184) Everything that was doomed, tragic, wrong about the U.S. invasion of Iraq became apparent in the days before the statue of Saddam Hussein was toppled in Firdos Square. On April 6, 2003, the Marines who would tear down the statue arrived at the Diyala Canal outside Baghdad.

186) The bridge at the Diyala Canal was about 9 miles from the center of Baghdad. When McCoy's battalion approached the bridge, Iraqi soldiers shot at the Americans with RPGs and small weapons. I got into an open-backed Humvee that drove toward the fighting.

188) The Humvee was fired on, and fired back. "I shot him! I shot him!" a Marine yelled next to me. We jumped a curb, jarring everyone. "Who the fuck is driving?" another Marine shouted, as the shooting continued. "You're never going to drive this fucking Humvee again."

191) The Humvee got to the frontline. I spotted Col. McCoy, the battalion commander, and made a beeline for him. He was casual. "How are you doing, Peter?" he asked. McCoy had fought in the Persian Gulf War of 1990-1991. I told him I was fine.

193) Around us, war. The booms and whizzes of mortars, bullets, artillery. The midday twilight of a battlefield in smoke. Broken glass on the ground, chunks of concrete, civilians running for their lives, hands up. It was a day for connoisseurs of urban combat.

196) At the bridge, McCoy updated his regimental commander on his radio phone. "Dark Side Six, Ripper Six," he said, using their call signs. "We're killing them like it's going out of style. They keep reinforcing, these Republican Guards, and we're killing them as they show up."

197) McCoy was satisfied. "Lordy," he told me. "Heck of a day. Good kills." The next day, the battalion would storm the bridge and take the other side, killing civilians along the way. I don't think anyone involved will ever forget what they did, what they saw. Tomorrow, hell.

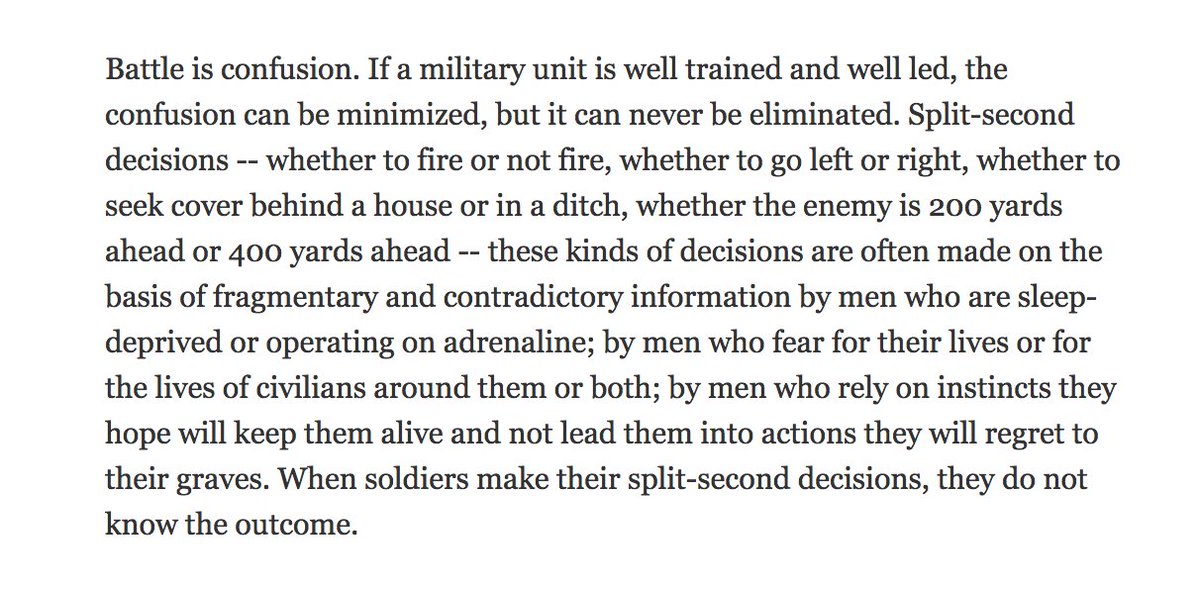

199) What Americans remember about the invasion of Iraq is what they choose to remember. Same is true for all our wars -- we choose what to remember. First is what happened to our soldiers. I get that. What happened to civilians --not remembered so much.

200) I would argue for thinking a lot more about the millions of civilians who are killed, injured, made homeless, traumatized for life by our wars. That's where the greatest suffering & heroism can be found. Far more civilians are affected by war these days than soldiers.

201) McCoy's battalion is remembered for its famous toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad. But before that -- on April 7, 2003, fifteen years ago today -- it stormed a bridge on the Diyala Canal outside Baghdad and killed civilians. That's what I remember most.

204) These casualties affected the battalion. In war, there's little more dangerous than a unit of soldiers who just lost their own; they are determined it won't happen again. (A side note: the shell that killed those Marines may have been an errant one fired by U.S. forces).

