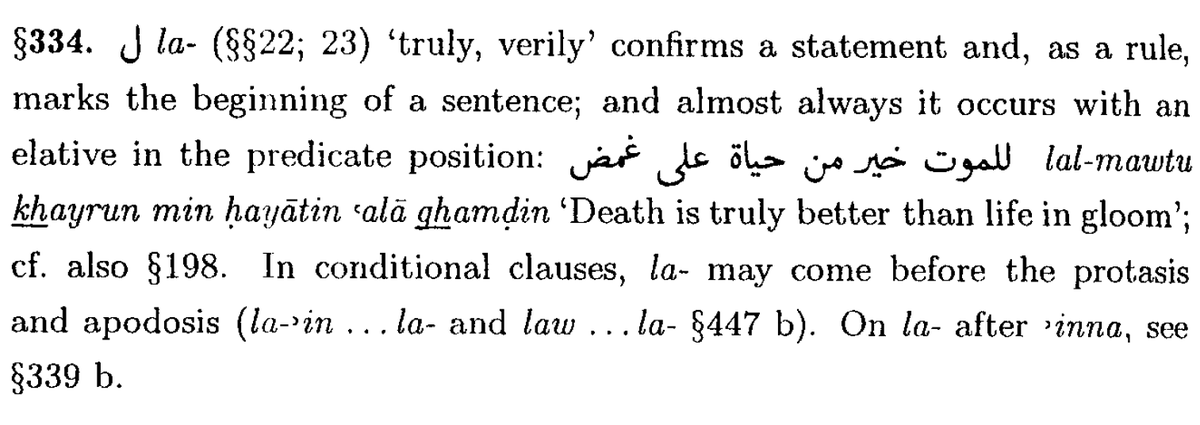

First, it is important to note that there are functionally, and syntactically quite different uses of la-.

First, verbs that end in the energic -an(na) always have an obligatory la- in the Quran, no exceptions.

Q2:96 wa-la-tajid-anna-hum "you will find them"

First, verbs that end in the energic -an(na) always have an obligatory la- in the Quran, no exceptions.

Q2:96 wa-la-tajid-anna-hum "you will find them"

The second use of la- is the apodosis of conditional sentences introduced by law "if (hypothetical)" or lawlâ "if not (hypothetical)".

Such a la- is necessarily phrase-initial and always followed by a verb.

Q2:20 wa-law šāʾa ḷḷāhu la-ḏahaba bi-samʿihim wa-ʾabṣārihim

Such a la- is necessarily phrase-initial and always followed by a verb.

Q2:20 wa-law šāʾa ḷḷāhu la-ḏahaba bi-samʿihim wa-ʾabṣārihim

la- may sometimes also be used as the apodosis to ʾin "if", but this is relatively rare.

But outside of these "obligatory" la-'s which don't really carry meaning on their own, but are just the automatic part of the construction used, things get weirder.

But outside of these "obligatory" la-'s which don't really carry meaning on their own, but are just the automatic part of the construction used, things get weirder.

la- may introduce a conditional sentence, in which case it is placed before ʾin "if". This presumably gives a 'intensifying' meaning to the sentence.

la- can also occur before the future particle sawfa (Q92:21) wa-la-sawfa yarḍā "and verily he will be pleased"

It can also occur before qad + perfect. Q2:65 wa-la-qad ʿalimtum "and verily you already know".

It can also occur before qad + perfect. Q2:65 wa-la-qad ʿalimtum "and verily you already know".

But if la- is really "verily, certainly"... you'd think it could just combine it with a regular verb as well right? Surely you can be sure about things that are happening in the present, for example... but la- never introduces verb-initial sentences (that are not apodotic to law)

The only exception to this are cases is with the pseudo-verbs niʿma "how good!" or biʾsa "how bad!" which can, and usually are introduced by la- (e.g. Q37:75 fa-la-niʿma l-muǧībūna "How good [are we] responding!", also e.g. Q2:102 with biʾsa).

Noun-initial sentences, however, can be introduced by la-! But again we find them to be surprisingly limited. These are only *exclusively* nominal sentences where the predicate is an elative (i.e. an ʾafʿalu form).

