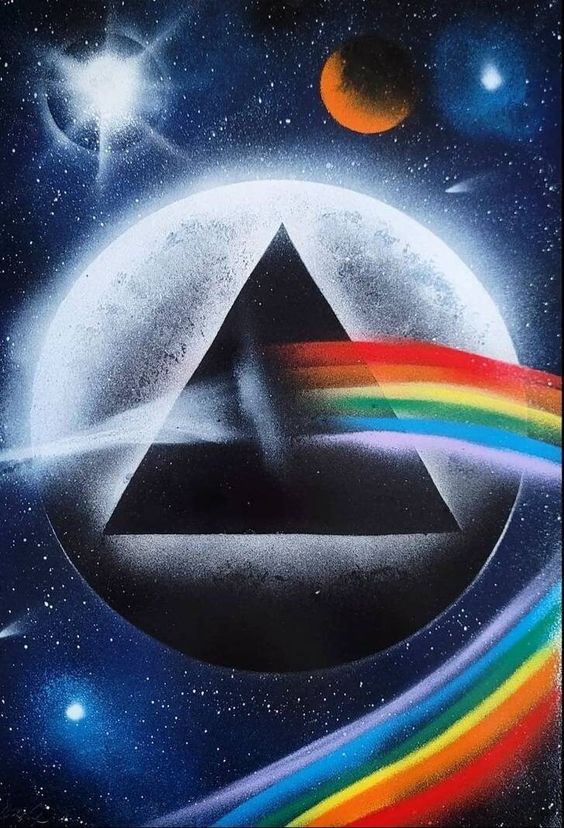

Schrödinger Believed That There Was Only One Mind in the Universe: Quantum Physicist & author of the famous Cat Paradox believed that our individual minds are not unique but rather like the reflected light from prisms.

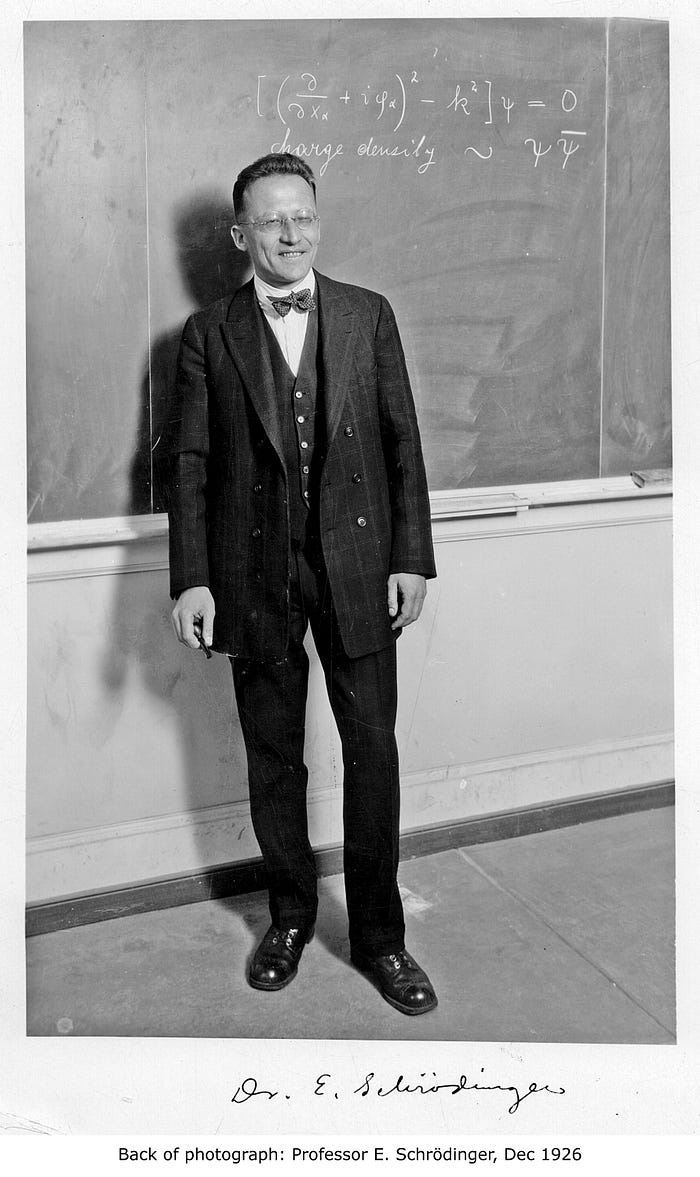

Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger is known for the phrase “The total number of minds in the universe is one. In fact, consciousness is a singularity phasing within all beings.” which best summarizes his philosophical outlook on the nature of reality.