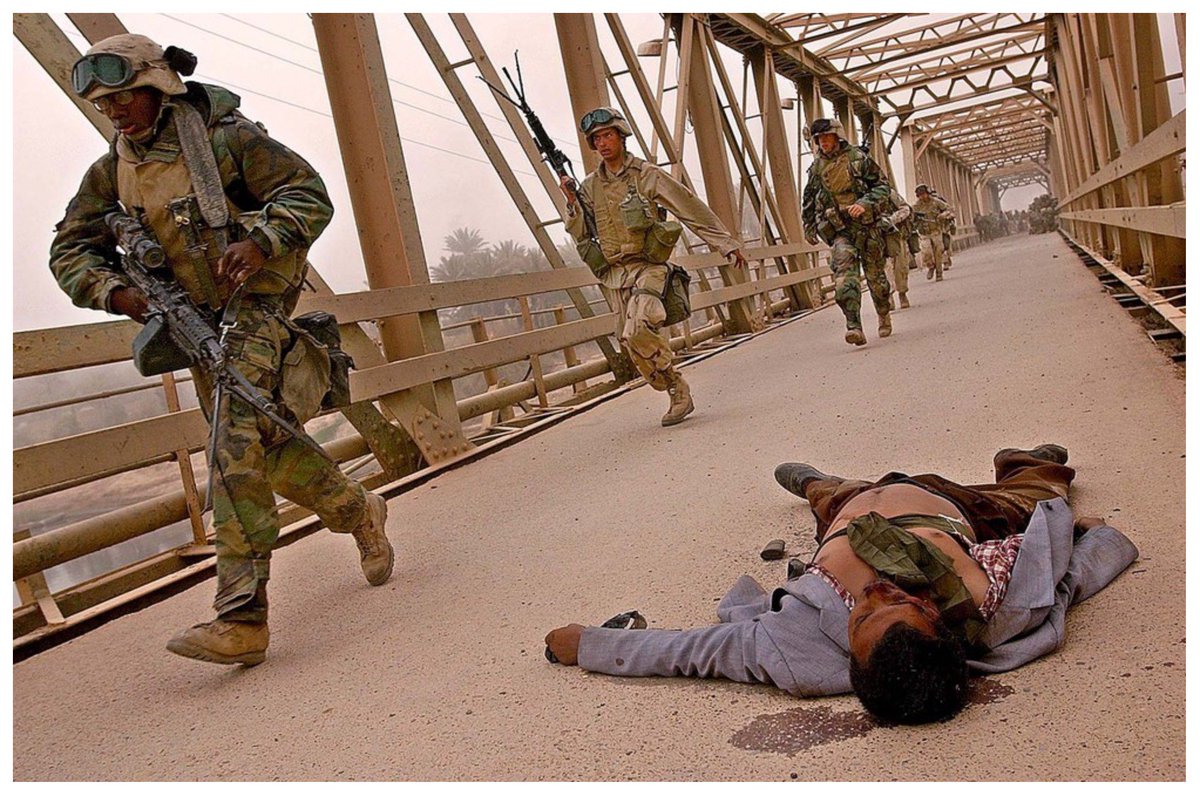

206) I joined a platoon that was about to cross. First they had to pass the wreckage of the shelled APC, still smoldering. "Holy shit," one of the Marines said. "Don't look, don't look," urged another. We ran across the bridge, past the body I mentioned earlier.

