(3/x) Unfortunately, it is not that simple. Here's the approach I use 👇

(this works when trying to optimize someone's hemodynamics with IV fluids, or with interventions like vasopressors or inotropes)

1. Assess microcirculatory function

2. Assess for fluid tolerance

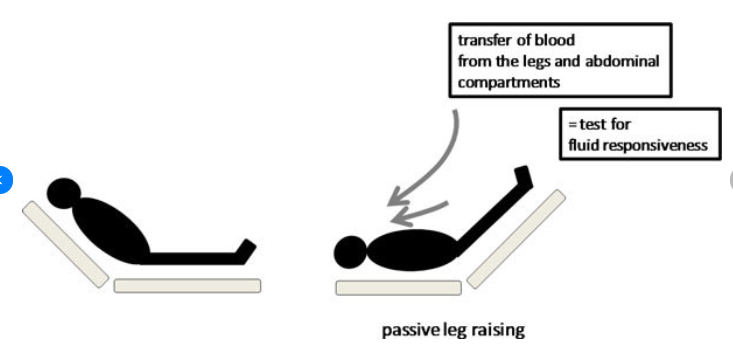

3. Assess for fluid responsiveness

Another way to think of #1 is "Is there a reason to do something in the first place?"

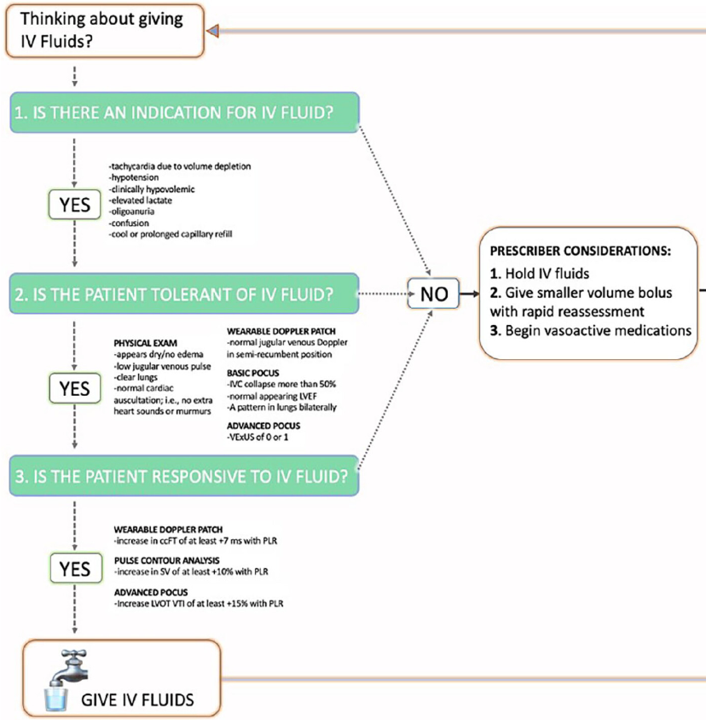

This is summarized nicely in this figure by @khaycock2 et al. journals.sagepub.com

(this works when trying to optimize someone's hemodynamics with IV fluids, or with interventions like vasopressors or inotropes)

1. Assess microcirculatory function

2. Assess for fluid tolerance

3. Assess for fluid responsiveness

Another way to think of #1 is "Is there a reason to do something in the first place?"

This is summarized nicely in this figure by @khaycock2 et al. journals.sagepub.com

(4/x) So why start with assessing perfusion?

If it aint broke, don't fix it!

At this time, YOU are currently:

1) fluid responsive

and

2) fluid tolerant

yet you do not need IV fluid boluses!

Why?

Your end organ perfusion is normal! (presumably...).

The is the first part to hemodynamic mastery; knowing WHEN to be concerned about hemodynamics and when we are just treating the number.

For example.

If you have a patient with low EF and a cardiac index of 1.8 with normal perfusion surrogates, great urine output, who is weaning off vasopressors. Giving an inotropes is unlikely to benefit, as they are not manifesting signs of hypoperfusion.

If it aint broke, don't fix it!

At this time, YOU are currently:

1) fluid responsive

and

2) fluid tolerant

yet you do not need IV fluid boluses!

Why?

Your end organ perfusion is normal! (presumably...).

The is the first part to hemodynamic mastery; knowing WHEN to be concerned about hemodynamics and when we are just treating the number.

For example.

If you have a patient with low EF and a cardiac index of 1.8 with normal perfusion surrogates, great urine output, who is weaning off vasopressors. Giving an inotropes is unlikely to benefit, as they are not manifesting signs of hypoperfusion.

(5/x) So what is the best way to assess microcirculatory function (aka perfusion).

Unfortunately it is challenging to directly assess organ level perfusion --> instead, we rely on surrogates.