The phrase implies that the apparent multiplicity of minds is just an illusion and that there is only one mind, or one consciousness, that expresses itself in a myriad of ways.

This is what most people describe when they have a near-death experience. Usually, something like "I felt like I was a separate piece, but at the same time joined with everything and a part of one giant entity."

In such a world view, a separation between subject and object does not exist, there is no existence of a subject on the one side and perception of an object on the other. In a world without the subject-object split, we are all an expression of the one.

A thread to split your mind and still you will connected to one universal mind.

Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger is known for the phrase “The total number of minds in the universe is one. In fact, consciousness is a singularity phasing within all beings.” which best summarizes his philosophical outlook on the nature of reality.

The phrase implies that the apparent multiplicity of minds is just an illusion and that there is only one mind, or one consciousness, that expresses itself in a myriad of ways.

This is what most people describe when they have a near-death experience. Usually, something like "I felt like I was a separate piece, but at the same time joined with everything and a part of one giant entity."

In such a world view, a separation between subject and object does not exist, there is no existence of a subject on the one side and perception of an object on the other. In a world without the subject-object split, we are all an expression of the one.

A thread to split your mind and still you will connected to one universal mind.

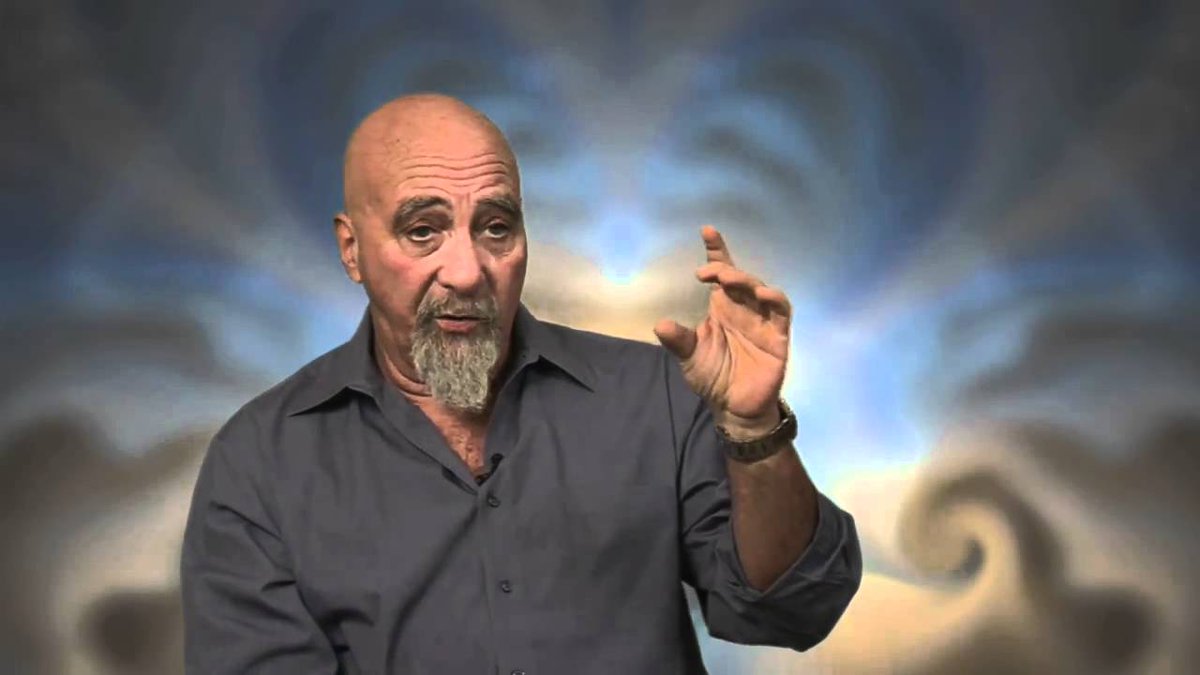

One of the greatest Physicists Donald Hoffman [] & Schrödinger (1887–1961) believed that “The total number of minds in the universe is one.” That is, a universal Mind accounts for everything. [x.com]

In 1925, just a few months before Schrödinger discovered the most basic equation of quantum mechanics, he wrote down the first sketches of the ideas that he would later develop more thoroughly in “Mind and Matter”.