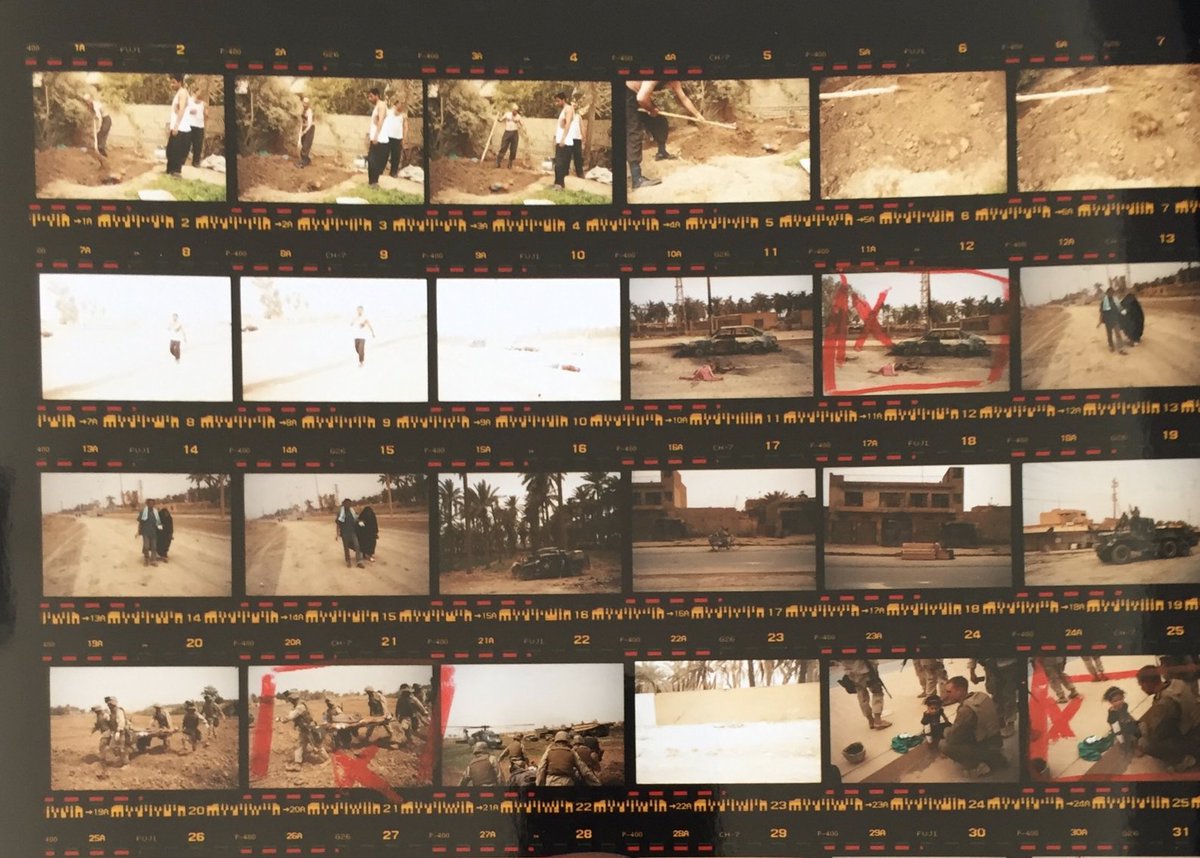

207) I have to warn you, the tweets that are coming will include some graphic photographs. There's a saying that only the dead have seen the end of war. I think that by seeing the dead of war, we can better understand what war really does, not in the abstract.

209) As soon as I reached the Baghdad side of the bridge, I noticed Col. McCoy, who was standing by an abandoned house with his radioman. "How are you doing, Peter?" he asked again. I stayed by his side for the rest of the battle.

212) A Marine ran up to McCoy and said Iraqi reinforcements had just arrived.

"A technical vehicle dropped off some assholes over there," the Marine said, pointing up the road.

"Did you get it?" McCoy asked.

"Yeah."

"The assholes?"

"Some of them. Some ran away."

"A technical vehicle dropped off some assholes over there," the Marine said, pointing up the road.

"Did you get it?" McCoy asked.

"Yeah."

"The assholes?"

"Some of them. Some ran away."

213) A few moments later, McCoy said to me, "Boys are doing good. Brute force is going to prevail today." He was listening to his radiophone. "Suicide bombers headed for the bridge?" he said into the phone. "We'll drill them."