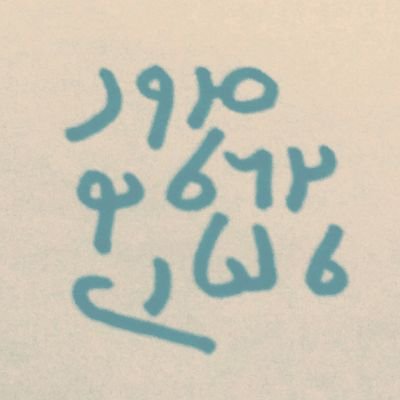

e.g.

Q12:8 la-yūsufu wa-ʾaḫūhu ʾaḥabbu ʾilā ʾabīnā minnā "Joseph and his brother are more beloved to our father than us"

Q12:57 wa-la-ʾaǧru l-ʾāḫirati ḫayrun li-llaḏīna ʾāmanū wa-kāna yattaqūna "the reward of the hereafter is better for those who believe and fear God"

Q12:8 la-yūsufu wa-ʾaḫūhu ʾaḥabbu ʾilā ʾabīnā minnā "Joseph and his brother are more beloved to our father than us"

Q12:57 wa-la-ʾaǧru l-ʾāḫirati ḫayrun li-llaḏīna ʾāmanū wa-kāna yattaqūna "the reward of the hereafter is better for those who believe and fear God"

Again, this distribution is rather odd. Why should you only be able to make an assertive nominal sentences when what you are asserting is that something is more-X than Y?

By now all of you are probably wondering why I haven't talked about the most common context for la- yet...

By now all of you are probably wondering why I haven't talked about the most common context for la- yet...

Those who know the Quranic probably know that la- *mostly* occurs in constructions introduced by ʾinna. What is odd with such constructions is that ʾinna seems to displace la- from its sentence initial position to a later position in the sentence

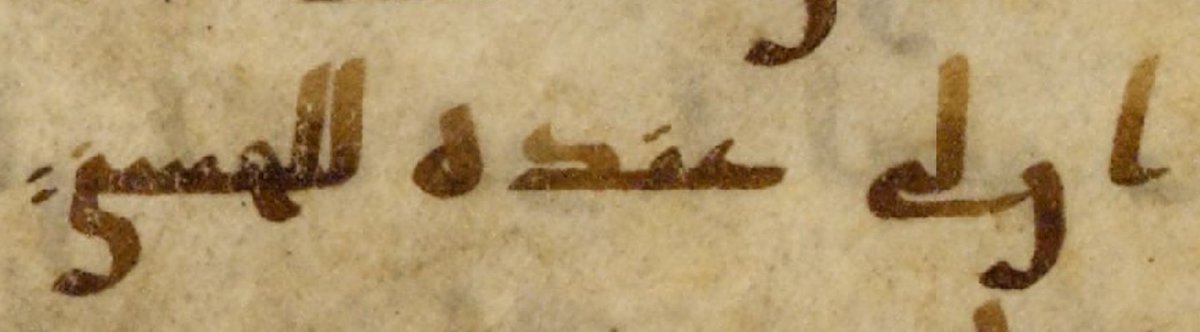

Usually this comes up as:

ʾinna SUBJECT la-PREDICATE

e.g. Q8:42 wa-ʾinna ḷḷāha la-samīʿun ʿalīmun

Nominal sentences introduced by ʾinna don't *need* to have la-:

Q49:1 ʾinna ḷḷāha samīʿun ʿalīmun

The "short" ʾinna (which doesn't take the accusative), ʾin works this way also

ʾinna SUBJECT la-PREDICATE

e.g. Q8:42 wa-ʾinna ḷḷāha la-samīʿun ʿalīmun

Nominal sentences introduced by ʾinna don't *need* to have la-:

Q49:1 ʾinna ḷḷāha samīʿun ʿalīmun

The "short" ʾinna (which doesn't take the accusative), ʾin works this way also

Q20:63 ʾin hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni "these two are sorcerers!"