Already then, his thoughts on technical matters were inspired by what he took to be greater metaphysical (religious) questions. Early on, Schrödinger expressed the conviction that metaphysics does not come after physics, but inevitably precedes it. Metaphysics is not a deductive affair but a speculative one.

Credit: iai.tv

In 1925, just a few months before Schrödinger discovered the most basic equation of quantum mechanics, he wrote down the first sketches of the ideas that he would later develop more thoroughly in “Mind and Matter”.

Already then, his thoughts on technical matters were inspired by what he took to be greater metaphysical (religious) questions. Early on, Schrödinger expressed the conviction that metaphysics does not come after physics, but inevitably precedes it. Metaphysics is not a deductive affair but a speculative one.

Credit: iai.tv

From the 1950s on, when Schrödinger ceased to actively work on the physics of his time, he focused more on wider philosophical and ethical issues related to science.

Back then, his conferences always ended with what he jokingly called the “second Schrödinger equation”: “Atman = Brahman”, the Indian doctrine of identity.

Schrödinger said that we make two big assumptions that we can't prove or disprove:

1. There's a world outside our own minds (that exists even when we're not thinking about it).

2. There are many separate minds (like yours and mine).

We can't test these assumptions because we can't step outside our own experiences. But these assumptions create big problems:

1. How do our minds interact with the physical world? (Why does the world seem purely physical and not full of qualities like colors and sounds?)

2. How are our minds different from each other? (Why are we unique individuals?)

Schrödinger thought that we could solve these problems by looking at things differently. He didn't agree with traditional Western ideas (like materialism and idealism), but he found inspiration in Eastern philosophies (like Indian ideas). He believed that there's a simpler way to understand the world and our minds.

Back then, his conferences always ended with what he jokingly called the “second Schrödinger equation”: “Atman = Brahman”, the Indian doctrine of identity.

Schrödinger said that we make two big assumptions that we can't prove or disprove:

1. There's a world outside our own minds (that exists even when we're not thinking about it).

2. There are many separate minds (like yours and mine).

We can't test these assumptions because we can't step outside our own experiences. But these assumptions create big problems:

1. How do our minds interact with the physical world? (Why does the world seem purely physical and not full of qualities like colors and sounds?)

2. How are our minds different from each other? (Why are we unique individuals?)

Schrödinger thought that we could solve these problems by looking at things differently. He didn't agree with traditional Western ideas (like materialism and idealism), but he found inspiration in Eastern philosophies (like Indian ideas). He believed that there's a simpler way to understand the world and our minds.

Inspired by Indian philosophy, Schrödinger had a mind-first, not matter-first, view of the universe. But he was a non-materialist of a rather special kind. He believed that there is only one mind in the universe; our individual minds are like the scattered light from prisms:

A metaphor that Schrödinger liked to invoke to illustrate this idea is the one of a crystal that creates a multitude of colors (individual selves) by refracting light (standing for the cosmic self that is equal to the essence of the universe).

We are all but aspects of one single mind that forms the essence of reality. He also referred to this as the doctrine of identity.

Accordingly, a non-dual form of consciousness, which must not be conflated with any of its single aspects, grounds the refutation of the (merely apparent) distinction into separate selves that inhabit a single world.

“Not only has none of us ever experienced more than one consciousness, but there is also no trace of circumstantial evidence of this ever happening anywhere in the world.”

A metaphor that Schrödinger liked to invoke to illustrate this idea is the one of a crystal that creates a multitude of colors (individual selves) by refracting light (standing for the cosmic self that is equal to the essence of the universe).

We are all but aspects of one single mind that forms the essence of reality. He also referred to this as the doctrine of identity.

Accordingly, a non-dual form of consciousness, which must not be conflated with any of its single aspects, grounds the refutation of the (merely apparent) distinction into separate selves that inhabit a single world.

