher than 2019 levels, according to the Labor Department. Is this too much?

Broadly, inflation-adjusted consumer incomes are showing tepid growth. The aggregate wallet isn't growing, and so there is a natural point of pushback in consumer pricing decisions. In addition, corporate competitive theory dictates that when ROICs expand without a concurrent increase in return defensibility, competitive response from either new or existing entrants intensifies, leading to pressure normalizing margins & ROIC back to equilibrium.

Digesting this recent set of news on consumer price push-back in situations like $MCD, $SBUX and $MDLZ has had me thinking about a very basic & critical construct when it comes to analyzing businesses: how much of the growth is coming from volume and how much is coming from price?

This is a very basic distinction, but one that has serious implications for stock selection. Let's discuss.

Surprisingly, disaggregation of revenue growth is a dynamic that the market often seems to misunderstand, in my opinion, and a dimension that the sell-side tends to under-emphasize (despite this criticality of this distinction).

Let me give you an example.

Say I have a cookie market. In equilibrium, volumes grow 1% and price/mix grows 3% to drive 4% mature market-level growth.

Now let's say I have an individual player in that market who is starting at the enviable position of being a quality player at a discount to market level pricing.

This management team sees an opportunity to raise prices (scapegoating broader inflation...), and starts to take price/mix from $4.50 to $6.31 over 5 years. The market loves this, as the market sees elevated revenue growth and likely margin expansion (as 1% of pricing flows through directly to margins).

The market does it's extrapolation dance, applying a peak multiple on peak margins, implicitly assuming that this growth will continue.

In my experience, P/E multiples tend to be influenced by current fundamentals (business momentum, estimate revisions, perception of fundamental growth algorithm). So as the pricing cycle happens, fundamentals accelerate, the company beats & raises estimates, the stock works and everyone is happy. Management gets a pat on the back for "all time record profits".

The reality, however, is that pricing driven growth is inherently less durable than volume driven growth. Pulling the pricing lever in a business is a dangerous game, and one that can backfire (as it seems we are seeing in some certain instances right now).

Without knowing the specifics of these companies, it is easy to see that the COVID-era inflation shock has been a meaningful boon to a group of inflation-exposed consumer goods companies ($KR, $MCD, $MDLZ, $SBUX, $CMG). On average, FCF dollars are up 78% from 2019 to 2023.

While the headlines in many of these companies is "inflation made me do it", we can easily observe that these companies actually benefitted quite materially from the inflation shock we have seen, in some cases not only enhancing $ margin but also % margin.

This risk comes when you violate the pricing umbrella in an industry, however, and push the envelope too far. Specifically, the WSJ reported today that fast food prices in March were 33% higher than 2019 levels, according to the Labor Department. Is this too much?

Broadly, inflation-adjusted consumer incomes are showing tepid growth. The aggregate wallet isn't growing, and so there is a natural point of pushback in consumer pricing decisions. In addition, corporate competitive theory dictates that when ROICs expand without a concurrent increase in return defensibility, competitive response from either new or existing entrants intensifies, leading to pressure normalizing margins & ROIC back to equilibrium.

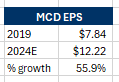

This trend has been great for $MCD profits (FCF +56% and margins up 340bps 2019 to 2024). But the question for the analyst covering the stock is: how durable is this growth?

Again without knowing the specifics at $MCD, what we see is a company who has grown EPS 56% over 4 years, riding the wave of this inflation-encouraged pricing reset. The business is now at 10 year peak margins with a P/E multiple still above the 20-year average (21.4x NTM). Caveat - do your own work here, this is not a stock recommendation, simply an observation.

The unfortunate reality is that when companies get to a point of uncompetitive pricing, the reset period can be painful. Volumes tend to erode. The promotional period can be painful, pressuring revenue as well as gross margins and operating margins. And, depending on the duration of the positive pricing cycle, the negative pricing cycle can last a while.

Inevitably, management will blame "the consumer" or the "economy". Consider these explanations with a skeptical disposition and dig a layer deeper.

To get back to competitive pricing, my hypothetical cookie company may have to deal with 3+ years of pricing reset and multiple years of negative revenue growth (and likely margin compression) - surely a sustained headwind to the stock. Stocks tend to dislike declining revenues and compressing margins.

As a healthcare investor, I lived through the ups & downs of a very dramatic pricing cycle in generic pharma from 2013-2019. It was a party on the way up, and very, very painful on the way down (made more so by the leverage in the balance sheets). Not to imply the consumer goods cycle will even approach that magnitude.

Please don't take this note as a recommendation on any stock, and I am not implying any of these stocks here are longs or shorts (I haven't done the work on any of them recently) but I do want to leave you with a few thoughts.

1) Pricing driven growth seems like a bonanza when it is happening, but is fundamentally riskier growth than volume-driven growth, with greater risk of unravel / reversal

2) When value-prop & price gaps / price umbrellas are violated, it can lead to a challenging period for corporate fundamentals - enhancing risk of volume declines, promotional driven pricing resets and margin compression. Often these are multi-year, not multi-quarter resets

3) The market & the sell-side tend not to see this nuance, thus it is incumbent on buy-side to dig deeply on these topics. Where you can, disaggregate volume & pricing in your revenue build. Corporate disclosures are not always so supportive to this analysis, so the analysis stack will often require creativity (pulling in government data, consumer surveys, assumptions on assumptions, field research / private competitors, etc.)

Hope this is helpful!

Brett

Again without knowing the specifics at $MCD, what we see is a company who has grown EPS 56% over 4 years, riding the wave of this inflation-encouraged pricing reset. The business is now at 10 year peak margins with a P/E multiple still above the 20-year average (21.4x NTM). Caveat - do your own work here, this is not a stock recommendation, simply an observation.

The unfortunate reality is that when companies get to a point of uncompetitive pricing, the reset period can be painful. Volumes tend to erode. The promotional period can be painful, pressuring revenue as well as gross margins and operating margins. And, depending on the duration of the positive pricing cycle, the negative pricing cycle can last a while.

Inevitably, management will blame "the consumer" or the "economy". Consider these explanations with a skeptical disposition and dig a layer deeper.

To get back to competitive pricing, my hypothetical cookie company may have to deal with 3+ years of pricing reset and multiple years of negative revenue growth (and likely margin compression) - surely a sustained headwind to the stock. Stocks tend to dislike declining revenues and compressing margins.

As a healthcare investor, I lived through the ups & downs of a very dramatic pricing cycle in generic pharma from 2013-2019. It was a party on the way up, and very, very painful on the way down (made more so by the leverage in the balance sheets). Not to imply the consumer goods cycle will even approach that magnitude.

Please don't take this note as a recommendation on any stock, and I am not implying any of these stocks here are longs or shorts (I haven't done the work on any of them recently) but I do want to leave you with a few thoughts.

1) Pricing driven growth seems like a bonanza when it is happening, but is fundamentally riskier growth than volume-driven growth, with greater risk of unravel / reversal

2) When value-prop & price gaps / price umbrellas are violated, it can lead to a challenging period for corporate fundamentals - enhancing risk of volume declines, promotional driven pricing resets and margin compression. Often these are multi-year, not multi-quarter resets

3) The market & the sell-side tend not to see this nuance, thus it is incumbent on buy-side to dig deeply on these topics. Where you can, disaggregate volume & pricing in your revenue build. Corporate disclosures are not always so supportive to this analysis, so the analysis stack will often require creativity (pulling in government data, consumer surveys, assumptions on assumptions, field research / private competitors, etc.)

Hope this is helpful!

Brett

Loading suggestions...