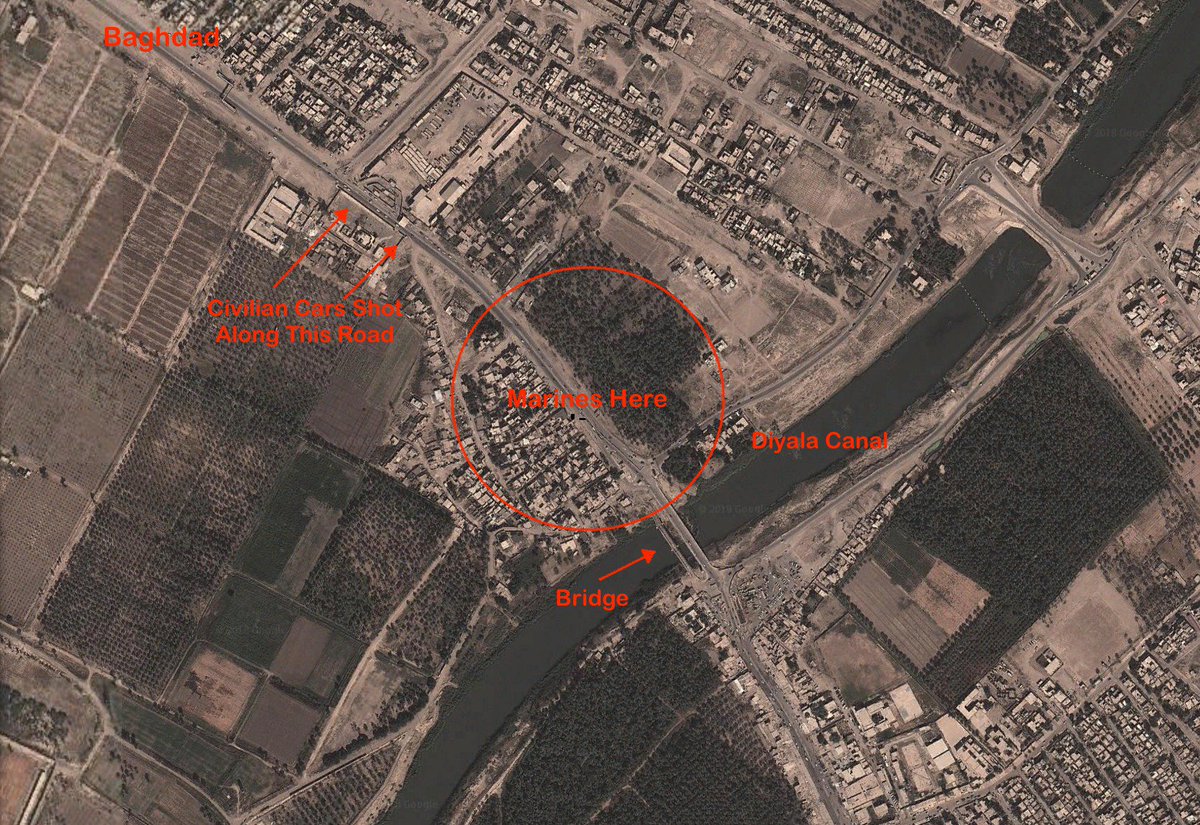

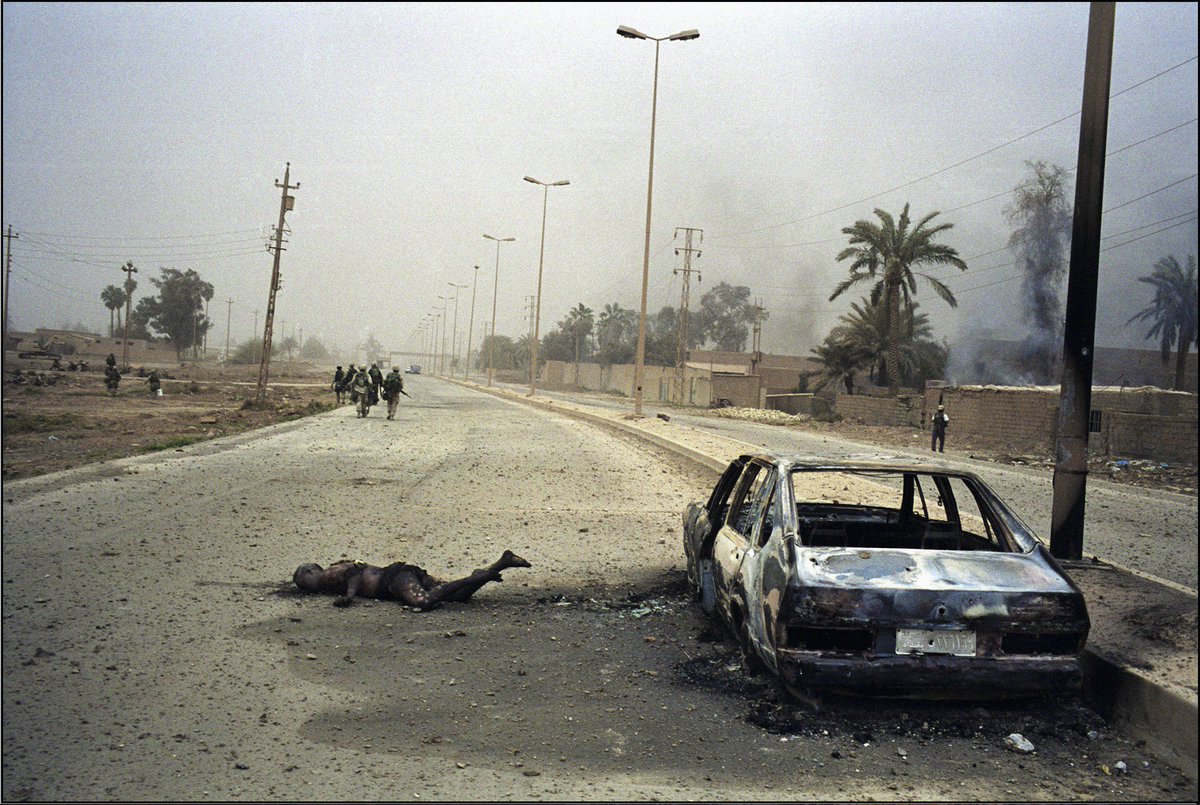

215) The plan was for snipers to fire warning shots in front of vehicles or at their tires, engine blocks. If they kept coming, they'd get drilled. It was an ineffective plan. How would civilians (unschooled in ballistics) know where shots came from, that they should turn around?

216) The Marines were basically invisible. They wore camouflage and lay on the ground. Their Humvees and tanks were on the other side of the damaged bridge. Iraqi civilians who were just trying to escape the American bombing of their city saw open road ahead of them.

217) The flawed plan broke down. As soon as snipers fired, other Marines opened up with their M-16s and machine guns. Gary Knight heard an officer shout "Ceasefire! Wait for the snipers!" Kit Roane heard a medic scream, "What are you guys doing out here?" But it was too late.

223) I may have posted too many of these gruesome photos; I don't know. A few days ago I wrote about the dilemma of not knowing how much to write about war, that sometimes you write too much, too intimately, too graphically. It's hard to know. But the killing isn't even over.

225) The next day would in some ways be more horrific; children would get badly hurt as these Marines moved closer to Baghdad's center. On the next day I would talk with Iraqis who survived the shootings on the road -- and I would talk with the Marines who were the shooters.

226) A bizarre coda to the day: after the battle, I relieved myself behind a bush. I was wearing a dark t-shirt & a jumpy Marine saw me and thought I might be an Iraqi fighter; he radioed for orders on whether to shoot me. Gary overheard it & said no, don't shoot, it's Peter.