“Not only has none of us ever experienced more than one consciousness, but there is also no trace of circumstantial evidence of this ever happening anywhere in the world.”

Schrödinger drew remarkable consequences from this (in his book Mind and Matter (1958)).

- Every person is the same as every other person who has ever lived.

- There's no real difference between you and someone who lived thousands of years ago.

He asked: "What makes you, YOU, and not someone else?" He didn't think there was any scientific way to answer this question.

Schrödinger believed that there's only one mind in the universe, shared by everyone. He thought this because:

- We only ever experience one consciousness at a time (our own).

- There's no evidence that anyone has ever experienced multiple consciousnesses.

He compared this idea to John Wheeler's idea that there's only one electron in the universe. Schrödinger thought that just as all electrons are the same, all minds are the same too.

- Every person is the same as every other person who has ever lived.

- There's no real difference between you and someone who lived thousands of years ago.

He asked: "What makes you, YOU, and not someone else?" He didn't think there was any scientific way to answer this question.

Schrödinger believed that there's only one mind in the universe, shared by everyone. He thought this because:

- We only ever experience one consciousness at a time (our own).

- There's no evidence that anyone has ever experienced multiple consciousnesses.

He compared this idea to John Wheeler's idea that there's only one electron in the universe. Schrödinger thought that just as all electrons are the same, all minds are the same too.

Some people might not agree with the ideas presented so far. We started with the idea that the Mind is the most important thing, and that's a common idea throughout history. But then we added that individual minds (like yours and mine) can't think or act independently from the universal Mind. This limits the power of the universal Mind.

It's not clear why the universal Mind couldn't give animals and humans the ability to think and act on their own. Just because we can only experience our own consciousness doesn't mean we're just extensions of the universal Mind.

This idea is especially problematic for humans, who deal with good and evil. If we're all just one mind, then Martin Luther King and Josef Stalin are the same mind, which doesn't make sense. Humans can choose to do good or bad things, which can't be explained by just being different parts of a spectrum.

It's not clear why the universal Mind couldn't give animals and humans the ability to think and act on their own. Just because we can only experience our own consciousness doesn't mean we're just extensions of the universal Mind.

This idea is especially problematic for humans, who deal with good and evil. If we're all just one mind, then Martin Luther King and Josef Stalin are the same mind, which doesn't make sense. Humans can choose to do good or bad things, which can't be explained by just being different parts of a spectrum.

Your Very Own Consciousness Can Interact With the Whole Universe

A recent experiment suggests the brain is not too warm or wet for consciousness to exist as a quantum wave that connects with the rest of the universe.

Whether we create consciousness in our brains as a function of our neurons firing, or consciousness exists independently of us, there’s no universally accepted scientific explanation for where it comes from or where it lives. However, new research on the physics, anatomy, and geometry of consciousness has begun to reveal its possible form.

In other words, we may soon be able to identify a true architecture of consciousness.

Source: popularmechanics.com

A recent experiment suggests the brain is not too warm or wet for consciousness to exist as a quantum wave that connects with the rest of the universe.

Whether we create consciousness in our brains as a function of our neurons firing, or consciousness exists independently of us, there’s no universally accepted scientific explanation for where it comes from or where it lives. However, new research on the physics, anatomy, and geometry of consciousness has begun to reveal its possible form.

In other words, we may soon be able to identify a true architecture of consciousness.

Source: popularmechanics.com

The Orch OR theory proposes consciousness is a quantum process facilitated by microtubules in the brain’s nerve cells. [by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Roger Penrose, Ph.D., and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff, M.D]

Recently, Hameroff explains your consciousness is like a drop of water that can connect with the entire ocean, and even affect the ocean's waves. This means your consciousness can reach beyond your brain and connect with the universe in a way that's not normally possible.

He suggested that consciousness is a quantum wave that passes through these microtubules. And that, like every quantum wave, it has properties like superposition (the ability to be in many places at the same time) and entanglement (the potential for two particles that are very far away to be connected).

Recently, Hameroff explains your consciousness is like a drop of water that can connect with the entire ocean, and even affect the ocean's waves. This means your consciousness can reach beyond your brain and connect with the universe in a way that's not normally possible.

He suggested that consciousness is a quantum wave that passes through these microtubules. And that, like every quantum wave, it has properties like superposition (the ability to be in many places at the same time) and entanglement (the potential for two particles that are very far away to be connected).