ʾin may also precede verbs (mostly (only?) copula ones) in which case la- introduces the predicate as well

Q15:78 ʾin kāna ʾaṣḥābu l-ʾaykati la-ẓālimūna "the people of the thicket were wrongdoers"

ʾin may also precede verbs (mostly (only?) copula ones) in which case la- introduces the predicate as well

Q15:78 ʾin kāna ʾaṣḥābu l-ʾaykati la-ẓālimūna "the people of the thicket were wrongdoers"

la- can also occur on a finite verbal predicate after the subject introduced by ʾinna:

Q2:144 ʾinna llaḏīna ʾūtū l-kitāba la-yaʿlamūna ʾannahū … "INNA those who have been given the book LA-know that"

So la- just introduces the predicate after ʾinna right? Wrong!

Q2:144 ʾinna llaḏīna ʾūtū l-kitāba la-yaʿlamūna ʾannahū … "INNA those who have been given the book LA-know that"

So la- just introduces the predicate after ʾinna right? Wrong!

Many descriptions of Classical Arabic indeed say that la- is marks the predicate... But this does not work.

In existential clauses, the prepositional predicate obligatorily precedes the indefinite subject, appearing between ʾinna and the subject.

In existential clauses, the prepositional predicate obligatorily precedes the indefinite subject, appearing between ʾinna and the subject.

When this happens, la- is placed not on the predicate, but on the subject instead. This subject *still* receives the accusative of ʾinna in such a construction, so we can't start haggling over what really is the subject and what is the predicate in such cases:

Q2:248 ʾinna fī ḏālika la-ʾāyatan lakum "in that there is a sign for you"

It is also not the case that prepositional phrases cannot take la- and therefore the order is reversed or something like that. In non-existential clauses prepositional predicates take la-:

It is also not the case that prepositional phrases cannot take la- and therefore the order is reversed or something like that. In non-existential clauses prepositional predicates take la-:

Q2:176 wa-ʾinna llaḏīna ḫtalafū fī l-kitābi la-fī šiqāqin baʿīdin "INNA those who differ over the Book are LA-in extreme opposition"

It is possible in Quranic Arabic to have the 'inna [Prepositional predicate] la-[subject] order even when the sentence is non-existential. This is a marked word order, and seems to accommodate rhyme, but in such cases it is again the subject, not the predicate that has la-

Q92:12 ʾinna ʿalaynā la-l-hudā "INNA upon Us is LA-the guidance"

Q92:13 ʾinna lanā la-l-ʾāḫirata l-ʾūlā "INNA to Us (belongs) LA-the hereafter and the first life"

So what determines where the la- goes? It's not "on the predicate".

Q92:13 ʾinna lanā la-l-ʾāḫirata l-ʾūlā "INNA to Us (belongs) LA-the hereafter and the first life"

So what determines where the la- goes? It's not "on the predicate".

Is the rule "first phrase that does not follow ʾinna" then?

No, it's not that either. In sentences with adverbs (either single word adverbs or adverbial prepositional phrases) la- skips over them and lands on the predicate or subject that follows.

No, it's not that either. In sentences with adverbs (either single word adverbs or adverbial prepositional phrases) la- skips over them and lands on the predicate or subject that follows.

e.g.

ʾinna adv PREP-PRED la-SUBJ

Q41:50 ʾinna lī ʿindahū la-l-ḥusnā "INNA ---for me--- with Him will be LA-the best"

ʾinna SUBJ adv la-PRED

Q2:143 ʾinna ḷḷāha bi-n-nāsi la-raʾūfun raḥīmun "INNA God is -- for the people --- LA-compassionate and merciful"

ʾinna adv PREP-PRED la-SUBJ

Q41:50 ʾinna lī ʿindahū la-l-ḥusnā "INNA ---for me--- with Him will be LA-the best"

ʾinna SUBJ adv la-PRED

Q2:143 ʾinna ḷḷāha bi-n-nāsi la-raʾūfun raḥīmun "INNA God is -- for the people --- LA-compassionate and merciful"

It's not hard to describe what we see, of course. But it's pretty complicated to write a single description that correctly predicts where the la- ends up that accounts for multiple of these, clearly closely related, constructions at once..

Loading suggestions...