229) For a few hours before disaster struck again, I was able to talk with survivors who emerged from the previous day's fusillade, and with Marines who fiercely defended what they had done.

230) Three people had been killed in the blue van but two survived, slightly injured, and I found one of them at a medic station. The battalion had an interpreter and I dragged him over to talk with her.

231) Her name was Emam Alshamnery (the spelling the interpreter gave me) and her toe had been shot off. She passed out when it happened and crawled out of the van in the morning with her husband, who also survived, injured.

232) She said the dead woman in the chador whom I had seen in the back of the van was her sister. The dead men in the front were relatives. They were just trying to get out of the city. Bags in the van were filled with food for the journey.

233) There was another survivor at the aid station, her name was Bakis Obeid (spelling from the interpreter). She told me she was in another car that was trying to escape Baghdad and had been machine-gunned by the Marines. She was dazed and said, "I lost my son and husband."

235) I don't know what happened to him or how it happened. I don't know his name. I don't know whether anyone who knew him was aware that he died on that road in this way on that day. No idea.

236) Along the road, not far from the blue van, three men were digging a grave. One of them was Sabah Hassan, a hotel chef. He said he was in a car with three other men, fleeing Baghdad, when they were fired on. One passenger was killed; I think they were burying him.

237) I asked Sabah Hassan what he was feeling. "What can I say?" he replied. "I am afraid to say anything. I don't know what comes in the future. Please." He plunged his shovel back into the earth.

240) I walked on the road and talked with Marines. Though I think there was some regret in the battalion, I didn't hear it on the road. "I wish I had been here," said a Marine who hadn't been on the frontline. Another told me, "Marines just opened up. Better safe than sorry."

241) Gary Knight was on the road and said, loud enough for anyone in earshot, that these cars should not have been shot, the civilians should not have been killed. After he walked away, Lance Corporal Santiago Ventura began talking to me, in anger.

242) "How can you tell who's who?" he said sharply. "You get a soldier in a car with an AK-47 and civilians in the next car. How can you tell? You can't fucking tell." He paused. He was upset at the notion that the killings were not correct. So he kept talking, close to fury.

243) "One of these vans took out our tank," he said, referring to an attack against another battalion. "Car bomb. When we tell them they have to stop, they have to stop. We've got to be concerned about our safety ... You can't blame Marines for what happened. It's bullshit."

244) "What are you doing getting in a taxi in the middle of a fucking war zone? Have you seen the EPWs? Half of them look like civilians. I mean, I have sympathy and this breaks my heart, but you can't tell who's who. We've done more than enough to help these people."

245) Ventura was not yet done. "I don't think I have ever read about a war in which innocent people didn't die," he said. "Innocent people fucking die. There's nothing we can fucking do."

249) Things now moved quickly, I may not be remembering the sequence precisely, but we (the unembedded journalists) were at a house on the road at midday and heard a fighter jet swoop overhead and a large explosion suddenly rocked us; a bomb hit very close. We left, fast.