I try to integrate as many perfusion surrogates as I can:

1. Cap Refill Time --> increasing evidence. My 1st line.

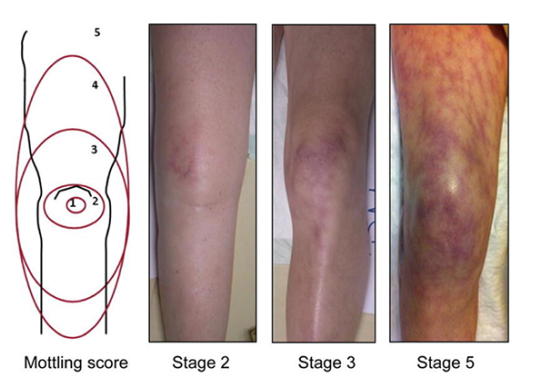

2. Mottling

3. Urine output

4. Altered LOC

5. Poor pleth capture

However.

There is another layer to microcirculatory function we often don't talk about. Hemodynamic coherence. 👇

Unfortunately it is challenging to directly assess organ level perfusion --> instead, we rely on surrogates.

I try to integrate as many perfusion surrogates as I can:

1. Cap Refill Time --> increasing evidence. My 1st line.

2. Mottling

3. Urine output

4. Altered LOC

5. Poor pleth capture

However.

There is another layer to microcirculatory function we often don't talk about. Hemodynamic coherence. 👇

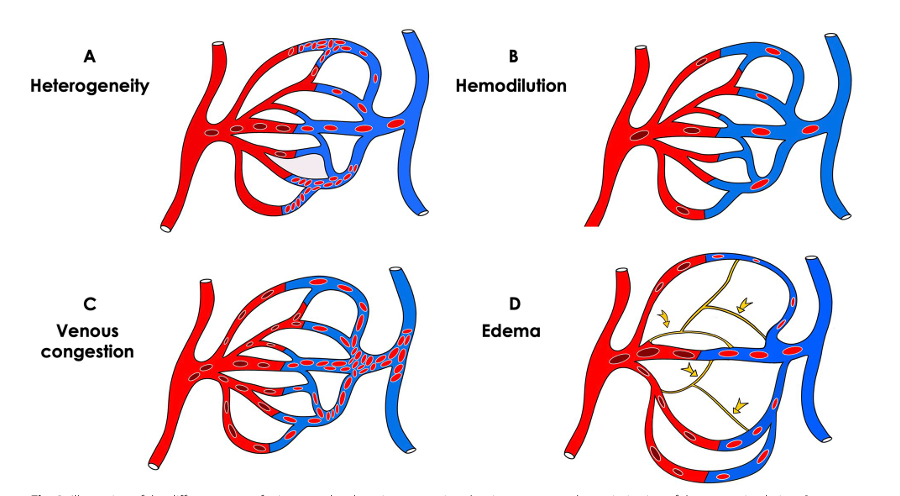

(6/x) Hemodynamic coherence asks whether a hemodynamic intervention like fluids, vasopressors, or inotropes will actually improve perfusion surrogates (or end organ perfusion itself) in patients with poor perfusion.

Now this might seem counterintuitive.

If you have a patient who has poor perfusion, low stroke volume, is fluid responsive, and gets a fluid bolus, surely their perfusion will improve?

Not always.

Early in illness courses more patients are hemodynamically coherent - a hemodynamic intervention will result in improved perfusion.

Later in disease processes due to multiple mechanisms, including tissue congestion and edema, macro-circulatory interventions may not be translated to the micro-circulatory level.

This is hemodynamic incoherence.

For more reading: doi.org

Now this might seem counterintuitive.

If you have a patient who has poor perfusion, low stroke volume, is fluid responsive, and gets a fluid bolus, surely their perfusion will improve?

Not always.

Early in illness courses more patients are hemodynamically coherent - a hemodynamic intervention will result in improved perfusion.

Later in disease processes due to multiple mechanisms, including tissue congestion and edema, macro-circulatory interventions may not be translated to the micro-circulatory level.

This is hemodynamic incoherence.

For more reading: doi.org

(7/x) This begs the question, for a patient who has become hemodynamically incoherent (aka hemodynamic interventions are NOT improving micro-circulation), what should you do?

First, do less.

Repetitive fluid boluses for patients who are hemodynamically incoherent may contribute to the pathophysiology of edema and congestion, and will not be of benefit.

After this we are in an evidence free zone.

I ask "why is my patient hemodynamically incoherent?". If edema or congestion are at play, I will attempt to improve this.

This is a huge area for future research that the bright minds like @AndromedaShock @ArgaizR and more are addressing.

First, do less.

Repetitive fluid boluses for patients who are hemodynamically incoherent may contribute to the pathophysiology of edema and congestion, and will not be of benefit.

After this we are in an evidence free zone.

I ask "why is my patient hemodynamically incoherent?". If edema or congestion are at play, I will attempt to improve this.

This is a huge area for future research that the bright minds like @AndromedaShock @ArgaizR and more are addressing.

(8/x) Really curious - what do you do for patients with hemodynamic incoherence? Does anyone have structured approach to addressing this?

Admittedly, I am only starting to develop a solid framework.

@ArgaizR @AndromedaShock @ThinkingCC @katiewiskar @WBeaubien @john_basmaji @msiuba @PulmCrit

Admittedly, I am only starting to develop a solid framework.

@ArgaizR @AndromedaShock @ThinkingCC @katiewiskar @WBeaubien @john_basmaji @msiuba @PulmCrit

Loading suggestions...