Other scientists thought they could dismiss the idea of quantum consciousness because:

- Quantum coherence (keeping particles connected as a wave) only works in very cold and controlled environments.

- When taken out of that environment, the wave breaks down, and particles become separate and measurable.

- The brain is warm, wet, and messy, so it couldn't possibly maintain quantum coherence.

But then, scientists discovered quantum biology, which shows that:

Living things can use quantum properties even in warm and uncontrolled environments. This means that particles in the brain could potentially connect with the universe, supporting the idea of quantum consciousness.

This video shows the brain’s network of neural axons transmitting electrical action potentials.

- Quantum coherence (keeping particles connected as a wave) only works in very cold and controlled environments.

- When taken out of that environment, the wave breaks down, and particles become separate and measurable.

- The brain is warm, wet, and messy, so it couldn't possibly maintain quantum coherence.

But then, scientists discovered quantum biology, which shows that:

Living things can use quantum properties even in warm and uncontrolled environments. This means that particles in the brain could potentially connect with the universe, supporting the idea of quantum consciousness.

This video shows the brain’s network of neural axons transmitting electrical action potentials.

Timothy Palmer, Ph.D., is a mathematical physicist at Oxford who specializes in chaos and climate. (He’s also a big fan of Roger Penrose.) Palmer believes the laws of physics must be fundamentally geometric. The Invariant Set Theory is his explanation of how the quantum world works. Among other things, it suggests that quantum consciousness is the result of the universe operating in a particular fractal geometry “state space.”

Palmer believes We're part of a cosmic fractal shape that connects different realities. These realities are stuck in their own trajectories, just like us. Our sense of free will and consciousness might come from awareness of these other universes

This idea starts with a concept called a Strange Attractor, which is a special geometry that helps predict how complex systems (like weather) behave. Mathematician Edward Lorenz developed this idea in the 1960s.

Lorenz tried to simplify weather prediction by using just three equations to identify the "state space" of a weather system. He then plotted the trajectory of weather systems by plugging in different initial conditions.

Think of it like a map with many possible paths. Each path represents a different reality, and we're stuck on our own path. But, our awareness of other paths (other universes) might give us the illusion of free will and consciousness.

It's a complex idea, but it suggests that our reality is connected to others in a vast, cosmic web.

Palmer believes We're part of a cosmic fractal shape that connects different realities. These realities are stuck in their own trajectories, just like us. Our sense of free will and consciousness might come from awareness of these other universes

This idea starts with a concept called a Strange Attractor, which is a special geometry that helps predict how complex systems (like weather) behave. Mathematician Edward Lorenz developed this idea in the 1960s.

Lorenz tried to simplify weather prediction by using just three equations to identify the "state space" of a weather system. He then plotted the trajectory of weather systems by plugging in different initial conditions.

Think of it like a map with many possible paths. Each path represents a different reality, and we're stuck on our own path. But, our awareness of other paths (other universes) might give us the illusion of free will and consciousness.

It's a complex idea, but it suggests that our reality is connected to others in a vast, cosmic web.

Palmer believes that our universe may be just one trajectory, one car, on a cosmological state space like the Lorenz attractor. When we imagine “what if …?” scenarios, we’re actually getting information about versions of ourselves in other universes who are also navigating the same strange attractor—others’ “cars” on the track, he explains. This also accounts for our sense of consciousness, of free will, and of being connected with a greater universe.

“I would at least hypothesize that it may well be the case that it’s evolving on very special fractal subsets of all conceivable states in state space,” Palmer tells Popular Mechanics. If his ideas are correct, he says, “then we need to look at the structure of the universe on its very largest scales, because these attractors are really telling us about a kind of holistic geometry for the universe.”

“I would at least hypothesize that it may well be the case that it’s evolving on very special fractal subsets of all conceivable states in state space,” Palmer tells Popular Mechanics. If his ideas are correct, he says, “then we need to look at the structure of the universe on its very largest scales, because these attractors are really telling us about a kind of holistic geometry for the universe.”

Loading suggestions...

![One of the greatest Physicists Donald Hoffman [] & Schrödinger (1887–1961) believed that “The total...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GV2pxrJXAAEqAD7.jpg)