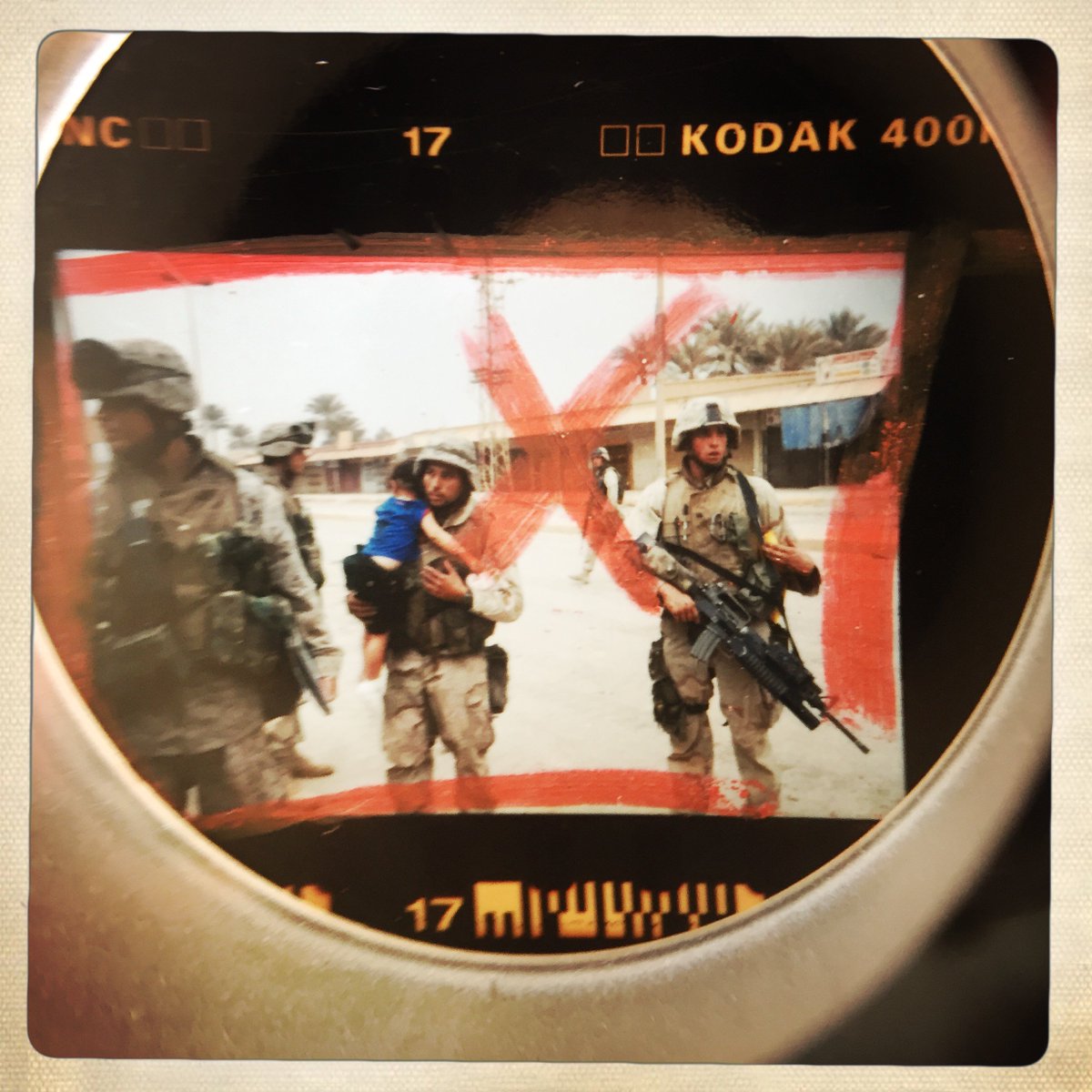

250) An Iraqi girl had been injured and the Marines had her. Enrico Dagnino, the photographer, saw an Iraqi man waving at them, holding up the body of a boy who was injured, too. The Marines handed the girl to Enrico and got the boy.

251) Enrico, holding the girl, jumped into the front seat of Laurent's SUV. The father and injured son got into the back. They tried to drive to the rear but got shot at by Marines, so they turned back to the frontline, which was safer.

252) They needed an escort to the rear, so a Marine tank-recovery vehicle -- the one that a day later would tear down the statue of Saddam Hussein -- drove ahead of them to ensure other Marines wouldn't open fire. The area was a free-fire zone on vehicles that weren't American.

255) I have no idea what happened to these children. If they survived Iraq's many years of warfare, they would be in their late teens or twenties now. What have their lives been like? The possibilities are not good. Imagine the trauma of this day, add 15 years.

256) There was a lull in the chaos. I sat in my SUV and wrote. A few dozen yards away, there was a bullet-riddled car with a corpse or two. I don't remember being too bothered by it. I just wrote.

257) The day wasn't over yet.

258) The battalion moved forward, closer to the center of Baghdad. There hadn't been any ground fighting in this area and there wasn't any resistance, as there had been at the Diyala Canal. There was just looting, everywhere.

262) I spent the night in the courtyard of a technical college six miles from Baghdad's center. Marines shut the gates to keep out Iraqis who were pleading to get inside. "I am working on my Ph.D," a polite Iraqi told a sentry in excellent English. "I need a computer."

263) As I went to sleep in my SUV, I expected the next day would be far more violent than the Diyala Canal, because we would penetrate into the heart of Baghdad. I would be wrong about the violence but what happened would be historic and insane.

266) In addition to being at Firdos Square -- during the invasion I followed the Marines who would tear down the statue -- I have done follow-up interviews with nearly everyone involved, Marines and journalists. I've written about it elsewhere but not in the way I hope to here.

267) The toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein was not what it seemed to be.

269) The Marines and journalists following them -- all of us expected a lot of fighting. But in the morning, Laurent Van der Stockt, the photographer I was working with, talked on his satphone with a French journalist at the Palestine Hotel, Remy Ourdan, who had surprising news.

270) Laurent, on his satphone, approached Col. McCoy. "Colonel, my friend at the Palestine Hotel is saying there is nobody in front of us -- the city is empty," Laurent said. McCoy nodded but replied that his Marines wouldn't get to the center so fast; there would be resistance.

271) Laurent told Remy that they probably wouldn't be seeing each other that day. "But tell the colonel that Baghdad has fallen," Ourdan replied. "There is no more resistance. The city is open."

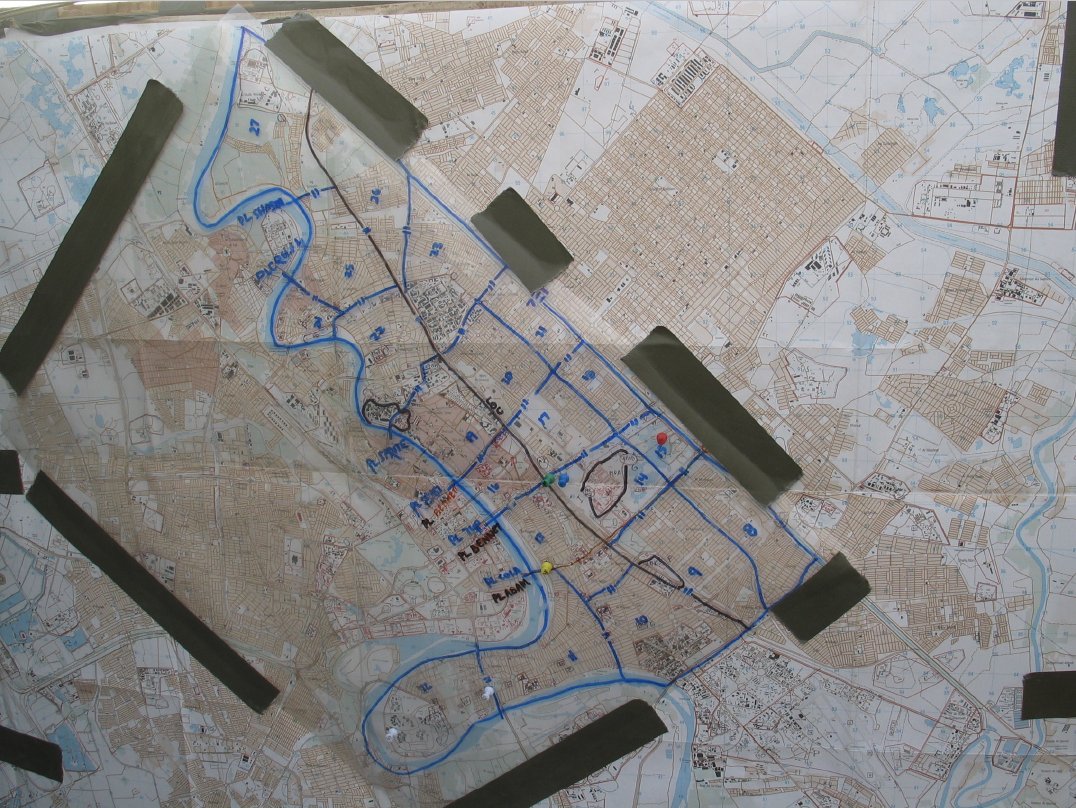

275) The planners in McCoy's regiment tasked his battalion with capturing the central zones of Baghdad. One of the planners, Major John Schaar, later told me McCoy's battalion was chosen because "they were the sharp guys" -- the ones who had fought the most in the invasion.

277) Around midday, the battalion slowly and cautiously headed into Baghdad, its tanks leading the way. M-16s were pointed out the windows of pretty much every Humvee. The worst was expected -- but didn't happen. Some Iraqis on the streets waved.

278) Simon Robinson, a Time reporter embedded in McCoy's Humvee, heard Marines report on its radio that Iraqis were offering them tea. "We're not getting resistance, we're getting cakes," McCoy remarked.

279) About a mile from the center, McCoy got an order from his regimental commander, Col. Steve Hummer, who told him to secure the Palestine Hotel. Robinson, in the back, leaned forward to remind McCoy that journalists were there. McCoy, an unusual officer, liked journalists.

280) McCoy already knew of the Palestine -- journalists following his battalion had previously mentioned to him that their colleagues were there, in jeopardy. In the Humvee, Robinson saw a satisfied expression spread over McCoy's face. He was going to free the media from Saddam.

281) What happened in the next few hours was a crazy sequence of events. The toppling and all its theatrics were the product of chaos, opportunism, improvisation, and manipulation.

283) McCoy stopped his Humvee a mile away to study his map and figure out the way ahead. A few journalists who had ventured outside the hotel happened to find McCoy. "Where is this damn Palestine Hotel?" McCoy asked one of them -- coincidentally, it was Remy Ourdan.

284) I was a few dozen yards away and saw a flurry of movement around McCoy. "I'm going to the Palestine Hotel!" he shouted as he got into his Humvee. I jumped into my SUV and followed.

285) Ahead a bit, at the very front of the battalion, Capt. Bryan Lewis, who commanded the tanks, was also unsure where to go. He saw a car with "TV" scrawled on its side and yelled from his turret, "Is this the way to the Palestine?"

286) Markus Matzel, a photojournalist from the hotel, pointed down the road. Capt. Lewis motioned for Matzel to come along, in case further directions were needed. Matzel hopped onto the turret and led the Marine Corps to Firdos Square.

289) Firdos was a bubble -- fighting & looting continued elsewhere -- but the bubble is pretty much all that the rest of the world saw. TV coverage from Firdos was nonstop and, especially in the U.S., filled with enthusiasm for what was portrayed as Iraq's thrilling liberation.

290) The statue of Saddam Hussein was at the bubble's center. Its toppling was not part of a master propaganda plan by the Pentagon, however. The idea for tearing it down was first expressed by a gunnery sergeant, Leon Lambert, as his tank-recovery vehicle rolled into Firdos.

291) "Hey, get a look at that statue," Lambert radioed to his commander, Capt. Lewis. "Why don't we take it down?" Lewis said no -- he didn't want to get distracted as they secured the square.

293) A handful of Iraqis walked into the square, a dozen or two. Lambert, in his T-88 tank-recovery vehicle, got on the radio again. "If a sledgehammer and rope fell of the 88, would you mind?" he asked Lewis. This time, Lewis replied, "I wouldn't mind. But don't use the 88."

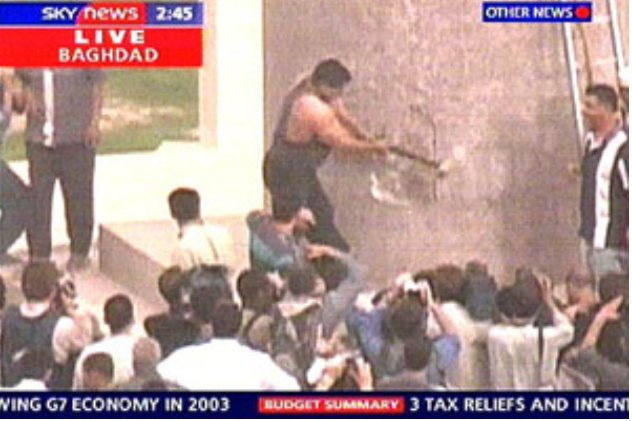

295) Notice the photographers at the bottom of the frame. Their presence and interest directly influenced what the Iraqis did to the statue. A famous media study from 1953 by Kurt and Gladys Lang made this point -- cameras provoke people to do things they wouldn't otherwise do.

296) There was a period of excited sledge-hammering but gradually the photographers drifted away -- they had gotten their shots. The hammering ceased soon after. Lambert's rope, thrown around the statue's neck, ceased to be of interest, too -- it couldn't bring down the statue.

298) McCoy understood publicity. "You've got all the press out there and everybody is liquored up on the moment," he said. "You have this Paris 1944 feel. I remember thinking 'The media is watching the Iraqis trying to topple this icon of Saddam Hussein - let's give them a hand."

298) Capt. Lewis walked over and asked whether his men should finish the job. McCoy radioed his regimental commander, Col. Steven Hummer. I later talked with Hummer, who explained that he had no idea what was happening at Firdos -- at his field headquarters, he didn't have a TV.

299) "I get this call from Bryan," Hummer told me, "and he says, 'Hey, we've got these Iraqis over here with a bunch of ropes trying to pull down this very large statue of Saddam Hussein (and) they're asking us to pull it down.' So I said O.K, go ahead."

300) McCoy got off the radiophone with Hummer and told Capt. Lewis, "Do it."

303) Notice how people are walking toward the T-88 and the statue. The T-88 was drawing them there.

305) In the 1960s, historian Daniel Boorstin identified a category of media spectacle that he called "pseudo-events," which are created to be reported on. I think the toppling of the Saddam statue belongs in that category. Too often, we journalists go along with these things.

309) At Firdos Square, a war narrative of joyous liberation was getting the pictures it required. This episode demonstrated a media theory, or more broadly put, a truth of human nature, that has been around for a long time, that entraps us still.

310) War myths are created. As Walter Lippmann wrote, they emerge from "the casual fact, the creative imagination, the will to believe...Men respond as powerfully to fictions as they do to realities, and in many cases they help to create the very fictions to which they respond."

311) At CNN's control room in Atlanta, producer Wilson Suratt was in charge on April 9. "The climax ... was going to be the troops coming into Firdos Square," he later told me. "There wasn't going to be a surrender. So what we were looking for was some sort of culminating event."

312) Suratt's comments help explain why CNN and other networks had non-stop coverage from Firdos, ignoring the fighting and looting elsewhere in Baghdad. Everyone seemed to want a culminating event (a myth, perhaps). Late in the afternoon, Corporal Edward Chin provided a hand.

314) The flag would become deeply controversial. It was popular in the United States but unpopular elsewhere, a sign of U.S. domination of Iraq. How and why did this seminal and divisive moment happen? The bizarre truth: it was a spur-of-the moment improvisation by a few Marines.

318) Where did the flag come from, how did it get into Chin's hands and atop the statue? The flag belonged to Lt. Tim McLaughlin, who led one of the tank platoons. I wrote a lot about him earlier in this thread, because he kept a diary that described the violence of the invasion.

320) During the invasion, McLaughlin had tried to raise the flag -- he wanted a picture of it flying in Iraq. One time, there was too much shooting going on. Another time, a tank rolled over the flagpole he was going to use. His failed efforts became a joke in his tank company.

321) After Col. McCoy gave Capt. Lewis a green light to tear down the statue, Lewis told McLaughlin to get his flag -- his chance had come. The flag was handed from Marine to Marine until it got to Chin and covered Saddam's face.

322) This triggered another famous moment that was also the result of improvisation. I've written before in this thread that war is chaos -- and the events at Firdos are no exception. Whether it's fighting or flags, much of what happens in warfare is unplanned, ad-hoc.

323) McCoy, too busy to keep an eye on the statue, didn't see the flag go up. Once he noticed, his first thought was "Oh shit." He ordered it taken down. Alarms were everywhere. His commander, Col. Hummer, received an order from *his* commander, Gen. James Mattis, to get it down.

325) This politically-astute maneuver wasn't directed by the Pentagon. A lieutenant in the battalion, Casey Kuhlman, got an Iraqi flag during the invasion and realized, when the American one went up, that it was a bad idea. So he handed his flag through the crowd, and up it went.

Loading suggestions...